Alfonso Cuaron Lifts Off with "Gravity"

Alfonso Cuaròn soared at the 86th Academy Awards, where he was named Best Director for Gravity. The 3-D space odyssey drew another six awards — Best Visual Effects, Cinematography, Editing, Sound Mixing, Sound Editing and Musical Score (as seen in photo 1). On a wintry night several weeks prior, the 13th snow storm of the season had frozen the Film Society of Lincoln Center's plans to host Cuarón in a conversation. The acclaimed Mexican director, whose lift-off to New York was aborted, was instead astral-projected by video Skype.

Cuarón is perhaps best known to American audiences for his screen adaptation of the children's book A Little Princess; his Mexican road comedy Y Tu Mamá También; and his sleight of hand on a studio franchise, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. Children of Men added to his roster of Oscar nominations and won critical esteem as well as a science fiction fan base.

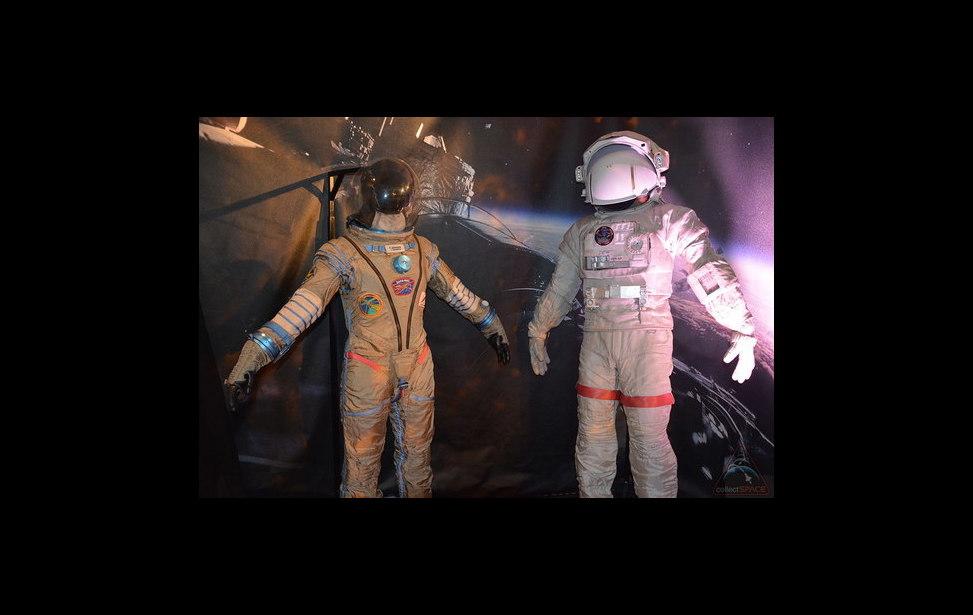

Science and invention surface anew in Cuarón's galactic thriller co-scripted with his son, Jonás Cuaròn. It stars Sandra Bullock as Dr. Ryan Stone, a medical engineer on her maiden voyage aboard the Space Shuttle Explorer. George Clooney's veteran astronaut, Matt Kowalski, spacewalks around her with his usual flirty banter until things go horribly awry: Houston warns that a Russian missile has knocked out a satellite, and its detritus is barreling in their direction. The rubble quickly devastates both the Hubble Space Telescope they had come to service as well as the Explorer, whose crew is now dead.

With 90 minutes to go until the space cloud reorbits their field -- and with dwindling fuel reserves -- the duo find their way to the blighted International Space Station. En route, Stone opens up about the traumatic death of her young daughter. Stone manages to latch onto the damaged ISS and to tether Kowalski's suit, but over her protests he detatches in order to save her from drifting away with him. Kowalski comes back to advise Stone just as she's giving up hope aboard a Soyuz capsule, though she soon realizes that his reappearance was just a hallucination. Armed with a new resolve, she connects with the Chinese space station Tiangong and commandeers its Shenzhou rocket designed to re-enter Earth. The bulk of this taut survival tale orbits Ryan's isolation in the cosmos (as seen in photo 2). Yet, the film itself is heaped with love. In addition to its Oscars sweep, it attracted three nominations from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Best Picture, Actress and Production Design.

