Woody Allen Escapes into "Magic in the Moonlight"

"Magic in the Moonlight" could be the name of a celebrity perfume or a Walt Disney animation. But Woody Allen's new film bearing this moniker is a romantic comedy about illusion and delusion -- and the enchantments of the French Riviera.

It opens in 1920s Berlin with an elephants-and-all performance by the great illusionist Wei Ling Soo, who cocks a Colin Firth sneer underneath his faux Fu Manchu. Offstage, shorn of his Oriental guise, he reverts to being the hardened British curmudgeon Stanley Crawford, who holds charlatan psychics in special contempt. “From the séance table to the Vatican, they're all fake,” he sniffs, ascribing to one particular offender “all the charm of a typhoid epidemic.” When Stanley catches word of the sensational medium Sophie Baker (Emma Stone), the gauntlet is thrown down: posing as a businessman, he will attend her performance in the Côte d'Azur and out her as the phony she surely must be (as seen in photo 1 & 2). For this crusading vigilante, all spiritualism is bunk and there's a rational explanation for everything. Yet even he becomes ensorcelled by the cute clairvoyant, and cedes the possibility of mystic powers. How exhilarating to imagine that there's more to the universe than what cold logic dictates -- and that life isn't meaningless after all!

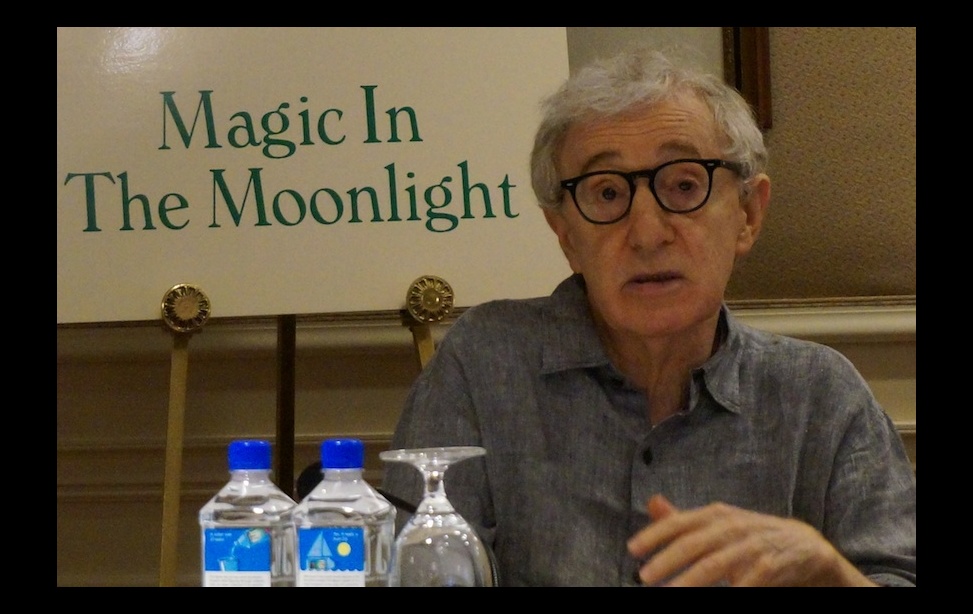

Listening to Allen wax philosophical during a recent press conference in Manhattan (as seen in photo 3), you get why so many of his characters have grappled with this knotty issue throughout his prolific career:

“I firmly believe, and I don’t say this as a criticism, that life is meaningless,” he lamented. “I’m not alone in thinking this. There have been many great minds far, far superior to mine, that have come to that conclusion. And unless somebody can come up with some proof or some example where it’s not, I think it is. I think it’s a lot of sound and fury signifying nothing, and that’s just the way I feel about it.

“I’m not saying that one should opt to kill oneself,” Allen continued with his nasal Brooklyn lilt. "But the truth of the matter is, when you think of it, every let's say 100 years, there’s a big flush, and everybody in the world is gone. And there’s a new group of people. And then that gets flushed, and there’s a new group of people. And this goes on and on interminably — and I don’t want to upset you — toward no particular end, no rhyme or reason.

