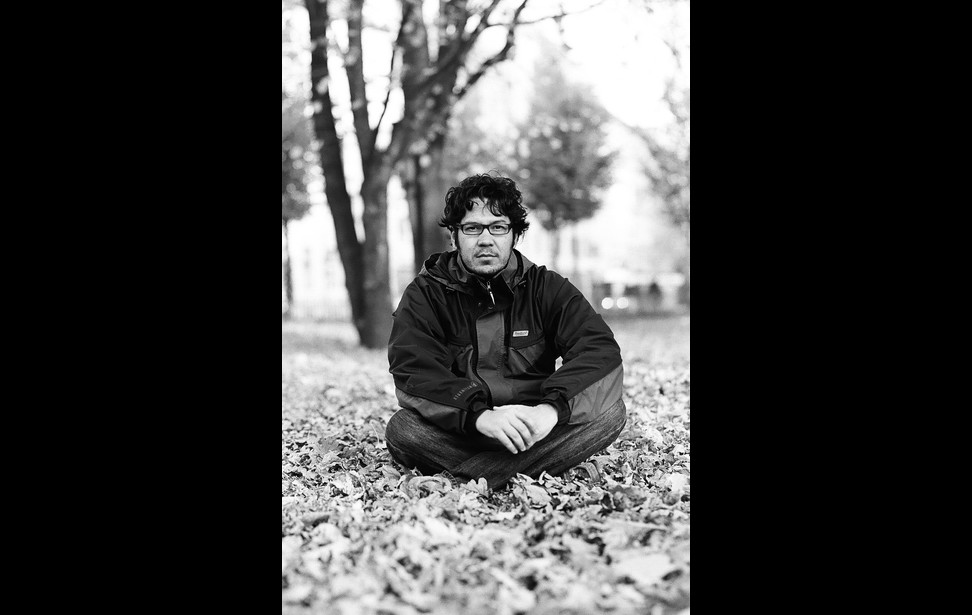

Luis Chaves - Acclaimed Costa Rican Poet

SAN JOSE, COSTA RICA -- “Poetry is not useful for anything. And therein lies its value,” Luis Chaves replied when asked to define poetry. Chaves (seen in Photos 1 - 3) is considered a leading figure in Costa Rican poetry. He has eight books under his belt with no shortage of awards and praise. The recipient of the Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Poetry Award and the III Fray Luis de León Poetry Prize, his success far supersedes his 42 years. He was gracious enough to agree to his inaugural English interview in his home in San José, Costa Rica that he shares with his wife and two daughters. It is the house he grew up in that belonged to his grandmother. It’s a typical Central American red abode spilling over with books, framed photographs of the children, with a small dog and black cat roaming about.

thalo: You studied agronomy at university. What drew you to that field, and do you see any correlation between it and your writing?

Luis Chaves: I was too young – like everybody else – and I wasn’t sure what to do. I was an average student. I had an uncle who was an agronomist, and I liked him very much. He told me about his work, and I liked what he said. Five years later, I graduated and only worked for two years. I was in love with literature since I was a kid. It’s strange because there were no books in my house growing up, no appreciation for art. My parents didn’t even go to the movies. I knew I loved reading. But I wasn’t interested in studying filologia, which is the closest thing to a creative writing degree in Costa Rica. I just decided it was time to accept my destiny.

th: Publishing in Costa Rica is very different from the U.S. How did you get started?

LC: My first book was self-published and I paid for 200 copies to be printed. That was the only time I paid. It’s a terrible, terrible book. But it’s important to me because it was a physical representation of my decision and I knew I would never go back to agronomy. From now on, I had to make a living close to literature. No one lives by it alone, but it was my new world. The next book, I won a competition and it included a cash prize and book deal. I won another prize in 2004 and it was nearly $25,000 which for me, it was just, “wow.”

th: Tell me about your involvement with Los Amigos de lo Ajeno.

LC: From 1998 – 2004, I had this small magazine. We produced 11 issues. I did this with an Argentinian writer, Ana Wajszczuk, who I met here. It was free and we published a lot of young poets that didn’t have many outlets in Costa Rica. In 2003 she went back to Argentina to get married. She invited me to her wedding. I went and was going to stay for three months and I stayed for three years. One issue we featured a professional wrestling match, another we featured a gay club in San José with transvestites reading poetry. We had a lot of fun, we were young. We had the energy, no kids, no family, no responsibilities.

th: In an interview with La Nacion in 2009, you said everything you read leaves sediment. What are some books that you return to over and over?

LC: I learned a lot more from Anglo-American poetry more than Latin American poetry. I love a lot of Latin American poets but there was a time in my life where I tried to mix what I liked about some Latin American poets and the kind of poetry that William Carlos William and Kenneth Rexroth wrote. I like simplicity, which is not that simple. They didn’t use difficult words. They were very austere. Very unaffected writing. One of my favorite writers of all is Celine. When I was a kid, I loved songs that told stories and it was a way for me to practice my English. Bob Dylan, Pink Floyd and Dire Straits.

th: San José seems to be an integral part of your writing. How does your environment, and your identify as a “Tico,” influence your writing?

LC: There are a lot of physical and psychological landmarks that have to do with where I grew up. There are a lot of words I use that come from my places. It’s not only the places, but the people that surrounded me, involved in my writing.

th: You write about your parents quite a bit. Do you consider elements of your work “confessional?”

LC: Sometimes. Yes, it’s confessional. There’s a lot of autobiography in what I write mixed with fantasies. I have little imagination in some ways. I cannot see myself creating a psychological profile of 30 characters. That’s not me. I cannot do that. So most of what I write is…true. It happened or it happened very closely to the way I write it. I just do it because I cannot stop. The periods of time when I’m not writing, I feel bad. I feel upset.

th: What’s your reaction to being named as a top writer in Costa Rica?

LC: Nah, no. That’s not for me to say. I think we’re all part of a long chain of people. That’s where the sediment also comes. We write from what we have read. From all the things we’ve read – the things we like and the things we don’t like. What does that mean, anyway? You hear that about a lot of people and sometimes you say, “What?” And it’s not false modesty. I just really don’t take time to think about that.

th: What route do you see the future of poetry taking here?

LC: There are three or four new, independent publishing houses. I think it’s healthy. The internet has also opened a lot of space for a lot of writers. There are a lot of young writers publishing poetry. I like Esteban Chinchilla, he’s also a photographer. Silvia Piranesi I like. They are the ones I am most interested in.

Photographs courtesy of Esteban Chinchilla