Cinematographer Rachel Morrison Clarifies “Mudbound”-Spotlight on the 55th New York Film Festival

By Laura Blum

“I dreamed in brown,” says Laura McAllan (Carey Mulligan) of the grime that permeates rural life in Mudbound. Her lament gave cinematographer Rachel Morrison a departure point for evoking Dee Rees’ WWII-era drama set in the Mississippi Delta. Much of what we see in the film, from fields and farmhouses to instincts and mores, comes from the sodden muck.

Adapted from Hillary Jordan’s 2008 novel, Mudbound is a tale of two families, one black and one white, both struggling to make ends meet in the Jim Crow South. The story opens at the end, with Laura’s husband Henry McAllan (Jason Clarke) and younger brother-in-law Jamie (Garrett Hedlund) digging a grave for their father, Pappy (Jonathan Banks), in a torrential downpour. Why Jamie imagines his brother leaving him to drown in the hole is as mysterious as the reticence their black neighbors show when asked to help with the coffin. Rewind a few years back, as Henry is wooing 31-year-old virgin Laura back in her native Memphis. What he lacks of Jamie’s romantic charm, he makes up for in seeming solidity. Laura says yes, and the pair winds up on a godforsaken Mississippi farm with irascible bigot Pappy while Jamie goes off to fly bombers against Nazi Germany.

The black neighbors turn out to be the Jackson family, sharecroppers who lease and work part of the McAllan’s land at a nominal remove from slavery. Their eldest son Ronsel (Jason Mitchell) joins the 761st Tank Battalion under General Patton, leaving preacher-farmer Hap (Rob Morgan) and his deft wife Florence Jackson (Mary J. Blige) to pray for his safe return. Return he does, just like Jamie, and the two veterans forge a bond.

If only things weren’t so mudbound. The respect Sergeant Ronsel Jackson experienced overseas while fighting against fascism hardly obtains back home, and his newly emboldened behavior rubs the white supremacist townsmen the wrong way. For Jamie’s part, the small town suffocation not only plunges him further into PTSD and booze, but his assumed trackrecord of wartime killing threatens Pappy’s machismo. As the brothers-in-arms share their disillusionments and dreams, their friendship further inflames local passions and cocks the film to its explosive climax.

“One of the film’s themes is hope and reality,” says Morrison, who holds an MFA in Cinematography from the American Film Institute. Her visualization of Ryan Coogler’s Fruitvale Station contributed to that film’s rapturous reception at Sundance, where it nabbed a Grand Jury Prize and the Audience Award. It also thrust Morrison into the limelight and led to a flurry of projects including Cake, Daniel Barnz’s portrait of disability starring Jennifer Aniston; Sara Colangelo’s Little Accidents, set in an Appalachian mining town; and Rick Famuyiwa’s spikey coming-of-ager Dope. The Cambridge, MA native has also shot for television, with outlets ranging from HBO and Showtime to ABC and CBS, and in 2014 she made her directorial debut with John Ridley's show “American Crime.”

Morrison called thalo.com from Atlanta (where she’s completing pick-up shots for Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther) to muse over Mudbound--her 14th feature in a slate that’s garnered the 39-year-old DP a Kodak Vision Award, inclusion in Indiewire’s shortlist of cinematographers to watch and two Emmy nominations.

thalo.com: So how did Laura McAllan’s comment about brown influence your work?

Rachel Morrison: More in the tactile quality, wanting nothing to feel pristine. The idea that mud was caking everything made me think about creating a perceivable grain. I wanted it to feel a little bit gritty, a little dirty, a little muddy, but not from a color point of view. There’s a tendency for brown and sepia tones to be people’s go-to for a vintage look. I really didn’t want to fall into the cliché of, Tea stain means old.

th: To what extent did Hillary Jordan’s novel inform your work?

RM: I read the book and then I read the initial screenplay, which Virgil Williams wrote and then Dee did a pass on. By the time we shot the film, I’d say the book was a little less fresh in my memory, but some of the visual ideas that Dee had came from the book.

th: What were some of the themes Rees stressed?

RM: We both believe in a subjective naturalism. I think that’s a big reason I was chosen for the job. So it was authenticity above all else. We used very minimal makeup and we didn’t want anything to be too stylized.

th: Were there any particular photographers, artists or filmmakers whose work inspired the look of Mudbound?

RM: My background is in still photography, so my first thought when Dee approached me about the film was the Farm Security Administration photographers. They’ve been an influence of mine since the beginning, so it was nice to be able do a piece where I could honor their legacy. Specifically, I was referencing the (FSA Depression-era photojournalism) of Dorothea Lange, Gordon Parks, Arthur Rothstein and Ben Shahn.

th: What were some of Dee Rees’ visual references?

RM: One of her first references was Les Blank, the documentary filmmaker, which I thought was so interesting because people rarely reference documentarians for narrative films. She was taken with his use of camera and the sense of a very fluid, subjective authenticity. Dee also introduced me to the work of artist Whitfield Lovell, specifically some of his portraiture on wood. When you look at the Jackson’s home, with all the textures and warmth that can come from wood, you can feel the layering and texturing.

th: Did Rees have any photographers in mind?

RM: She referenced Robert Frank, both for the idea of the American Dream and for the compositions--frames that were either bursting at the seams or completely isolationist.

A commonality among the characters is the hope for a share of the American Dream and the hope for something greater and bigger than they are. There’s the idea of conquering the land versus the reality of nature and the elements, which are so much stronger than any one human or even a group.

th: Is that partly what informed your striking mix of close-ups and sweeping landscapes?

RM: With the more personal shots, there’s the idea that humanity is what bonds us all and that love can be stronger than anything. So we wanted to capture the moments at home and the intimate moments between people. The widescreen shots gave us the ability to contrast a small figure against a massive amount of landscape, and what that meant both in terms of hope and of having one’s dreams quashed.

th: With the widescreen shots, were you consciously going for the look of a Western film?

RM: I suppose on some level. When I think of Farm Security Administration photography and I think of Westerns, there’s certainly a lot in common. You have these structures that are in a widescreen frame, and the structure becomes quite small and there’s a feeling of vastness that surrounds it.

th: What was behind the different lighting and tones of the McAllan’s home versus the Jackson’s?

RM: One of the literal differences was that the McAllans had electricity and the Jacksons didn’t. So when it comes to night scenes, there’s a separation there, although the McAllans’ electricity was always on the fritz and was never entirely attainable either. But about the look, as we said, there were warm, earthy wood tones in the Jackson’s home. They didn’t have windows. The window treatments were homemade and were a sort of muslin cloth. So there’s a real rich warmth to the scenes in the Jackson home--not particularly colorful, but warm in hue, whereas the McAllan household has more apparent colors and color separation. And yet, the colors are somewhat desaturated or pastel and nothing feels new. That’s part of the caked-in-mud theme where everything has a layer of soot on top of it. As far as contrast goes, with the McAllans the contrast was always a little bit higher. That’s because the stakes between husband and wife, husband and employee were always on the brink. Home was a threat for Laura McAllan, whereas with the Jacksons there’s this firm foundation of love and support, and the home was a safe place for them.

th: One of the lightest moments is the first time we see the Jacksons in their makeshift church. Talk a little about this.

RM: A lot of the beauty and strength and hope for the Jacksons comes from the church and prayer and belief in something greater than themselves. It is a light place for Hop. It’s where everybody comes together and wears their best clothes and it’s a break from the toils of the land. We wanted it to feel as pristine as anything on the farm.

th: The scene with Laura framed against a sunset stands out as much for its beauty as for the fact that she too is catching a rare break from drudgery, however relatively privileged that may be.

