Istanbul Design Biennial: Design Examined

ISTANBUL, TURKEY – A black metal prison door opens onto a long, dimly lit corridor with high, gray walls. In the background is a constant barrage of ominous-sounding noises: rumbling, scraping, drilling, demolition, women screaming. This is the setting for “Musibet” (“Calamity”), currently on display at the Istanbul Modern and part of the ambitious first-ever Istanbul Design Biennial, which runs through December 12.

In recent years, Turkey’s largest city has become an increasingly significant destination for arts and culture, particularly since its stint as European Capital of Culture in 2010. The visual-art-oriented Istanbul Biennial, running since 1987, is well regarded by international art critics. Organized by the same institution (IKSV, the Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts), the newly inaugurated Istanbul Design Biennial aims to encourage similar interest in design while further strengthening the city’s presence on the international arts scene. Conceived under the overarching theme of “Imperfection,” two complementary exhibitions showcase work in various fields of design by nearly 300 designers, artists and architects from 46 countries.

Curated by Aga Khan-award-winning Turkish architect Emre Arolat, “Musibet” features around 30 projects ranging from video and multimedia works to photography, sound installations and fashion (as seen in photos 1 -2). The disturbing prison-like entryway sets the stage for a critical examination of urban design and architecture throughout. Many works chronicle the disintegration of the historical fabric of Istanbul, a sprawling metropolis of some 15 million where old neighborhoods are being torn down and new architectural schemes seem to emerge daily.

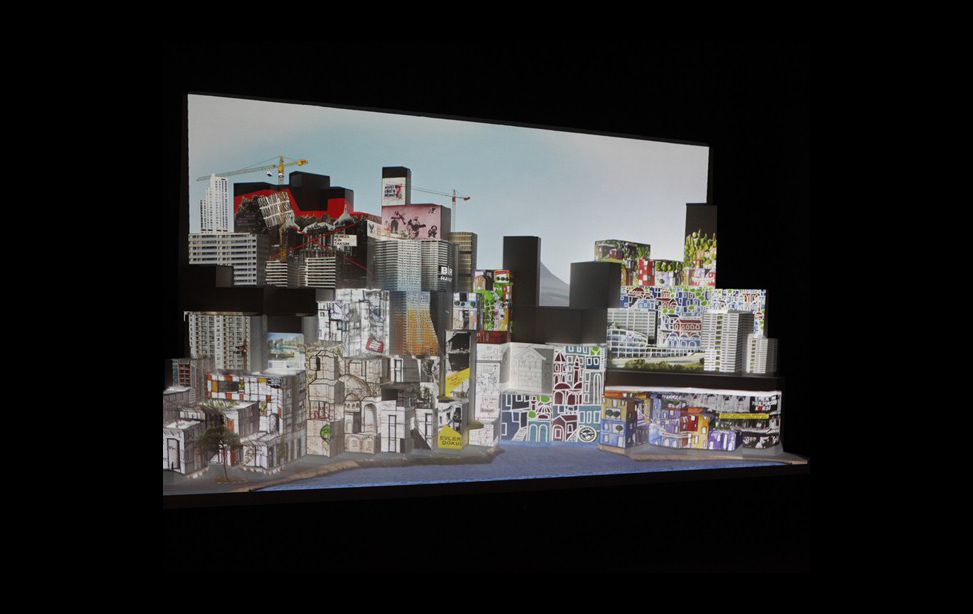

The ongoing tug of war over the city’s redevelopment is powerfully illustrated in “Istanbul-O-Matic,” an interactive video game (as seen in photos 3 – 5) by Turkish architects Cem Kozar and Isil Unal. Visitors step onto pads representing different actors (politicians, investors, starchitects, NGOs, regular citizens, etc.), triggering myriad combinations of images – collapsing buildings, skyscrapers shooting upwards, cranes balanced over historic monuments – that are projected onto a 3-D screen simulating Istanbul’s skyline.

Also memorable is Ozden Demir’s poignant short film “Net 17950,” which shows a man building a shack amidst an empty construction site from furniture and objects salvaged from bulldozed homes. Though Istanbul serves as the primary case study for “Musibet,” other cities, including Los Angeles, Shanghai and Dubai, are also examined. Collectively, the exhibits draw attention to the causes and perils of urban transformation not only in Istanbul, but by extension in all modern metropolises.

Running in parallel to Arolat’s exhibition, “Adhocracy,” curated by Joseph Grima, editor of Italian architecture/design magazine Domus, offers a more optimistic view. The title, a neologism coined from the term “ad hoc,” proposes a bottom-up approach that is opposite to top-down bureaucracy. “Adhocracy” – which Grima sums up in his curatorial notes as “an exhibit about people who make things” – is a sort of open laboratory for innovative design solutions and ideas.

In more than 60 exhibits spread out over five floors of a restored historic building, “Adhocracy” explores the possibilities offered by the DIY movement and the democratization of design through collaborative platforms. Some models have the offbeat, experimental feel of science fair projects, like German artist Annika Frye’s “Improvisation Machine,” which creates one-of-a-kind ceramic pieces (as seen in photo 6), or a mobile street cart that does 3-D printing of faux design objects (as seen in photo 7). Other displays demonstrate the application of open sourcing to areas as diverse as building and farm equipment (as seen in photo 8), constructing children’s toys, urban mapping, audio sampling and wildlife tracking.

Several works address social issues, such as Pedro Reyes’s inspiring “Imagine,” a fully functional orchestra the Mexican artist has created from upcycled firearms and other weapons (as seen in photo 9). British writer and technologist James Bridle’s “Drone Shadow” – a semi-permanent piece of sidewalk art located across the street from the exhibition venue – is a subtle commentary on the pervasiveness of surveillance in the current era.

Many biennials around the world seem to reinforce the idea of art and design as the rarefied domain of the so-called “creative class.” Refreshingly, the first Istanbul Design Biennial embraces a more accessible approach, emphasizing the relevance of design as something that affects every aspect of our daily lives.

All photos courtesy of Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts