Production Designer Hannah Beachler Relives “Black Panther”

By Laura Blum

Been to Wakanda? Hannah Beachler has, and her production design for the fictional country at the heart of Black Panther proves that vibranium exists. How else to explain such a radiant spectacle if not daily doses of the African El Dorado’s magic metal?

The Marvel Studios actioner follows T’Challa (Chadwick Boseman) finding his way as Wakanda’s new warrior king and superhero Black Panther after the death of his father T’Chaka (Atandwa Kani). Presiding over unique reserves of vibranium – which have secretly fueled the Wakandan technological miracle -- T’Challa plans to continue his nation’s isolationist traditions. These haven’t always pleased everyone. In 1992, from his base in Oakland, California, T’Chaka’s war dog brother N’Jobu (Sterling K. Brown) smuggled out some of the energy-packing ore to help oppressed people (especially of color) ravaged by war, famine, poverty and other scourges. T’Chaka branded him a traitor and killed him. Now, a generation later, the sin of the father is visited on his children: N’Jobu’s son, Erik Killmonger (Michael B. Jordan), is bent on avenging his father’s murder and seizing T’Challa’s throne.

Rarely, if ever, has a blockbuster so seized the zeitgeist. Ryan Coogler’s film not only aces its brief as a superhero game-changer, it’s arguably a cultural watershed. Mass audiences can now swap their patronizing Hollywood images of “the dark continent” for a visceral experience that celebrates Africa’s vibrancy—and a utopian imagining of what might have been without colonization and the slave trade.

Asked what first came to mind when reading the script, Beacher tells thalo.com that she was most impressed by the intimate father-son story at its core. That may come as a surprise considering the production’s vast scale.

Nine months of research went into birthing Wakandan civilization before any building tools were taken up in Atlanta. First the filmmakers had to crack its origin myth. One of the biggest challenges was representing the diversity of Wakanda’s citizenry without resorting to stereotypes. Guided by Coogler – who had tapped her to create the look of Fruitvale Station and Creed – the Emmy-nominated designer (whose credits also include Miles Ahead and Lemonade) mapped out the tribes inhabiting the space. The question, “Where did everybody migrate from?” led the team into intensive soul-searching and a spree of pan-African borrowings.

thalo.com: “Who are you?” is a recurring line in the film. How did that question of identity influence your visual concept?

Hannah Beachler: Ryan and I talked a lot about what it means to be African. And my question was, How do I visually show that? – not really having a connection with the continent. So it was really important for me to go there. I found this connection that I can’t really explain, as if the things that I do suddenly made sense: This is part of my history, my heritage, my genes.

th: How did your trip impact your design thinking?

HB: When I was flying over Africa and looking down, a lot of it is farmland, and the way it was cut up looks like textiles. Pre-trans-Atlantic slave trade, the textile trade was huge in Africa. It was murdered after colonization. I wanted to pay homage to that and use a lot of pattern and color. But it was going to Blyde River Canyon at Three Rondavels in South Africa and having a guy tell me how the mountain structure looks like these giant Rondavel huts that got me really thinking outside the box. That shape made sense as to how to build. It was after that trip that I said, “How about if we put the Rondavel top on top of the skyscrapers?” Once I figured out the architectural reasoning for putting the Rondavel tops, that’s when the Golden City started taking a whole new form. The Golden City is the capital of Wakanda and where the first homes were.

th: How do the sets reflect character evolution?

HB: People think of Wakanda as the most technologically advanced place on the planet, but It was important to show the beginnings. That’s where Hall of Kings in Necropolis comes in. We went around a lot about whether we should put technology in the set. I was always like, “No, this is the one beat where we see where they have come from – their evolution.”

th: How did you blend the African past with Afrofuturism?

HB: A conflict that I had involved Golden City. I originally put old architectural buildings inside a giant encasement of glass. It felt like a living museum. I showed this to Ryan and looked at me and said, “They would touch their history. It would still be a part of their life. They wouldn’t put it behind glass.” That spurred me to think about how I could incorporate the idea of them touching and feeling their history. The birth, life, death cycle is the femine cycle.

th: Does the recurring circular motif reference reference the life cycle?