RM: We didn’t want it to feel like a Terrance Malick film. It wasn’t about how beautiful things always are. It was about contrasting the beauty that begets hope with the reality that is the top-down, middle-of-the-day beating sun. The DP in me would love to shoot everything in magic hour, but that wasn’t the story. It’s just beautiful enough to keep you coming back for more, but the next day the reality sets in.

th: And so does the rain.

RM: The elements were something else on this one! One of my favorite photos from the set is a rain tower in the rain. Any time you need rain you get sun! For the first time in my history of shooting movies, we had a reverse cover set. So when we knew it was going to rain, we had the grave digging scene where we needed some wide shots with real rain. But as you get in tighter it’s all rain towers.

th: Before Pappy got deep-sixed, how did you wield your camera to tease out any nuance in him?

RM: I tried to find moments where Pappy is playing with the grand daughters to show there’s a human side as well.

th: Conversely, the Jacksons come off as almost idealized. What directions did you get from Rees here?

RM: A lot of the film was informed by Dee’s grandmother’s diary. She had these amazing journals that she shared with the cast and with us. To the extent that the Jacksons were representative of her real family, they were treated with real love and kindness.

th: In this film different characters get a crack at telling their story. How did you handle the almost Faulkneresque shifting narratives?

TM: Dee and I decided early on that we would start the movie fluid, while each of the character’s lives is not in tumult or disarray. For Laura it was when she lived a cultured urban life, and then the McAllan’s life starts to fall apart when they get to the farm. So we switched to handheld at the moment they arrived at the new house. For the Jacksons, their life was sort of smooth until interrupted by the McAllans. So for them we were fluid until that point, and then we switched to handheld.

th: You’re especially known for your handheld POV camerawork on Fruitvale Station. What do you like about it?

RM: The thing that I love about handheld is that you can attenuate it. With fluid camera movement, it’s just fluid. But with handheld you can shoot something at a one or at a 10 in terms of the level of “handheldness,” for lack of a better word. Whether it’s the contrast of the lighting or the handheldness, it’s always a reflection of the stakes in that moment. The nice thing about handheld is that you can say, This is a three; or, This is a nine. But for the most part, we were trying not to be noticed. ISo there was sort of a fluid handheld as a jumping off point and then certain scenes where the stakes were heightened where we would bump it up a couple notches.

th: What were you shooting on?

RM: The Farm Security Administation lover in me feels kind of sacreligious that we didn’t end up shooting analogue. But had we shot on film, we would have lost two shooting days and we couldn’t afford to do it on this one. So we shot on the Alexa Mini with older anamorphic glass lenses for the bulk of it and spherical glass lenses for some of it. It was the anamorphic C’s & D’s, and the spherical PVintage Panavision rehoused Ultra Speed Prime and Super Speed lenses, both sets from the 60’s and 70’s predominantly. And we shot raw. I’m actually not of the belief that you have to shoot raw with the Alexa, but I think when you’re shooting this huge contrast variation between interior and exterior, it’s really helpful to have that extra latitude.

th: What are the challenges of filming and lighting scenes with both black and Caucasian characters?

RM: There’s always a challenge when you have two very different skin tones in the same frame. It’s about being sensitive to whoever’s skin tone is the more complicated and then working with that as a jumping off point. That isn’t universally the black person’s skin. So it’s about starting with who needs the most attention and working backwards from there. There have been a lot of articles lately about lighting dark skin. But I think it’s a gross generalization because probably even more than Caucasian people, there’s such a gradation of darker skin colors. I find that black skin reacts incredibly differently to light, so it can’t be generalized. For me it’s really about lighting skin in general and being sensitive to each character’s tonality and reflectivity. With darker skin, you’re dealing a little bit more with reflected light as well as with incidental light. Whether Caucasion or black, there are people for whom no amount of light is ever going to be absorbed; it’s always going to be reflected. And then there are other people who are practically like human bounce boards, and you have to take light away from their faces as opposed to trying to light them.

th: Is it an oversimplification to say that, with Mudbound as the latest example, you’re drawn to stories that crisscross class and race and are socially conscious?

RM: I would say socially conscious for sure. I never thought about it as class and race per se. I’m drawn to and compelled to have a message as well as to entertain. In this day and age, I don’t go to the movies purely for escape or just to be entertained. I like to be challenged and I like to challenge the audience as well. I’ve always been drawn to these films, but now more than ever even two hours of our time is so critical. We all get our messaging in various ways now, whether it’s Twitter or whatever. I’ve always thought it’s important to be socially conscious, but now the stakes have been raised, especially when it comes to reaching the millennial crowd and the next generation of people who will be the ones to make a difference. Cinema and media are one outlet we have.

th: What advice do you have for the next generation of cinematographers?

RM: My biggest advice is, Stay true to yourself and to the stories you want to tell. It can be really easy to get dissuaded from your own path. Shoot comedy and you’re going to get nothing but comedies. And that could be great: if you want to shoot comedies, you’re good to go. But the work begets more work like it, typically speaking, so the sooner you can find your voice and tell a story that’s meaningful to you, the sooner you’ll get work like that.

th: Since you also tend to operate your own camera, got any tips for camera operators?

RM: My advice to any camera operator is, Follow your instincts. Shoot from the heart and less from the head.

Photos:

- (L-R) Jason Mitchell as Ronsell Jackson and Garrett Hedlund as Jamie McAllan in “Mudbound.” Photo courtesy of Netflix.

- (L-R) Mary J. Blige as matriarch Florence Jackson and Rob Morgan as patriarch Hap Jackson in “Mudbound.” Photo courtesy of Netflix.

- Carey Mulligan as Laura McAllan in “Mudbound.” Photo courtesy of Netflix.

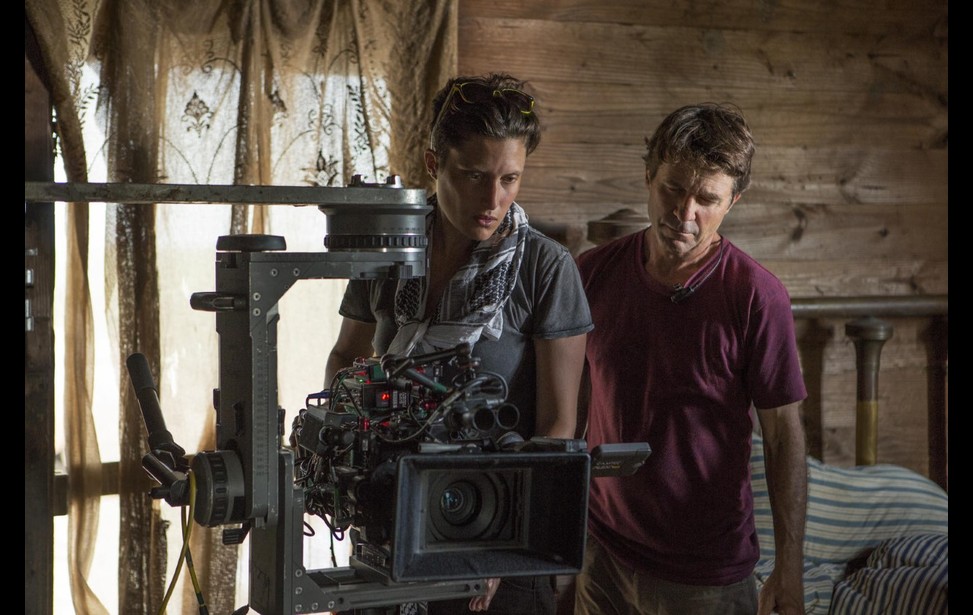

- Cinematographer Rachel Morrison with 1st AC Rob Baird on the set of "Mudbound." Photo by Steve Dietl courtesy of Netflix.