Maurizio Cattelan Turns The Guggenheim Inside Out

NEW YORK, NY - For his first solo exhibition, Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan hung a small, plastic sign outside a locked gallery that said “Torno Subito” or Be Back Soon. The sign remained there, and the gallery remained locked, for the duration of the show. Four years later, at the Venice Biennial, Cattelan sold his allotted space to an agency that put up a billboard in its place, and once, for an exhibition in Amsterdam, he stole another artist’s work from a nearby gallery and tried to pass it off as his own.

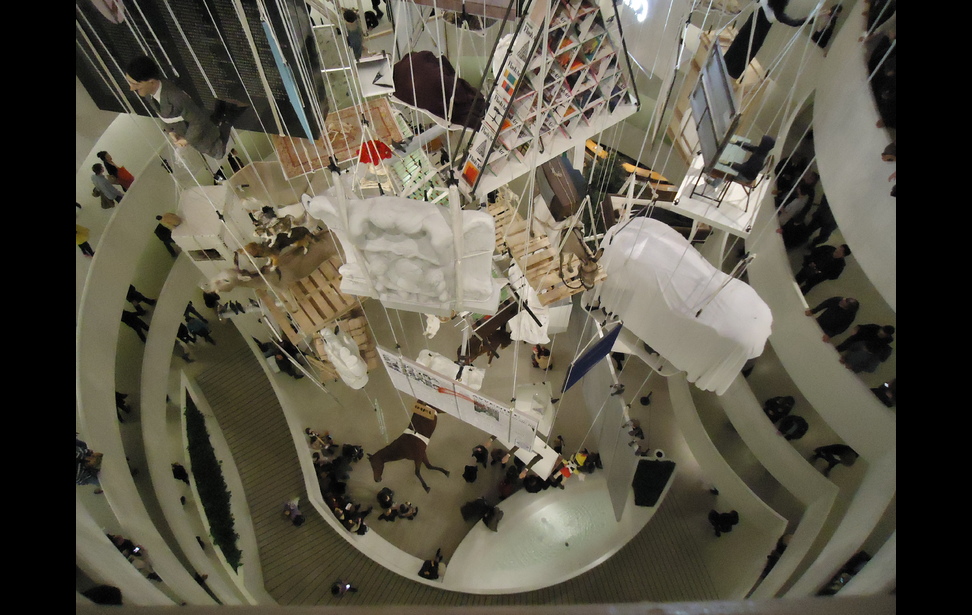

Surprisingly, the artist has managed to produce a significant body of his own work over the past two decades, nearly all of which (123 pieces to be exact) were exhibited in a retrospective show at the Guggenheim Museum in New York from November until January. Fortunately for all who waited in line with me to see Maurizio Cattelan: All on a “pay-what-you-wish” Saturday night, the museum’s doors were not locked. The Be Back Soon sign was hung, however, along with the billboard from the Venice Biennial and a potpourri of other curious objects—taxidermied animals, an elongated foosball table, a wax effigy of the Pope struck down by a meteor—from the museum’s rotunda ceiling.

Unlike any show in the Guggenheim’s history, Maurizio Cattelan: All occupied what is usually a void in the center of the museum’s spiraling floors, leaving the walls along the peripheries blank. With all of the works suspended by cables (an extraordinary feat from an engineering standpoint) the configuration has been likened to a mobile, a chandelier, a mass execution (as seen in Photos 1 - 5). Whatever the comparison, one of the effects of the installation was that each work could be viewed from seemingly limitless perspectives. And if one were to ascend or descend the spiral while focusing on an individual work, the pieces surrounding that work would always change in relation to it; the contexts shift along with the viewer.

Cattelan’s works are notoriously humorous and provocative. He enjoys upending socially accepted hierarchies, challenging the authority of lauded political and religious figures, and often takes jabs at the art world itself. In the case of this exhibition, the Guggenheim might be said to have welcomed the jab, perhaps even jabbed itself. Traditionally, the purpose of a retrospective is to display the whole of an artist’s work in chronological order, giving a comprehensive overview of its evolution. As Chief Curator Nancy Spector put it, Cattelan’s exhibition “lampoons the idea of comprehensiveness.” There was no discernable logic governing the work’s arrangement, and, unless viewers were willing to refer constantly to the show’s extensive catalogue, all of the dates and titles remained a mystery.

The exhibition has been criticized for severing Cattelan’s works from their intended contexts, compromising their original meanings. But if you look at the show as a whole, a work of art unto itself rather than a haphazard assortment of parts, the effect is one of palpable transcendence. Likewise, when people come together in large numbers they become a crowd, an entity that both includes and transcends its constituting parts. In his radical rethinking of the museum’s space, Cattelan ensured that viewers would not only see his work but also see each other, knowing that they too were being seen against the walls where the art usually hangs. In effect, he had turned the museum inside out.

The night I attended Maurizio Cattelan: All, the Guggenheim was packed. Even if we didn’t know each other’s personal histories, our shared purpose and our shared willingness to wait in line, in the cold, to see something that may or may not be a big joke, felt like it must mean something. I got the sense that there was something remarkable about the presence of so many people together in that space, in that moment of history, in that quizzical and inimitable configuration.

Photos courtesy of Ellen Brown