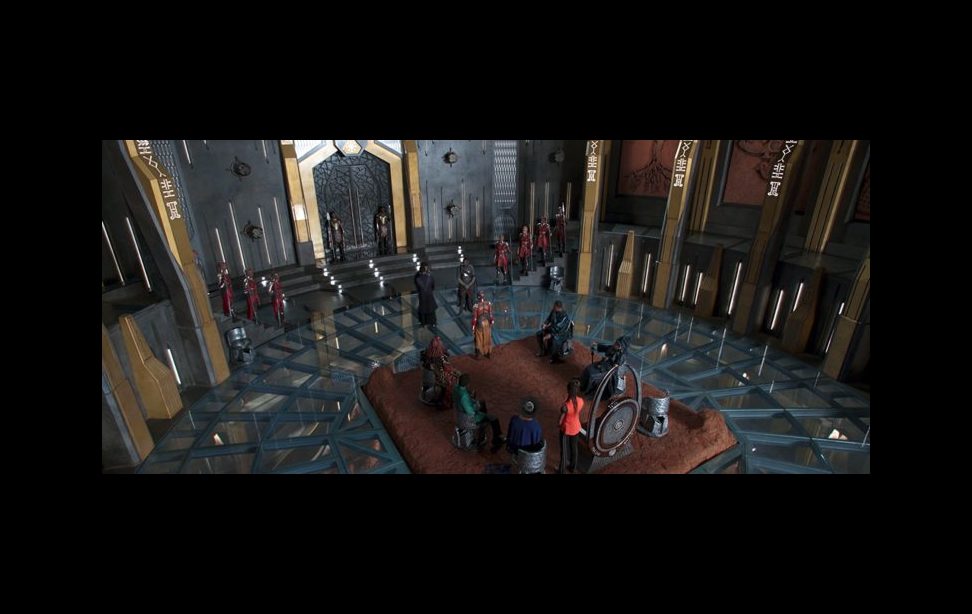

HB: Yes, which is why I say my designs are very feminine. You see the the circle in the Hall of Kings, which is very much in its natural state: It’s in the rainforest; it’s decaying; it has the heart-shaped herb. It’s a space that’s going through a natural process without high tech. The evolution of that is the Throne Room, which has the glass and the gold and they’re sitting on top of the Timbuktu Pyramid in the middle of that sacred ground where the elders are. Putting the old next to the new was about seeing the evolution of what is important to them traditionally.

th: Vibranium, water power, panther power, warrior power: How did you approach these and other visual metaphors of power?

HB: Ryan wrote the feminine characters very powerfully. Princess Shuri (Letitia Wright) is the smartest person on the planet. When you look at the designs that are more curvaceous, softer, more intimate, you’re feeling the power of the people who inhabit the spaces. It’s an example of design as storytelling. The circle within a circle is about energy, which is about the water system. That’s the one set besides the falls where you’ll see water. It evolves to the Throne Room. Yeah, there’s technology, but each tribe has a sijil in the background.

th: Break them down for us.

HB: The Water Tribe sijil on that wall is a horse because they’re master horsemen and they also have rhinos. The River Tribe sijil is a fish with a fish in its mouth, talking about replenishing the rivers and the Earth. They’re purveyers of the water. Then you have the Merchant Tribe, and their sijil is an African coin from the 14th century, which was sometimes wood, sometimes gold. The Jabari Tribe, which does not come to the Council meetings, but their sijil is a tree because they’re master woodsmen. We reference the Dogon Tribe and everything around them is wood. So their sijil is the tree with the roots that never meet the ground because they were uprooted from Wakanda. They worship Hanuman, the gorilla god, and the rest of Wakanda worships the Panther God Bast. You see that the Jabaris were isolated from their people. The King’s Guard has a sidgel that has a Zulu shield with two spears crossing, to symbolize power, loyalty, discipline and war. And that’s not all the sijils!

th: I remember our wonderful 2016 interview about your production design for the Academy Award-winning Moonlight, when we spent almost a half an hour just on the color palette! How did you wield the likes of black, purple, red and blue as a chromatic legend to understand Black Panther?

HB: Ryan printed out big blocks of colors on his walls. I walked into his office and went, “What is this?” He told me, “These are the colors that we are going to associate with the tribes and the people.” Black is our royal color. It’s also the color of Panther. Purple is a royal color as well. You’ll see Rwanda in those colors. The three colors you’ll always see together are black, green and red. Black is T’Challa’s color; green is the River Tribe color and Nakia, played by Lupita Nyong’o, is always in green. She’s a River Tribe war dog. And the female warriors of Dora Milaje are red, which is also the color of the Maasai tribe of Tanzania and Kenya. You’ll always see Okoye (Danai Gurira) in red. The Jabaris’ color was white. When you look at Panther, Nakia and Okoye walk into the casino and they’re all standing next to each other, they’re the colors of the pan-African flag. These Wakandas now in South Korea represent the African Diaspora -- how we all went around the world.

th: What about blue and Erik Killmonger?

HB: The first thing you’ll see in Oakland is blue, which is how you understand that we’re in Killmonger’s world. You will always see the blue before you see Killmonger. You know he’s coming. It’s a huge giveaway! I just said it! I don’t want to give too much away in the Easter eggy thing – I know people want to work for it -- but that became this really cool and interesting precursor.

th: “Cool and interesting” also goes for Ruth E. Carter’s costumes. Give a snapshot of how you two collaborated.

HB: Oh gosh, Ruth Carter, ya’ll!

th: To what extent did you guys talk about color?

HB: Oh, all the time. She’d come on the sets with her palette. And I’d be sending her artwork constantly. I’d go over to her warehouse and I’d be walking through this maze of racks and look up: There’d be African masks and beautiful artwork everywhere. Her mood board was this giant 12’ by 40’ wall. It’s Ruth Carter, so everything she’s showing me I’m melting over.

th: I read that she got permission to use the Basotho blankets from the tribespeople. Did you approach any sources to request their blessings?

HB: Wakanda is a pan-African place. Using a Timbuktu building as the inspiration for a sacred space where the elders go – that’s paying homage. So I never really felt like, “Who do I need to go and talk to about this Timbuktu building from 5,000 years ago?” On the other hand, the Basotho blankets are trademarked. Each has a meaning, and certain characters get certain blankets. Ryan fell in love with those wool blankets when he went to Lesotho. He was sending me pictures and saying, “This is what I want for the Border Patrol so they can hide their weapons underneath the blanket.” We certainly wanted to get permission from the Basotho people who use them for their livelihood, for shepherding and horseback riding.

th: How did cultural appropriation come into the conversation?

HB: We made sure that people were part of the process. We actually had some Lesotho shepherds riding the horses. They needed to be part of the process. It’s the artist’s responsibility to pay homage and give credit where it’s due and to have respect for other traditions and cultures.

th: What can you tell us about those intriguing white symbols on the pillars in the Throne Room?

HB: That’s writing from Nigeria from the 4th- 5th centuries. It’s called Nsibidi. It’s one of the first languages. The Leopard Society that kept some of the symbols secret. The symbols have meaning and you put them together in a pitctographic way that’s aesthetically pleasing. The meaning then becomes subjective and you can say the same thing in many different ways. One of the women in the film is from Nigeria, and she instantly read the columns. And I’ve been watching videos of people cracking the codes. Back to your question about evolution in the sets, T’Challa’s throne chair has a futuristic version of Nsibidi, as if the evolution of the language.

th: We also see an evolution of three kinds of aircraft. How did you blend technology and nature?

HB: We first started playing around with biomimetics with the aircraft. There’s the Royal Talon Fighter, which is like Air Force One. Then we’ve got the Town Fighters, which is like F-1 fighters. And then there are the Dragon Flyers, which are like helicopters. The Dragon Flyers were the first aircraft we started on. How does a Dragon Flyer defend themselves? When they land, what do their wings do? Even though we were in a fictional world, I still needed to understand how things would work if they did work. I talked to dozens of experts – and pilots -- about how to make the hologram that covers Golden City so other aircraft feel that that’s the altitude they’re flying over.

th: What went into creating the heart-shaped herb?

HB: There’s the heart-shaped herb that gives power, and then there’s the death herb that takes it away. We put the royal color purple in the life-giving side. Originally we wanted the death side to feel like the ghost of the flower. But we also had to be practical, since we put lights inside of them. So when Forest Whitaker’s Zuri is picking it, he’s actually picking it off the ground. It didn’t look so great when we did the wilted version. So we went with black. We’re still in the royal colors. The first time we see the death herb used is in the pool, so we wanted to relate it back to the Panther. The flowers were made after after my favorite flower: the black calla lily. That’s another Easter egg for you!

th: One of the biggest surprises is to discover how much of the set was actually constructed and not CGI.

HB: We constructed an actual set perhaps more than any other Marvel movie. The Flying Town Tiger had to be special effects. But we actually built the bus in Steptown and then CG’d it to float. Everything inside the aircraft is built.

th: What material was Warrior Falls built from?

HB: We brought in industrial-grade blocks of styrofoam, about 25,000 cubic feet in all. After several iterations of 3-D digital models, we had a clay model handmade of the cliffs. At that time I was traveling and came back wanting the look of Oribi Gorge in KwaZulu, Natal in South Africa as the main reference for the rock in Warrior Falls. So that horizontal slab and the shapes and the triangles and the long pieces that you see, that’s all from Oribi Falls.

th: How long did just Warrior Falls take to build?

HB: Months! We had 150,000 gallons of water running through that set for the waterfalls. It was about 125’ long by 40’ tall, and the pool was about 80’ by 60’ and about 20’ deep with two tunnels in it.

th: And what inspired the Hall of Kings?

HB: I looked at Angkor Wat, the way that the tree comes into the structure and the mosque.

I looked at things from all over the world, not just in Africa. For example, I used a specific texture, how the water line is black and then it goes into grey. That would be at a ruin in Vietnam, taking that gradation and seeing how powerful it made the structure.

th: What tradition were you drawing on for the Throne Room?

HB: In Mali buildings are made out of mud and clay to keep the buildings together, and they’re more of a square pyramid at the top. They use scaffolding, which is an ingenius way to be able to repair the buildings. They look like spikes, but they’re logs you can climb out on. In the Throne Room, the elders are sitting on red clay, which is the top of an ancient pyramid.

th: How did you figure out the scale of the constructions?

HB: In square miles and population, Wakanda is probably the same size as Britain. So I first modeled the palace after the size of the Buckingham Palace, which is 389’ x 469’ x 30’ tall. It ended up being quite a bit bigger because we had these two huge towers -- about 135,000 square feet.

th: How did working on a studio blockbuster differ from indie productions?

HB: On Moonlight I had a team of five. With Black Panther there were times when four or five sets were being worked on, so it could be anywhere from 150 – 500 people.

th: Was it scary?

HB: Ryan described taking on Black Panther like eating an elephant. If I ever stood back and looked at it, it was very overwhelming. But it really was one bite at a time.

th: Is that your advice for aspiring production designers?

HB: (Marvel Studios Executive VP of Physical Production) Victoria Alonso gave me some wonderful advice: “Every day you say to yourself, ‘I’ve done my best and my best is good enough.’ ” I had to say that to myself every single day!

th: What was was your emotional “in” to the production?

HB: I had to become a Wakandan. I knew Wakanda that well. I knew how to get to my aunt’s house in the River Tribe and I knew which train to get on. If I wanted to go visit a friend in Steptown, I knew which bus to take down the street. I knew how to get the hyperloop. In order for anyone else to look at what I’d done and believe it, I had to believe it first.

th: I recall how critical transportation was for you in creating the look for Moonlight. And for Black Panther?

HB: Getting around is who you are as a person and how brave you are in the world. Ryan grew up using the BART system in San Francisco. I did a lot of research of Elon Musk’s hyperloop. We decided it’s how Wakandans get around the entire country. So we made out a route of where it goes in each province. Each province is the size of a city, with Golden City being the capital, the largest city of Wakanda and approximately the size of Manhattan. Each province has its own BART system.

th: It must have felt like you lost your home when this production was over. Were you mourning the loss?

HB: I didn’t even realize I was grieving. I never knew that happened on a film, so I didn’t know what was happening to me for a very long time. My whole body went into this mode and I didn’t know what to do with myself. It was almost a depression. You spend a year with these people creating a world that you become a part of. You live here. And then you’re just ripped out suddenly when they say, “Picture wrap,” it’s done. I did go through a long mourning period of at least five months.

th: What have you done since Black Panther?

HB: I recently worked on two small projects with Dee Rees. You can see one of them on the night of the Oscar.

Photos

1) Erik Killmonger (Michael B Jordan) challenges T’Challa (Chadwick Boseman) at Warrior Falls. Photo courtesy of Walt Disney Studios/Marvel Studios.

2) Photo of Wakanda’s Golden City, courtesy of Walt Disney Studios/Marvel Studios.

3) Hannah Beachler at Blyde Canyon, South Africa. Photo by Ilt Jones, courtesy of Walt Disney Studios/Marvel Studios.

4) Throne Room in “Black Panther.” Photo courtesy of Walt Disney Studios/Marvel Studios.

5) Lupita Nyong’o as Nakia, Chadwick Boseman as Black Panther and Danai Gurira as Okoye in “Black Panther.” Photo courtesy of Walt Disney Studios/Marvel Studios.

6) Set Decorator Jay Hart and Production Designer Hannah Beachler on South Korean casino set. Photo by Alex McCarroll, courtesy of Walt Disney Studios/Marvel Studios.

7) Production designer Hannah Beachler. Photo by Brian Douglas courtesy of courtesy of Walt Disney Studios/Marvel Studios.