"Byobu: The Grandeur of Japanese Screens" -- Interview with Curator Sadako Ohki

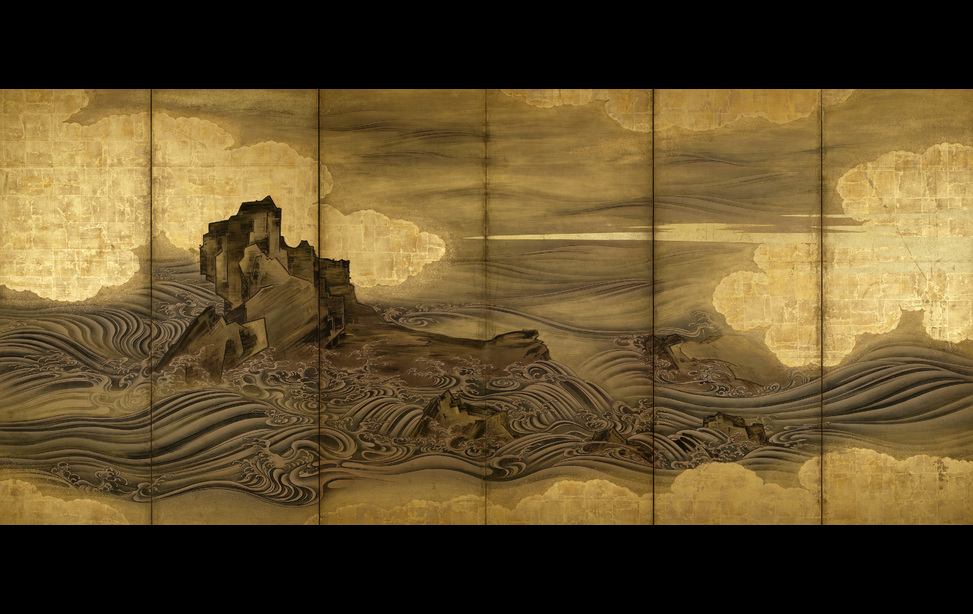

NEW HAVEN, CT --Although the Japanese term for folding screens, "byōbu," literally means "wind wall," Yale University Art Gallery's exhibition entitled Byōbu: The Grandeur of Japanese Screens brings a gust of rarefied air. Pomp, as the title hints, is part of the point here, as is scale (as seen in photo 1). There's a refreshing whiff of the literary in Byōbu's repertoire spanning five centuries of master Japanese painters and calligraphers. Add to that the social and environmental tinge of many of the featured pulp fictions, and a definite high-high zeitgeist wafts through this Downton Abbey of the rising sun.

The show opened on February 7, 2014, but enthusiasts of the art form will have to exercise Zen-like restraint to see its 38 component screens. Byōbu will unfurl in three consecutive tiers before Byōbu closes in July. The first tier, Tales and Poems in Byōbu, will remain on view through March 23. Next up is Brush and Ink in Byōbu (March 25 - May 11), followed by Nature and Celebration in Byōbu (May 13 - July 6). But what's five months relative to the more than three years that have gone into the exhibition's planning?

Visitors can expect to see mostly works from the 17th and 18th centuries, though some of the pieces date back to the 1550s and there's even one from the early 21st century. Adding another dimension to the appreciation of Japanese artifacts are historical objects ranging from pearly stirrups to a ceramic tea bowl 9 (as seen in photo 2).

Sadako Ohki, Japan Foundation Associate Curator of Japanese Art, curated the exhibition (as seen in photo 3). thalo.com reached Dr. Ohki in New Haven for a whirlwind verbal tour.

thalo: What was the original purpose of byōbu besides blocking drafts?

Sadako Ohki: More importantly they were needed to demarcate private space.

th: Gallery visitors may be most familiar with scenic byōbu, from films like Kurosawa's Ran or perhaps from anime. What's behind this tradition of sprawling vistas?

SO: In the 14th century, paper hinges were developed in Japan. Earlier screens had metal or wooden hinges connected by heavy cords. They were rather clumsy as well as heavy. The paper hinges allowed continuous images throughout multiple panels without a border on each panel. As the screens became lighter thanks to paper hinges, they also became portable. And when you folded them up, the ornamented sides were all protected and they were easily stored. Byōbu seen in Ran and many other films are the result of these paper hinges.

th: Where did the idea of ornamental Japanese screens come from?

SO: We have a record saying that screens came from the Korean kingdom of Silla during the 7th century, the Nara period.

th: Why did you select screens from the 16th century to the present for this exhibition?

SO: First of all, not many byōbu from earlier than the 16th century have survived. In the 1550s byōbu were exported to other countries, notably to Ming China. We have a rare example showing an exotic and restless landscape with birds such as the phoenix and the peafowl that will be shown in the third installation.

Secondly, there were many powerful warlords who had emerged to fill the vacuum of the weakened central authority surrounding a long period of civil war. These regional lords, or daimyō, typically built large castles. The inside space needed to have many demarcations. Not just the floating screens needed painting, but also the walls. So many of these warlords commissioned artists to make paintings on the walls as well as on the screens. Among them, three warlords in particular -- Nobunaga, Hideyoshi and Ieyasu -- built large castles. In the last three decades of the 16th century, Japan had what's known as the Azuchi-Momoyama period taking the name of the castles built by the first two warlords, respectively. By 1615 the country was unified by the third one, Tokugawa Ieyasu, and finally peace was brought to Japan. This period is called the Edo, or Tokugawa period.

th: Was all the gold leaf wielded as the equivalent of gangsta bling, to project a competitive edge?

SO: The use of gold leaf on byōbu in fact began earlier than the Azuchi-Momoyama period, by some religious groups, but their use was intensified when the warlords were vying with one another and trying to show off their power and wealth. Ostentatious displays of gold leaf continued in the 17th century. The luster of the gold or silver surfaces also helped brighten the typically dark castles and mansions.

Currently we're showing gilded byōbu illustrating the classical novel The Tale of Genji, Lady Murasaki Shikibu's story of courtly romance centering on Prince Genji. The Tale of Genji is from the Heian period (794 - 1185), but it was revived during the 17th century, when people could afford to enjoy a life of luxury and the vogue was to emulate courtly tradition. The surface of this particular byōbu is sprinkled with gold dust 9 (as seen in photo 4).

th: As Japan entered a period of peace and the warrior class settled down in the cities, how was this reflected in byōbu themes?

SO: After the civil war, the infrastructure of the artists and their skills remained. From 1615, the start of the Edo period controlled by the Tokugawa family, the peace lasted for 250 years until the Meiji Restoration of 1868 that led to the abolition of the feudal system. During the 17th century, at a time when there were no battles to be fought, the character of the samurai class changed. They had to learn to become more like civil servants.

The Tokugawa family, in order to buttress their legitimacy as rulers of the country, imposed Neo-Confucian philosophy emphasizing loyalty to the lord and filial piety as a strategy of controlling the samurai and commoners. Such historical narratives as Tale of the Heike and the Chinese book of parables Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety appeared, and they included some genre and battle scenes.

th: What were some of the popular themes for the rising merchant class that emerged towards the late 17th century -- who could afford the byōbu that had previously been the exclusive domain of the military and noble elite?

SO: Nouveau riche merchants from this time often commissioned byōbu reflecting a fantasy of escaping the city or displaying cultural activities. One of the screens in the Nature and Celebration in Byōbu group depicts an outdoor kabuki theater on the bank of the Kamo River in Kyoto -- or I should say, the dried riverbed of the Kamo. It's very much a genre scene. Many people are enjoying looking at the kabuki theater while they are eating, and there are even fist fights portrayed (as seen in photo 5).

Some of the temples and shrines also commissioned large byōbu paintings to record their festivals and activities. An example from our third installation is an unusual eight-panel byōbu, the Hie-Sannō Festival (as seen in photo 6). In our second installation, we're showing the Moonlight Bamboo screen from Yale's in-house collection. It's by Ike Taiga, a mid-18th-century painter and calligrapher whose works were admired and commissioned by all classes of people, from literati intellectuals and courtesans to top samurai lords and merchants.

th: Besides The Tale of Genji, is there a blockbuster saga that most Japanese contemporaries would have recognized?

