20th Century Art Movements: Cubism

The late 19th Century was a period of tremendous technological development, as modern inventions like cameras, automobiles, airplanes, and telephones strengthened the influence of the Industrial Revolution in Europe. Increasingly, representational art became a limited means of expression for certain artists who sought to reconcile their fears and emotions over industrialization and uncertain times by embracing new art forms.

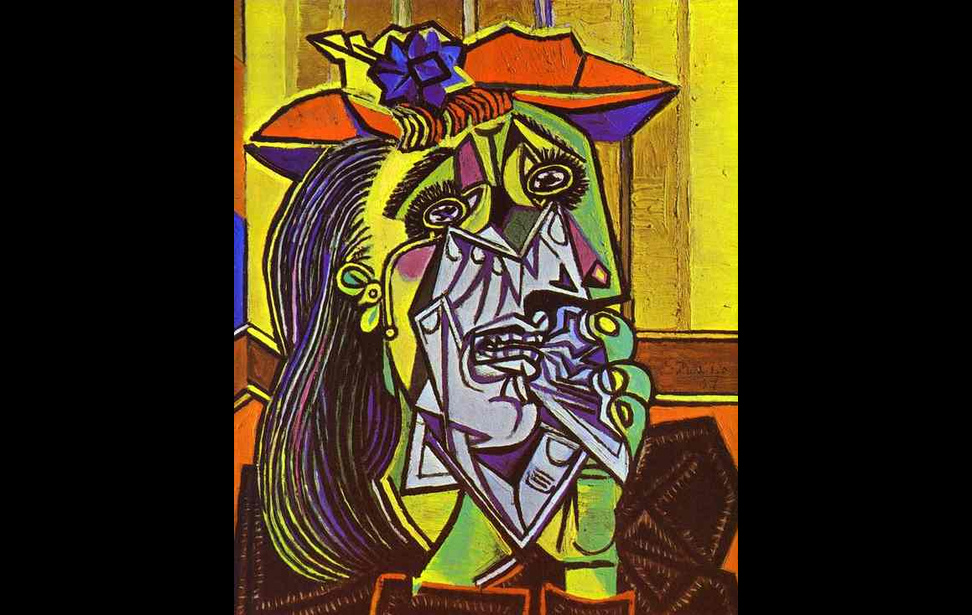

Cubism is a 20th Century art movement born under these conditions, inspired by Paul Cezanne’s later works in exploring dimensional realism, conceptual reality, and geometric forms (as seen in photo 1) with no regard for perspective or Renaissance imagery previously held as artistic ideals.

Cezanne led artists away from French Impressionism’s restrictive use of color, lighting and natural landscapes toward vibrant, experimental compositions with flat, converging planes. Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso were among the first to distance themselves from the confines of traditional painterly fundamentals with a sense of artistic freedom.

Along with French artist Georges Braque, Picasso became a figurehead for the Cubist aesthetic by breaking art objects down into simple geometric shapes sandwiched between multiple abstract planes in a single composition (as seen in photo 2).

Early Influence

Braque’s iconic painting of a fishing village near Marsailles was most responsible for Cubism’s initial attention. The enigmatic landscape Houses at L’Estaque, first seen at a 1908 Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler Gallery exhibition after being refused by the Salon d’Automne, was ridiculed by critic Louis Vauxcelles, who commented that Braque’s painting reduced all painterly elements to “geometric schemas and cubes.”

Picasso followed Braque’s lead in 1907 with another landmark Cubist painting, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, and the two became friends after being introduced by Guillaume Apollinaire, an influential poet and art critic within the Paris art scene.

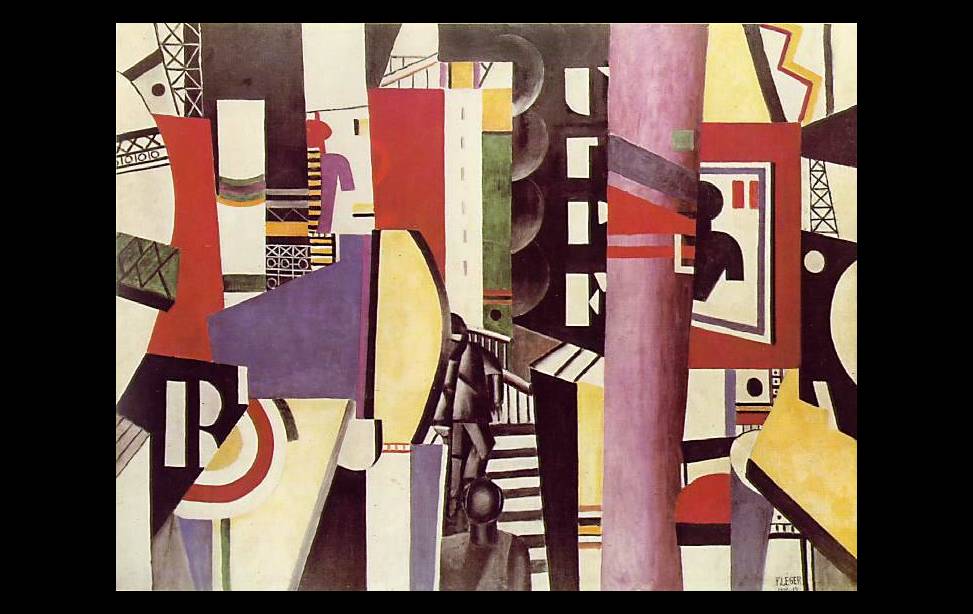

Their collaborative leadership soon attracted the interest of other important French and Spanish artists like Juan Gris, Fernand Leger and Robert Delaunay. Cubism’s controversy supplied an infectious influence for young talents, often provoking sharp criticism and political dissent among critics, artists, and patrons alike. Leger’s unique style of cubist art is seen in photo 3.

Exhibitions at the Salon des Independents in 1911 and the Salon d’Automne in 1912 marked the official beginning of the Cubist movement, though art dealers initially discouraged those they represented from showing works in public.

Theory and Impact

Cubism became a springboard for challenging art’s physical and representational laws, long considered sacred. Proponents turned a blind eye to linear and atmospheric perspective, focusing instead on a gritty, vibrant, primitive world imagined in the mind, shattering the illusion of balanced structure and well-ordered modeling so commonly seen in art of the previous century.

Cubists rallied against social, economic, and industrial advances as a threat to art itself. In their opinion, an industrialized society that fathered mass production, poster art, and inexpensive printing techniques changed the Paris art scene seemingly overnight. Their collective response was to describe the world around them using basic formalist elements like color, line, and shape within every composition.

Cubism progressed through two short but distinct phases. Analytic Cubism developed Picasso’s moody, monochrome, figurative studies of geometric forms with multiple viewpoints beginning in 1910.

Two years later, Synthetic Cubism combined collage within the Cubist framework, as artists expanded themes using brighter colors, real objects, graphics, and textures to further deconstruct three-dimensional space. Photo 4, The Sunblind by Juan Gris, shows how the artist incorporated a real copy of a local newspaper, Le Socialiste, into his painting.

Cubism Declines

World War I divided artists among nationalist concerns, and Cubism steadily declined in popularity after 1920, relinquishing avant-garde status to offspring art movements like Abstract Expressionism and Surrealism that further developed abstract themes.

Most artists connected with the movement faded into obscurity in years to come. Only Picasso, who endured Nazi occupation in France during the 1940’s, remained true to Cubism’s ideal until his death in 1973 at the age of 91, fathering four children and inspiring numerous prodigal artists influenced by his work.

Photo Credits:

Photo 1 - The Bathers by Paul Cezanne (http://simple.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Paul_C%C3%A9zanne_048.jpg)

Photo 2 - Weeping Woman (1937) by Pablo Picasso (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Picasso_The_Weeping_Woman_Tate_identifier_T05010_10.jpg)

Photo 3 - The City (1919) by Fernand Leger (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Legar-_The_City_1919.jpg)

Photo 4 - The Sunblind by Juan Gris (http://www.wikipaintings.org/en/juan-gris/the-sunblind-1914)

References:

Moffat, C.A. The Art History Archive - Art Movements: Cubism. Available at: http://bit.ly/1lKw3il (2009).

Staff Editors. Cubism – The First Style of Abstract Art. Available at: http://bit.ly/1cVpq4G (2014).