The Q&A between Cuarón and Film Comment editor-in-chief, Gavin Smith, that followed the Lincoln Center screening gave the director a chance to delve into the bionic wizardry of the shoot and the all-too-human themes of the narrative. Cuarón talked about inventing a "completely new way of making a movie" in the tradition of Stanley Kubrick, Steven Spielberg and James Cameron. He explained that"a traditional CGI approach was not possible because of the physics of being in zero gravity." After much trial and error, he and his team -- including Academy Award-winning cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki and visual effects supervisor Tim Webber -- famously improvised a solution from scratch.

Cuarón recalled sending the script to "Chivo" (that's Lubezki's nickname), with the description that "it was just an intimate story of a woman dealing with her grief," requiring roughly a year to make "with some visual effects." As it happened, preproduction lasted two-and-a-half years, mostly to develop the technology. The shoot then straddled two summers: 11 weeks on the first go-round and back the following summer for another two weeks. The rig was just that complex. Cuarón joked about his own tech savvy, cracking that he "can google to look for a movie theater, but that's about it."

As for the actors' prep, Sandra Bullock put in five strenuous months. There were moves to work out with the stunt people and scenes to block with the animators, to say nothing of her efforts with the special effects department. Of the precise cues, positions and timings that Bullock had to reach amid virtual sets, Cuarón said she was like a dancer learning choreography, and the shoot, her performance. Not only did the regimen boost Bullock's strength, but it also chiseled her character's persona. Bullock "wanted to really be trim and give this androgenous feel throughout the first part of the film."

"The process allowed us to dig deeper and deeper into the emotional core of the scene," stressed the director. Explaining that Bullock was locked inside a 10' x 10' lightbox for her insular scenes, he noted that she opted to stay inside between takes. "She started using it as her own process," he marveled.

The Soyuz capsule was one of the production's only real sets. Yet far from delivering a respite from the demands of the virtual environment, it was the site of that particularly tough scene whereby Stone hallucinates Kowalski's return. And it's captured all in one take. "It's a big arc: it goes from the spirit of resignation to trying to kill herself to the moment of the epiphany of a new resolve," said Cuarón. "Because of the nature of shooting in a small space and the camera moving around, pieces of the set were floating in and out all the time," he added. "There were moments in which Sandra suddenly had to talk because the camera was passing; or the whole ship would have to rotate to allow Clooney to come in and rotate back for him to sit back down (as seen in photos 3 - 4). In all those cues she would never miss one single emotional beat."

The audience hung on Cuarón's every word. Those who came for the shoptalk were ecstatic, and the questers of deeper meaning more than met their match in Cuarón.

"It's about this astronaut who's drifting between the void and the possibility of life on the other side: the Earth," he mused. To finetune the observation, Cuarón qualified his heroine as the "victim of her inertia" who is "getting far away from human communication." He tagged the film as a "story about rebirth...of gaining a new knowledge of herself."

Whatever the struggles of the protagonist, an ongoing drama for the filmmakers was the battle between good science and good storytelling. On this heady behind-the-scenes adventure, Cuarón reminisced: "We had done a lot of research, so we finished the first draft feeling we were space experts. Then we engaged the advice of a scientist who works close to NASA. He just proved that we were morons. The script was so inaccurate in every way. So we started working very closely with several scientists and having conversations with astronauts to try to make everything as plausible and realistic as we could. We did a draft in which every single scientific fact was addressed, but it was a 300-page script filled with technicalities. And it was really boring. So we decided to just be as plausible as we can in the frame of our picture. What we were really concerned about is the behavior of objects in micro-gravity and no-resistance. For that there were a lot of computer simulations because it's very counterintuitive. (The final result) is full of holes. Look, it's a movie! I don't think that when Sandra (as seen in photo 5) goes into this fetal position...(and) rips off her clothes that she will have an adult diaper. So you have to make your choices."

Photo credits:

Photo 1: Sandra Bullock as Dr. Ryan Stone in "Gravity." Photo courtesy of Warner Bros.

Photo 2: Adrift the "Gravity" cosmos. Photo courtesy of Warner Bros.

Photo 3: (l to r) Sandra Bullock, George Clooney and Alfonso Cuaròn on the set of "Gravity." Photo courtesy of Warner Bros.

Photo 4: Prepping visual effects for the production of "Gravity." Photo courtesy of Warner Bros.

Photo 5: Sandra Bullock as Dr. Ryan Stone in "Gravity" Photo courtesy of Warner Bros.

A version of this article was previously published at www.jccgreenwich.org and filmfestivaltraveler.com