SO: The other important tale that we're showing in some of the paintings is called The Tale of the Heike. That is the story of the rise and fall of a warrior family from the 12th century. It is based on the actual history, although with a lot of embellishment. We have two screens: one is on loan and the other is from our collection. The one from our collection is about the second-to-the-last battle between the two rival warrior families.

th: One of the most spectacular works is a pair of screens bursting with colorful flowers and leaves. What should we know about Japanese culture in order to understand this pastoral image?

SO: That's Flowering Cherry and Autumn Maple with Poem Slips, on loan from a private collection (as seen in photo 7). It is a pair of blossoming cherry trees on the right and maple leaves on the left. The work is from the 17th century. It has poetry from classical Japanese literature, a popular poetic genre called the waka. Waka consists of 31 syllables and was popular during the Heian period. It's written on special rectangular-shaped paper.

The cherry blossom and maple trees have their respectively themed poems -- 15 each. So altogether there are 30 poems in there. Tied to the cherry branches are small rectangular slips of Japanese paper. Each slip of paper contains one waka poem written calligraphically and it's fluttering in the wind. Some slips only show the partial poem. There are so many interesting works in the exhibition where it's very difficult to determine the artist's name, and this is one of them.

We have another pair of screens, Birds and Flowers of the 12 Months -- each month represented by a painting of a flower and a bird accompanied by a poem written on that theme. So each month has two poems written above the paintings. That pair of byōbu has altogether 24 poems.

th: What were some of the dominant schools of 17th and 18th centuries?

SO: The most famous one was called the Kanō school. The family started out in the 15th century and underwent urbanization. Around 1600 they moved their main branch from Kyoto to Edo, the new seat of the Tokugawa shogunate -- their chief patrons. Several examples of the Kanō works are included throughout the three installations. The Kanō developed a house style and trained their students in it. Although their visual manual was readily available for art teachers and students all over Japan, some of the Kanō methods were strictly secret, such as what pigments to use for a particular effect or what kind of ink to use and how much to dilute it.

Rival schools like the Hasegawa and the Kaiho appeared during the 17th century, and their works are also included in the second installation. The Rinpa school established by Ogata Kōrin in the early 17th century is represented in the current installation by an unusual two-panel wooden byōbu imbedded with precious metals and ceramics. It was made circa 1860 by one of the last members of the Rinpa school, Suzuki Shuitsu.

th: Was there one artist who was famous enough to be a household name?

SO: Kanō Tan'yū was one of the most famous ones among the Kanō school in the Edo period. In the third installation we have Birds and Flowers by Tan'yū at the ripe age of 71, and in the current installation the byōbu depicting 14 episodes from the first six chapters of The Tale of the Heike was most likely painted by the artists from Kanō Tan’yū's studio. The very first byōbu on your right after entering the current exhibition, Shell of the Locust -- depicting the scene of The Lady of the Locust (Utsusemi) from chapter three of The Tale of Genji -- is most likely painted by Tan'yū's father Kanō Takanobu, judging from the painting style.

th: What inspired you to include artifacts such as earthenware bowls and a pair of stirrups?

SO: It is to enrich the experience of viewing art. Right now we're showing this one black Raku tea bowl from the late 16th century, the Momoyama period. We put this bowl, entitled The Twilight by the Maples, next to the 17th-century painting of the gorgeous maple byōbu. If you look at the tea bowl straight on, the front section has a beautiful glittering effect like the glow at the end of the day. We placed the black bowl next to the maple painting to draw an association with the maple theme. When visitors see that the painting features an image of a curtain by the depicted maple, they may understand that a tea gathering is most likely taking place there. I tried to contextualize the painting and to let viewers imagine the time of day when people gather to have tea by the maples. The stirrups have this cherry blossom design, so I put them next to the paintings of the cherry blossoms so that visitors can imagine a horseback rider come to admire splendid cherry blossoms.

th: Why is the exhibition in three installations?

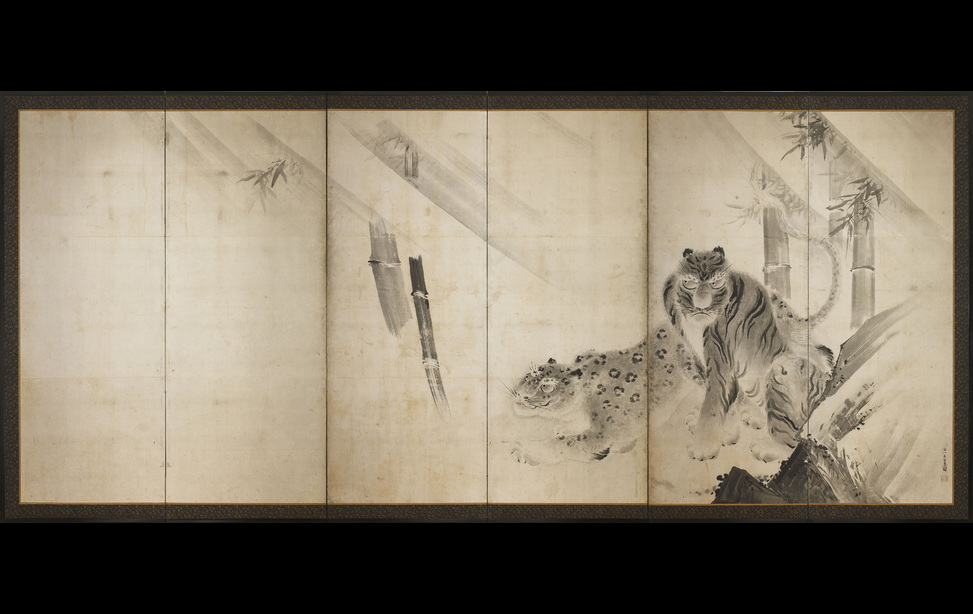

SO: The byōbu are large. In a 4,000-square-foot space, we can only show six pairs at a time because they take up so much room. The challenge was to figure out what kind of materials we could put together from works on loan and from our own collection. Almost three years ago I went to one of the collector's places, where I saw about 30 screens. I remember trying to see which among the best quality screens would work. We have to put everything together and make sense of what we have for an exhibition. That's how I came up with the three themes, beginning with Tales and Poems. The second group, Brush and Ink, shows the dynamic power of ink. Most of the selected byōbu were brushed only in ink, but some of the paper surfaces are covered with gold or silver, not necessarily just plain paper (as seen in photo 8). And as we said, the third installation, Nature and Celebration, has more of a genre and landscape theme.

th: Beyond the Gallery collection, where do the screens come from?

SO: It's a matter of the byōbu available to us here in this country because we are not borrowing byōbu from Japan. Most of the work is from this area -- from New England and New York. One is shipped from California, but that's an exception.

th: How much of the exhibition is from external sources?

SO: One third is ours and the others are on loan from six different collectors.

th: What's the current byōbu scene in Japan?

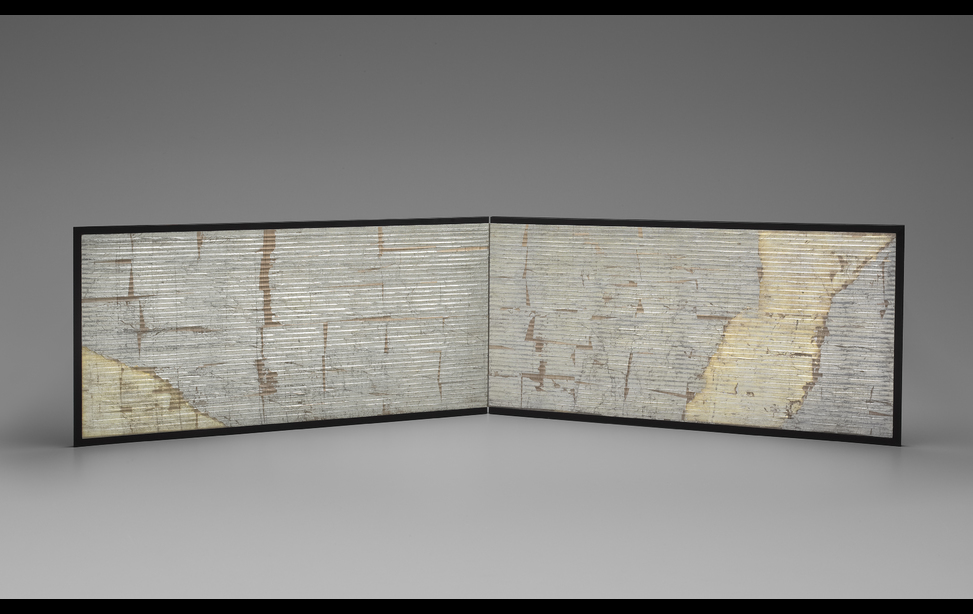

SO: There is a very famous artist named Maio Motoko. One of her works will be included in the third exhibition (as seen in photo 9). It's from 2004. She is making beautiful byōbu. Some of them are huge -- eight panels and eight feet tall. It's an incredible amount of work that she is producing. Her purview is not figurative painting, but rather more abstract designs.

th: What would you want to share with aspiring curators?

