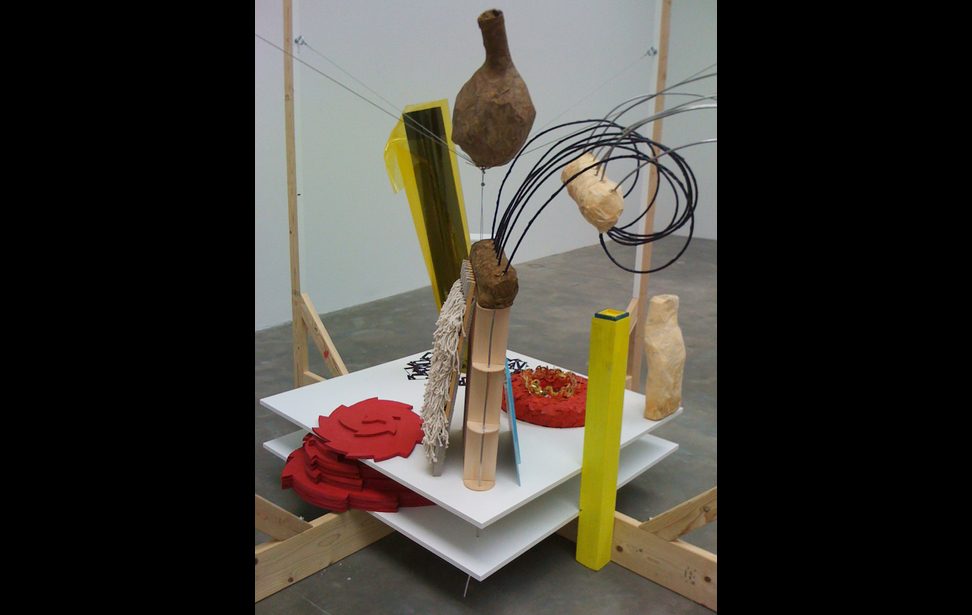

Richard Tuttle: The Opulence of Everyday Things

Paper clips, styrofoam, feathers, Saran wrap, balloons, bubble wrap, cardboard, cotton string, wingnuts and plywood – this is a small list of what Richard Tuttle has been using in his quest to represent what cannot be seen. Sound mystical? That's the idea behind "What's the Wind," an exhibition of recent sculptures at Pace Gallery in New York. Called Systems, these six free-standing pieces suspend delicately crafted, amalgamate constructions so loosely joined it's difficult to even call them objects (as seen in photos 1 - 4). They hover above plywood platforms and smaller sculptured forms made from materials so familiar to us as to be uninteresting in any other context. A piece of egg crate foam?

This is a little like making art out of nothing. Tuttle isn't afraid of nothingness; in fact, what is not there is part of what makes his work what it is. Supporting critics such as Art in America's Richard Kalina refer to this as the "dematerialization" of the object. For example, early works from the 1960's called "Constructed Relief Paintings" were made from cut canvas without use of stretcher bars or a frame. The fabric was cut, modestly hemmed, monochromatically dyed and pinned to the wall or just set on the floor arbitrarily. Other works were made of cut white paper pasted flat against a white wall, almost imperceptible in certain lighting conditions.

Far reaching it was, at least in the mid 1960s. Within ten years he was given a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum, which was met with skepticism and derision in the media. New York Times critic Hilton Kramer wrote that instead of less is more, "so far as art is concerned, less has never been less than this." Marcia Tucker, the curator of the show, was eventually fired.

Tuttle was a heretic, a naysayer who found delight in what might be the mirror opposite of the art world's current values. Large abstract paintings represented America's global achievement in Abstract Expressionism. Tuttle's work was small. Minimalism became the art world's official answer to Expressionism, swapping out old existential bravado for anal-retentive, rule-based theorizing. Here comes Tuttle with offhanded free play.

Tuttle is now one of the most influential artists today, with an exhibition record nearing 300 solo shows. He's considered a pre-eminent post-Minimalist, but historical categories aren't as interesting as material ones. Are those cut, dyed and sewn canvases really paintings? Or are they flat, practically weightless, sculptures? The philosophical foundations of painting and sculpture have been subject to much academic handwringing. For Tuttle, the difference is just one of method, a couples to make something that didn't exist before. This approach has been provocatively explored at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

As is the case with all his work, the pieces in "What's the Wind" give the viewer little in the way of instruction on how to view them, much less what they are. More opulent and materially diverse than his early work, these Systems draw upon and carry out Tuttle's 50 year mission to see the importance of looking at ordinary objects –and by extension the world– without direction or utilitarian purpose. This is achieved, in part, by taking useful items like Saran wrap and sheet metal and rendering them uselessly beautiful in their own independently crafted worlds.

All photos courtesy of Rob Reed.