Working himself in to an existential lather, he elaborated, “And the universe, as you know from the best of physicists, is coming apart, and eventually there will be nothing, absolutely nothing. All the great works of Shakespeare and Beethoven and da Vinci -- all that will be gone. Now, not for a long time, but gone. Much shorter than you think, really, because the sun is going to burn out much earlier than the universe vanishes, so you don’t have to wait for the universe to vanish. It’ll happen earlier than that. So all this achievement, all these Shakespearean plays and the symphonies, the height of human achievement, will be gone completely. There will be nothing, absolutely nothing: no time, no space, nothing at all. Just zero.

"So what does it really mean to get exercised over trivial problems?" Allen shrugged. "That's why over the years I've never written or made movies about political things; because while they do have current critical imporance, in the large, large scheme of things, you know, only big questions matter. And the answers to those big questions are very, very depressing. What I would recommend -- this is the solution that I've come up with -- is distraction.

"That's all you can do. You can get up. You can be distracted by your love life, by the baseball game, by the movies, by the nonsense: Can I get my kid into this private school? Will this girl go out with me Saturday night? Can I think of an ending for the third act of my play? Am I going to get the promotion in my office? All this stuff, but in the end the universe burns out. So I think it's meaningless. And to be honest, my characters portray this feeling. Have a good weekend."

The horn-rimmed prophet of doom went on to advocate pure entertainment. “I’ve thought to myself at times that there’s a story in two filmmakers. One filmmaker makes films that are deep, intellectual, profound and confrontational, and the other one makes purely vacuous, escapist films. And I’m not sure if the one who makes the escapist films is not making a bigger contribution than the one who makes the deeper films.

“You’re in the world and it’s so terrible and all these things are going on, and you go into a dark room, the movie theater, and you’re there for an hour and a half, and Fred Astaire is dancing. It’s like drinking a cold...lemonade on a hot day, and you’re refreshed, and you walk back out into the terrible heat, and you can take it for another few hours, maybe more. The artist can’t give you an answer that’s satisfying to the dreadful reality that’s your own existence, so the best you can do is maybe entertain people and refresh them, and then they can go on and meet the onslaught until they’re sunken and crushed and then somebody else comes along and picks them up a little bit.”

For Allen's part, he's been "escaping (his) whole life," on either side of the camera. "...I've been living in a bubble and I like it," he offered. "I'm like Blanche DuBois that way. I prefer the magic to reality, and have since I was five years old..."

Magic in the Moonlight is the indie conjurer's latest attempt "to try and find some solution or some reason to accept things." Darius Khondji's French Riviera cinematography, Sonia Grande's flapper costumes and Colin Firth's gait alone recommend it as a visual stop-gap. For all the film's sensuous charms, though, it manages to compel meditation on the many dyspeptic questions it lobs. It might even make you believe in mediums: in his characters' deftest verbal jousts, Allen may well be channeling the spirits of Jane Austen and George Bernard Shaw.

From Stanley's mulish denial of his growing affections alone, you could swear Allen was saluting "Pygmalion." So it came as a bit of a surprise when the writer/director acknowledged that Shaw's play "is the best comedy ever written," but that it was nowhere on his radar. Firth, who also attended the press conference (along with Jacki Weaver, whose character hires Sophie to conduct a seance with her dead husband) echoed this stance (as seen in photo 4). On his way out, the lanky British star told thalo.com that Allen "never mentioned Henry Higgins." How to explain the astonishing feat that his Stanley Crawford slipped the Woody Allen crucible and more closely resembled My Fair Lady's Rex Harrison than the ever-reincarnating avatar of the neurotic, gesticulating intellectual? Chalk it up to magic in the moonlight.

Photos Credits:

Photo 1: Emma Stone and Colin Firth (L - R) in Woody Allen's "Magic in the Moonlight." Photo courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics.

Photo 2: Colin Firth and Emma Stone (L - R) in Woody Allen's "Magic in the Moonlight." Photo courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics.

Photo 3: Photo of Woody Allen by Brad Balfour.

Photo 4: Photo of Jacki Weaver and Colin Firth (L - R) by Brad Balfour.