SO: Try to work with a very supportive team like the one I have at Yale University Art Gallery. Most of the exhibition cannot be done by myself at all. I have some ideas and I bring the research and scholarship, as we curators do. But we have to bring these into reality. If we don't have a good carpenter who would understand how to make even the platforms, there's no exhibition. Also there are the people in the graphics department who do a tremendous job of making the wall panels as well as the design of the pamphlets and brochures. And nothing can be done without such an excellent editorial team.

th: What insights would you like visitors to take away from this exhibition?

SO: In 2009 we had a big exhibition, Tea Culture of Japan, where we emphasized the very subdued aesthetics of the wabi tea ceremony. But this time I thought we'd show the diversity and complexity of Japanese language, art and literature. I hope that people will really be able to see that we have gorgeous, colorful paintings next to the calligraphy of waka written only in ink. The six waka are composed by women poets from the 9th to the 12th centuries and they were brushed by a male courtier from the early 17th century. So there are great contrasts even in this first installation. To view these three types of installations I'd really like to have visitors understand the multiplicity of Japanese aesthetics.

Photo credits:

Photo 1: Attributed to Hasegawa Tōgaku, "Waves and Rocks," Momoyama period, early 17th century. Right screen from a pair of six-panel folding screens: ink and gold on paper with sections covered with gold foil. Private Collection. Photo courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery.

Kyoto Kano School, "Tale of Genji," Edo period, ca. 1625–50. Right screen from a pair of six-panel folding screens: ink, color, and gold leaf on gold-flecked paper. Yale University Art Gallery, Edward H. Dunlap, B.A. 1934. Photo courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery.

Photo 2: Kitamura Tatsuo, Black Tea Bowl with Dragon, Heisei era, ca. 2000. Lacquer on wood. Collection of Peggy and Richard M. Danziger, LL.B. 1963. Photo courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery.

Photo 3: Sadako Ohki explaining "Byōbu: The Grandeur of Japanese Screens" to a group of visitors, courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery. Photo courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery.

Photo 4: Kyoto Kano School, Tale of Genji, Edo period, ca. 1625–50. Right screen from a pair of six-panel folding screens: ink, color, and gold leaf on gold-flecked paper. Yale University Art Gallery, Edward H. Dunlap, B.A. 1934, Fund. Photo courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery.

Photo 5: Early Kabuki, Japanese, Edo period, early 17th century. Six-panel folding screen: ink and color on paper. Lent by Rosemarie and Leighton R. Longhi, B.A. 1967. Photo courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery.

Photo 6: Hie-Sannō Festival, Momoyama period, 1590s. Eight-panel folding screen: ink, color, and gold pigment on gold-foiled paper. Lent by Rosemarie and Leighton R. Longhi, B.A. 1967. Photo courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery.

Photo 7: "Flowering Cherry and Autumn Maple with Poem Slips," Japanese, Edo period (1615– 1868), 17th century. Pair of six-panel folding screens: ink, mineral color, gold, and silver on paper. Collection of Peggy and Richard M. Danziger, ll.b. 1963. Photo courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery.

Photo 8: Kaihō Yūsetsu, "Dragon and Tiger with Leopard," Edo period, mid-17th century. Pair of six-panel folding screens: ink on paper. Lent by Rosemarie and Leighton R. Longhi, B.A. 1967. Photo courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery.

Photo 9: Maio Motoko (Japanese, born 1948), "Wind Screen for Tea Brazier," Heisei era (1989– present), 2004. Two-panel folding screen: washi paper with metallic foil, and backing paper treated with persimmon juice. Collection of Peggy and Richard M. Danziger, ll.b. 1963. Photo courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery.