“Loving Vincent”: Interview with Directors Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman

By Laura Blum

Who hasn’t looked at Vincent van Gogh’s masterpiece Starry Night and felt the brushstrokes swirl? Like many of the Dutch artist’s oils, the dabs of color rolling around the stars and moon give an illusion of movement. Now along comes Loving Vincent to wrestle that cinematic quality into a feature film.

Despite the vibrant palette, the story shades noir. Using van Gogh’s paintings to sleuth out the murky circumstances surrounding his alleged suicide, it unfolds through interviews with the subjects he so viscerally portrayed.

The story of how Loving Vincent was made is as dramatic as the work itself. Directed by Polish painter/filmmaker Dorota Kobiela (Little Postman, The Flying Machine) and her husband, producer Hugh Welchman (Peter and the Wolf), the production brought together 125 painters to make what is being touted as “the world’s first fully painted feature animation.”

All told, they remade more than 120 of van Gogh’s most celebrated paintings. Similarly, the narrative draws on the Post-Impressionist icon’s writings, a trove of some 800 hand-scrawled letters. “We cannot speak other than by our paintings,” he noted in his last letter before his death. “Those were the words that literally inspired the whole idea,” Kobiela tells thalo.com in a three-way sit-down during her and Welchman’s recent trip to New York.

What was it about van Gogh and his turbulent story that initially compelled Kobiela? She recalls her own encounter with depression while a student at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. “I was working very intensely and I wanted to prove that I can do everything, but at some point, you realize you’ve sort of failed in your plans.” The Polish lilt in her voice adds to a sense of lingering introspection.

“As I was struggling with my own situation, I started reading van Gogh’s letters,” Kobiela muses. Those letters, along with the writings of Danish thinker Søren Kierkegaard, informed her master’s thesis about the relationship between art and mental health.” In particular, she wanted to crack, “What influences what?”

That line of questioning still intrigued Kobiela when she later set out to make an animated short about van Gogh’s life. The overlaps with her own story, I suggest, must have lent added resonance to the feature-length project it ultimately became. They have.

Since both filmmakers seem game for entertaining purported links between van Gogh’s aesthetic and his medical condition, I trot out a few favorites for them. For example, what did they make of the argument that van Gogh’s penchant for the color yellow and for corona-like effects is associated with digitalis toxicity, or that one of van Gogh’s portraits of his physician, Dr. Paul-Ferdinand Gachet, features foxtrot, the herb from which digitalis is derived? Or how about his beloved absinthe’s side effect of “yellow vision”?

“I love all those different theories about what his condition was,” Welchman grins. “There was a big exhibition at the Van Gogh Museum last year, and they concluded after 100 years of scholarship that they didn’t know what he had.” Possibilities include bipolar disorder, neurosyphilis, sunstroke, acute intermittent porphyria, temporal lobe epilepsy and Ménière’s disease, for starters.

“Vincent did suffer from mental illness and he did have hallucinations, but he was also a very considered artist, even if his execution was very obsessive and very fast,” says Welchman. “In his letters he was writing about his new approach to color for two years before it all came together. He went down to the South of France looking for the sun-scorched colors. There’s very much a thought-through process that went into getting those yellows.”

“Certainly his color combinations and his complementary colors more stem from painters like (Eugène) Delacroix and (Adolphe) Monticelli and from various artists with whom he was experimenting with Pointilism and Post-Impressionism than from they do from his mental illness,” adds the British filmmaker. And about that supposedly mind-tricking spirit, he clarifies, “Vincent was drinking cheap brandy and wine in the South of France, but not absinthe.”

“His yellow period was influenced much more by Japanese art,” Welchman argues, noting that Japonism was “a big thing” in the 1880s in Paris. “One day (his brother) Théo, who paid for everything, came home from work and found that Vincent had bought over a thousand Japanese prints.” Having taken up with van Gogh for as long as they have, the filmmakers show a granular command of his biography and work.

It served them well during the seven-year production including two years of generating 65,000 animated frames. First came creating the reference materials for the painters, a phase that involved live action.

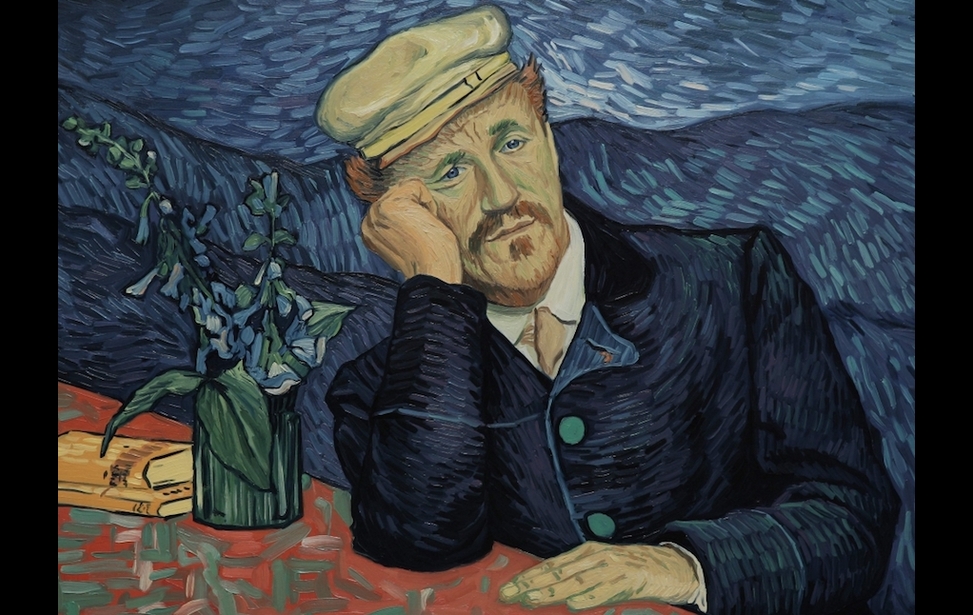

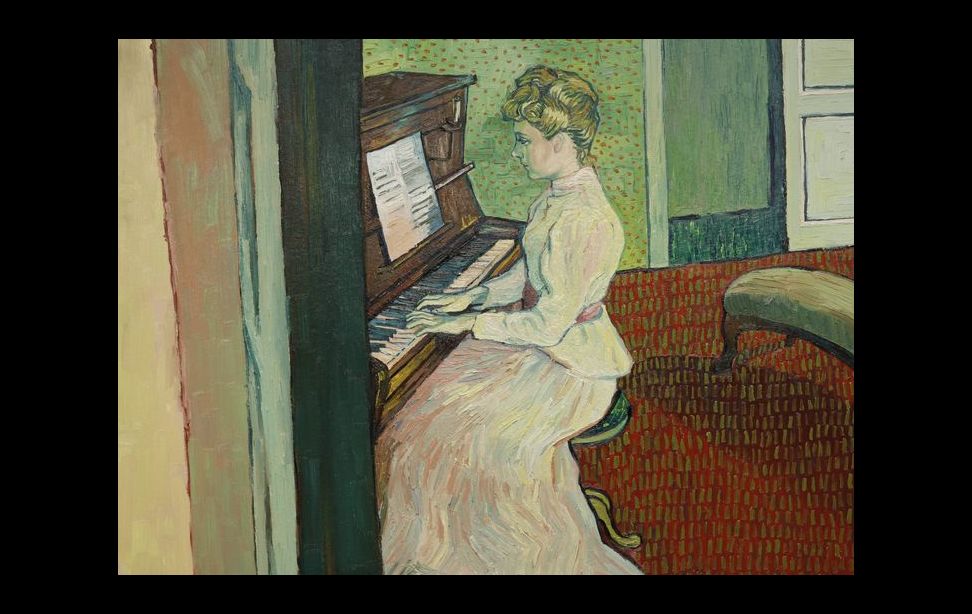

Limited funds and a London-based shoot meant casting British and Irish actors, yet with the added wrinkle of having to match them with van Gogh’s subjects. “We were looking for the actors who were well known but also looked like the paintings,” Welchman explains. Douglas Booth’s good looks and stature resembled his character’s, Armand Roulin, on canvas. And at 6’4”, the imposing, broad-faced Chris O’Dowd fit the bill for his father, Postman Josef Roulin, who was the 1880s equivalent of 7’ today. Reportedly the hardest role to fill was Dr. Gachet. “Vincent wrote that he wanted that painting to have the heart-broken expression of our age,” Welchman relays. “Jerome Flynn breaks my heart every time I watch the film.” Dr. Gachet’s daughter Marguerite was considerably easier to target, given that Saoirse Ronan had been on Kobiela’s wishlist from the get go.

If selecting the actors brought challenges, these had nothing on what it took to cast the artists. Asked about the process of “auditioning” the painters, Kobiela says it began with a pool of 2,000 portfolios, from which the filmmakers selected 300 to take a three-day test. The 60 who made the grade then had to successfully complete an immersive six-week training.

For Kobiela, the brief was to pair the artists’ fortes with the work they’d be doing. One example she gives is Christos Marmeris, a Greek artist who specialized in female characters such as Adeline Ravoux (Eleanor Tomlinson), “because he didn’t really like the thick impasto.”

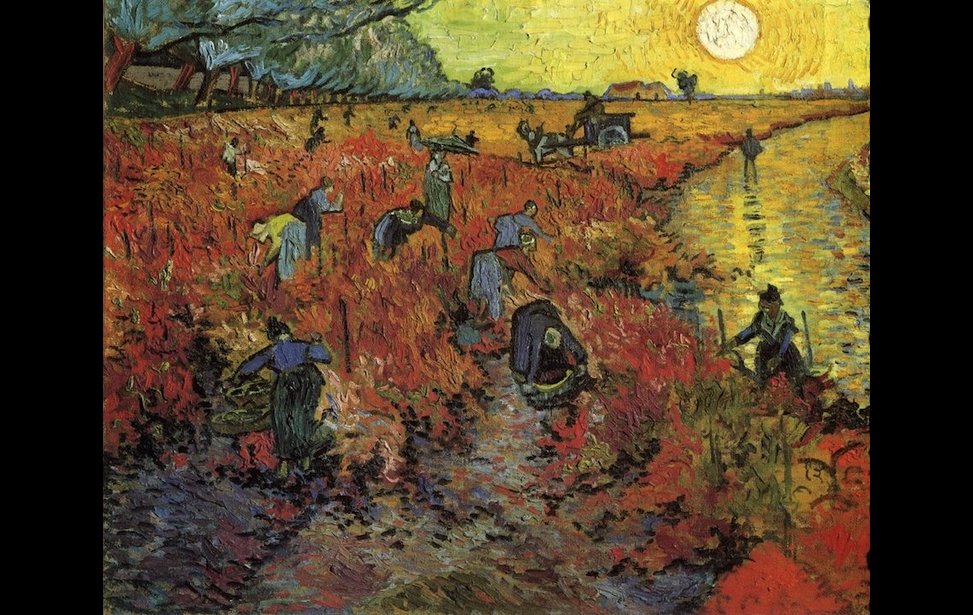

The core team numbered 55 painters. Kobiela recalls the stumping that went on for choice tableaux. “The Red Vineyards got lobbied for a year,” she reports.

The artists worked in oil on canvas boards mostly with the help of projected outlines indicating intended movement. “Once the painting started, it was like the puppet animations–stop motion--we’d done previously,” says Welchman, whose similarly-wrought short film Peter and the Wolf had nabbed an Oscar a decade earlier.

But before the material reached the artists, it had undergone a improvised process that encompassed storyboarding, computer previsualization, edits and rough compositing. Also in the mix was a battery of 2-D, 3-D and visual effects software programs, yielding a workable mesh of the actors’ live-action green-screen shoots and either recreations of the Dutchman’s paintings or fresh imaginings based on his rhythmic, pulsating style.

Whether black-and-white or multi-hued, the painted tableaux pack a varied palette of emotions. The Sower is a case in point. “What Vincent said about the sower in the wheatfield was that for him it was the picture of death, but not a sad death,” says Welchman. “He was conveying his sense of the cycle of life under this beautiful sun. The sower image was something that he very much related to religion at some point. He also related it to himself, the painter, in that he was sowing for the next generations.”

Creating heightened dramatic tension also meant reenvisioning the original work. Take Bedroom in Arles, for example. “The original is very hopeful, idyllic and ordered,” says Welchman. “Vincent wanted to convey that sense of a home there. We invert this in the film by turning it into a nightmare, because that bedroom was also where the police found him covered in blood, with his ear cut off.”

We’re off on a fresh tangent now, starting with what the filmmakers watched for inspiration, and inexorably veering into the big mystery at the heart of Loving Vincent: Did van Gogh do himself in or was he offed by young ruffian René Secrétan? The answer to the former ranges from noir classics such as The Big Sleep, Double Indemnity and Citizen Kane, to investigative documentaries including Errol Morris’s Thin Blue Line and Carol Morley’s Dreams of a Life, to the POV masterworks Carl Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc and Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon.

Which brings us to the latter query, and to Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith’s Van Gogh: The Life. “Before their book reinvigorated the rumor that he was shot by the boys, we already had a list of reasons why we doubted that he committed suicide,” says Welchman. “Certainly we wondered why he would commit suicide then, when things were going well for him.” Yet, as Welchman notes, “The only eye-witness that gave evidence was Vincent, and he said he shot himself.”

Was van Gogh covering for the boys, as the authors claimed, and was it an accident? Welchman concedes it’s a possibility, but then why would van Gogh have told Théo, the police and Dr. Gachet that he was the one who’d pulled the trigger? What’s more, Welchman stresses, of the people who knew van Gogh best, none was surprised that he would take his life.

“Do you both see eye to eye about van Gogh’s ending? I venture. Kobiela responds that she doesn’t “have very strong arguments that something happened or not.” Welchman chimes in, “There is no proof either way.”

I weigh in that van Gogh made allusions to suicide in his writings, and that he felt he was a crushing burden on Théo. “He wrote that maybe the world would be better without him,” allows Welchman, adding, “He also made very strong categorical statements against suicide. He said in a letter, ‘To commit suicide is to make murderers of your family and friends.’ He felt it was irresponsible toward your family and friends to commit suicide because you’re saying they let you down.”

“Even if it wasn’t the worst phase of depression that he seemed to go through in his adult life--there seemed to be periods when he was much more alone, much less successful and a lot less healthy--it also could have been a cumulative thing,” Welchman offers. “It’s one thing to be broken-hearted in your 20s. It’s another thing in your late 30s, when you’ve tried so hard at so many things and you’re still struggling with basic relationships.”

For all the mystery surrounding van Gogh, one thing is plain: his life and death are a storytelling goldmine that the talented duo wish to keep tapping. There’s no plan for a feature sequel, though don’t be surprised if the scrapped Paris, St. Rémy and Dutch chapters of the original 300-page script find their way into short films. Meanwhile, fans of their exquisite animation will be thrilled to know that another painted feature is in the works, this time a horror film inspired by Francisco Goya’s etchings The Disasters of War.

Variety ranked Kobiela among its 2017 “10 Animators to Watch.” Taken together with Welchman’s trophy shelf, that sounds like solid advice.

Photos:

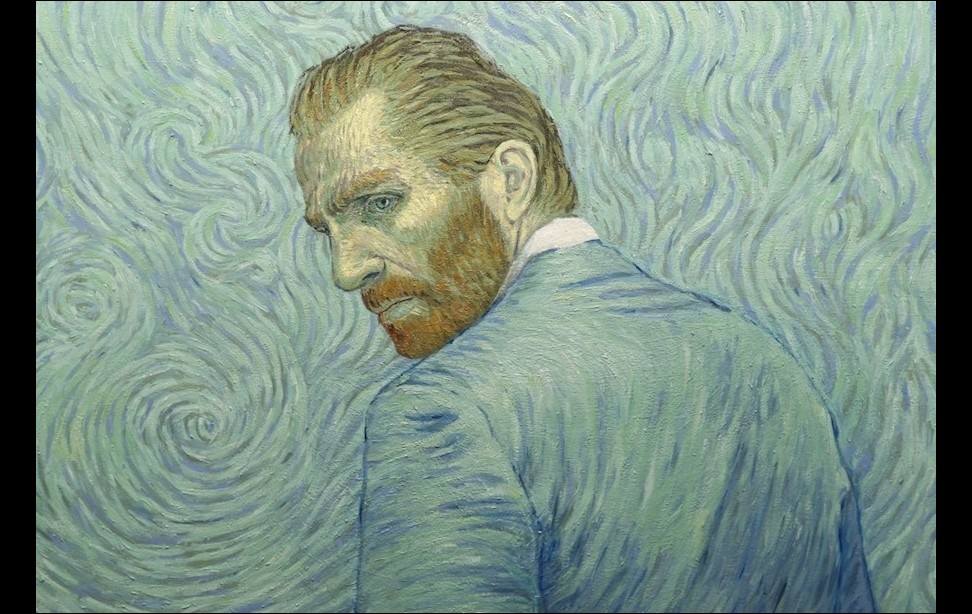

1. “Vincent,” painted by Anna Kluza. Robert Gulaczyk as Vincent van Gogh, inspired by van Gogh's self portrait. Photo courtesy of Good Deed Entertainment and BreakThru Films.

2. “Dr. Gachet,” painted by Piotr Dominiak.

Jerome Flynn as van Gogh’s controversial physician, Paul-Ferdinand Gachet. Inspired by van Gogh's “Portrait of Dr Gachet.” Photo courtesy of Good Deed Entertainment and BreakThru Films.

3. “How I Remember Him,” painted by Marlena Jopyk-Misiak

In this “Noir Vincent” shot, Armand Roulin (Douglas Booth) enters “Bedroom in Arles” and is confronted by the spectacle of Vincent covered in blood on the "night of the ear."

Photo courtesy of Good Deed Entertainment and BreakThru Films.

4. “He Had a Breakdown, It Happens to People,” painted by Joanna Maleszyk.

Postman Roulin (Chris O’Dowd) is sitting with his son Armand at van Gogh’s “Café Terrace at Night,” reminiscing about the artist. Photo courtesy of Good Deed Entertainment and BreakThru Films.

5. “Marguerite Gachet,” painted by Bartosz Armusiewicz

Saoirse Ronan as Marguerite Gachet, the mecurial doctor's daughter. Inspired by van Gogh's “Marguerite Gachet at the Piano.” Photo courtesy of Good Deed Entertainment and BreakThru Films.

6. “What Dr. Gachet? No, I Wouldn’t Have Said That,” painted by Christos Marmeris.The second of five Adeline Ravoux (Eleanor Tomlinson) close-ups at the window. Here she is commenting on the supposed friendship between Dr. Gachet and van Gogh. Photo courtesy of Good Deed Entertainment and BreakThru Films.

7. “The Red Vineyard,” painted by Jerzy Lisak Armand Roulin travels through “The Red Vineyard” landscape on his journey home. Photo courtesy of Good Deed Entertainment and BreakThru Films.

8. “I Need a Drink,” painted by Karol Nienartowicz. This black-and-white scene from Café du Tambourin in Paris features Vincent’s friends Père Tanguy and Emile Bernard. Photo courtesy of Good Deed Entertainment and BreakThru Films.

9. “Get Outta Here,” painted by Ewa Golda.This flashback takes place following Vincent's departure from Arles hospital, after cutting off his left ear, seemingly fully recovered from his mental illness. He was harassed by kids as young as 10 years old. The featured location was inspired by van Gogh’s “Field with Poppies” (1889, St. Rémy), painted 13 months after he left Arles. Photo courtesy of Good Deed Entertainment and BreakThru Films.

10. “Chaponval,” painted by Anna Wydrych Design painting combining van Gogh’s paintings “Houses at Auvers” and “Thatched Cottages at Cordeville.” Photo courtesy of Good Deed Entertainment and BreakThru Films.

11. “Loving Vincent” directors Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman. Photo by Laura Blum.