“The First Monday in May”: The First Night at the Tribeca Film Festival

Finally you can finally stop kicking yourself for missing The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s blockbuster show China: Through the Looking Glass. In making it the focus of The First Monday in May, filmmaker Andrew Rossi has you covered.

Rossi grants a privileged look behind the scenes at the process of conceiving and mounting what went down in Met history as its best-attended exhibition. There’s more texture and fiber onscreen than what you could reasonably expect from the original spectacle.

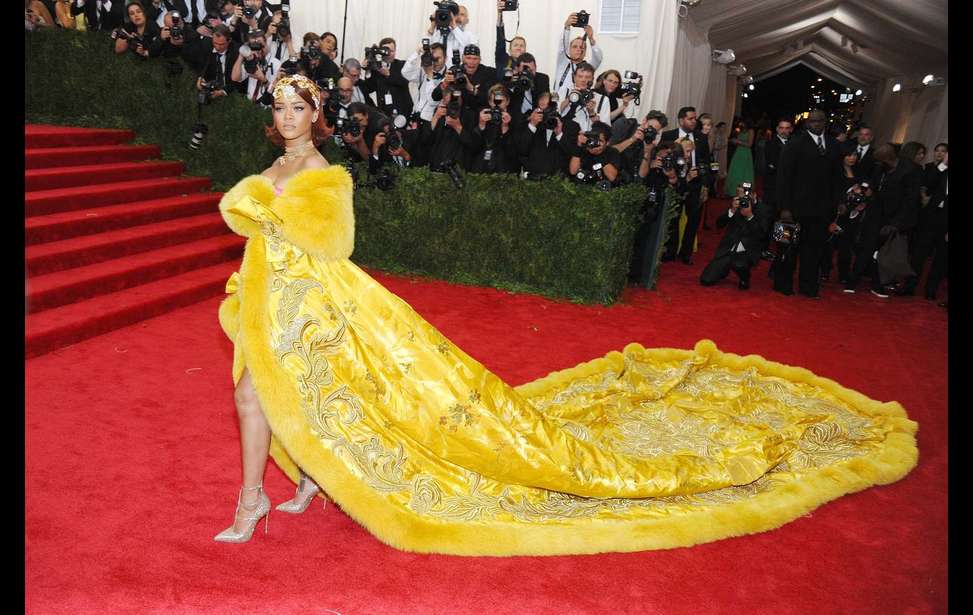

The referenced May Monday is the 2015 Met Gala. As the fateful date nears, Bolton and his team race against the calendar to pull off the exhibition for the guests to see. And what guests they are. George and Amal Clooney! Jean-Paul Gaultier! The queen of the night, Rihanna! Leave it to Gala co-chair and Vogue editrix Anna Wintour to rope in a Who’s Who of celebrities and fashion potentates — and a tidy sum of $120 million.

"You need the mixture of art and commerce," Wintour observes. Her comment is as apt for couture in general as for the Met exhibition — and clearly too for the Gala. Engineering the seating arrangements seems as intricate as a NASA mission and arguably as high-risk.

The dewier protagonist of this vérité buddy film is Met curator Andrew Bolton, mastermind of the featured extravaganza about Chinese-inspired Western fashion. Graced with the reticent charm of a British school boy, Bolton is at once hailed as a creative and conceptual genius, yet he’s blushingly insecure in his ability to make timely strategic decisions. It’s sweet if surprising to see the reedy 48 year old express doubts about being up to Museum snuff. He even frets about keeping up with his own par; the 2011 sensation Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty drew a whopping 661,509 visitors. Mirroring Bolton’s struggle to transcend that “albatross,” Rossi lingers perhaps more than China merits on the marvels of McQueen.

But he gets the portraiture of his leading man just right. A brief lookback on Bolton’s boyhood is especially stirring. Everything has changed since his humble beginnings in Lancaster — where he first savored fashion through magazines — though perhaps little has changed of the dreamer behind his oversized glasses.

Not that Bolton is lost in a reverie. Intensely focused on the task before him — as the camera rolls he has eight short months to mount the show — the visionary curator shifts into high gear to make his globe-spanning ideas materialize.

Forget reconciling East and West — just to bring off a functional collaboration between the Museum’s Costume Institute and Department of Asian Art is a colossal campaign. And that’s to say nothing of the structural challenges of their respective spaces. For one, the Chinese Galleries are hardly designed to house glass-encased costumes. Over in Costume it’s an easier rig, but overall designer Nathan Crowly has his work cut out for him.

The exhibition teases out theatricality where little exists. Surrounded with light, color, projections, music and high fashion, the Museum’s artifacts become part of a full-on sensory immersion. It’s one thing to see the blue-and-white porcelain pieces of the venerable Porcelain Room, and it’s quite another to see them alongside Li Xiaofeng’s colossal assemblage of blue-and-white porcelain in the shape of a dress or a wearable gown whose bodice is covered in porcelain shards courtesy of Sarah Burton for Alexander McQueen. And all this washed in atmospheric effects.

For Rossi the brief is to create an immersion within an immersion. As with his 2011 film Page One: Inside the New York Times, the reflected spaces bring you closeup and personal with professional passions, only here instead of the news cycle it’s the curatorial process. You feel the pressures mounting, just as Bolton does. “We used every cinematic device that we could to bring to life the curatorial vision of Andrew Bolton and others involved in this show,” Rossi told thalo.com prior to the film’s opening night screening at the Tribeca Film Festival. One example he gave concerns the scene where Bolton “is meticulously playing with the finishing touches of how an Alexander McQueen dress cascades on the floor,” as Rossi put it. “For the most part the pacing of the film is fairly brisk, but we stay for over 60 seconds here because we want people to have an immersive experience inside of that room and hopefully feel they exist in the space with the dress and the wallpaper.”

Essentially that hope is to capture Bolton’s own embroidery: early on the curator talks about the exhibition as a “fantasy” of China. Exciting, sure, but how much fantasy is too much? At one point Wintour worries lest the show “look like a Chinese restaurant.”

Her worries prove unfounded, as you see when First Monday unearths the full fruits of Bolton’s imagination. Just as the film pairs images and ideas, so too the exhibition lays out objects of art alongside the fashions they helped inspire. Both efforts highlight the dialogue that has historically flowed between the two cultures. In the room devoted to traditional Manchu robes, for example, one robe worn by Pu Yi, the last emperor of China, is arrayed across from a regal gown that Tom Ford did up in yellow silk satin and sequins during his last season at Yves Saint Laurent.

One of the pleasures of both Rossi’s film and Bolton’s show is the carousel of Hollywood and Chinese films flashing across the big screen. Sensuous and illuminating, these cinematic images initiate — or reinitiate — you in the history of Chinese costumes, just as they did such culturally promiscuous talents as John Galliano, Karl Lagerfeld or for that matter, Bolton. You come out of these sequences pledging to rewatch In the Mood for Love, by Wong Kar-Wai, who serves as artistic director of the exhibition. More tempting still is to track down Shanghai Express, Josef von Sternberg’s 1932 classic starring Anna May Wong.

A number of caveats come with the beguilements. If Wong was given stereotypical “Dragon Lady” and “Lotus Blossom” roles throughout her career, Bolton is mindful that a Colonialist and Orientalist gaze “could be interpreted as being racist.” For him, the show’s higher goal is to redraw the Western fascination with exotic China along more humanistic lines, as an intercultural flow of ideas and as a revered fount of influence.

Rossi hits his stride when he teases out the show’s conceptual challenges. A running motif of the film is fashion’s merits as an art form worthy of enshrining in a museum to start with. In a traditional institution such as the Met, the view of painting, drawing and sculpture as the be-all and end-all of higher visual expression is a notion that can only die hard if indeed it ever does. But Bolton believes that fashion, in its highest expression, meets the criteria to call it an art.

Should First Monday enter the canon? Whatever the verdict, Rossi deserves as much credit for what he did as for what he resisted. First Monday is neither precious nor pretentious, and certainly not arty in any owlish sense of the word. Whether you saw the exhibition or sat it out, mark your calendar for The First Monday in May.

Photo Credits:

1) Met curator Andrew Bolton puts final touches. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures

2) Met Gala co-chair Anna Wintour holds court. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures

3) Rihanna at the Met Gala. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures