Ben Woolfitt: Mixing Art and Commerce

By Laura Blum

Of all the romantic images in cultural history, that of the starving, bohemian artist is surely the stubbornist. But Ben Woolfitt is no example. He's keeping both of his ears. The gifted creator of paintings and drawings has mastered the entrepreneurial arts. Or is it the other way around? Having crunched numbers professionally since age 13, Canadian business mogul Woolfitt has, you might say, supported his creative habit. Either way, he's the very portrait of a self-made man (as seen in photo 1).

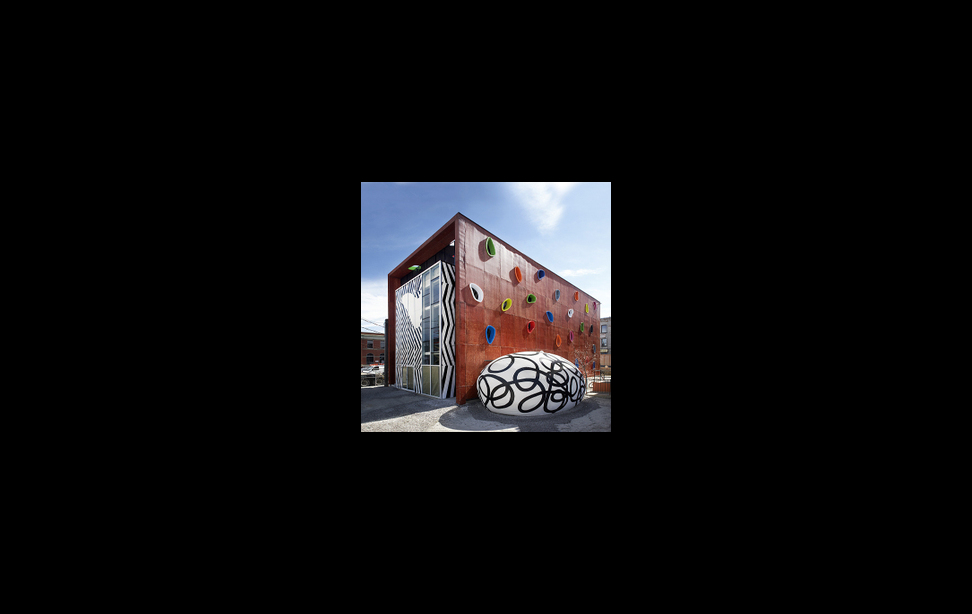

Woolfitt's Art Supplies, the ma-and-pa retail outfit he launched in Toronto in 1978, quickly caught on. By the 80's it was a thriving international company with prime markets in Europe and Asia. Woolfitt's evolved out of the art supply dealings that helped him pay his bills beginning in 1973, a year after he'd founded and run another establishment: an art school called Woolfitt’s School of Contemporary Painting, where he also taught until folding it in 1979. Today, two years after shuttering Woolfitt's Art Supplies, the left-and-right-brained 69 year old has his sights on a new art-themed venture. Woolfitt is putting a cool million towards the foundation and museum he's setting up under the name the modern.toronto. It's as much a tribute to his aesthetic passions as to the real estate savvy that has long anchored them (as seen in photo 2).

There's a definite symbiosis to his commerical and artistic success. "Numbers create order and painting creates chaos," Woolfitt told me on a raw April afternoon in Manhattan, where he now splits his time with Toronto. His East Village studio and apartment make a strong case for "establishing a framework for the chaos to exist." The walls of both are lined with the graphite drawings and gelato-hued acrylics that have earned him the acclaim and friendship of critics from Ken Carpenter to Kenworth W. Moffett.

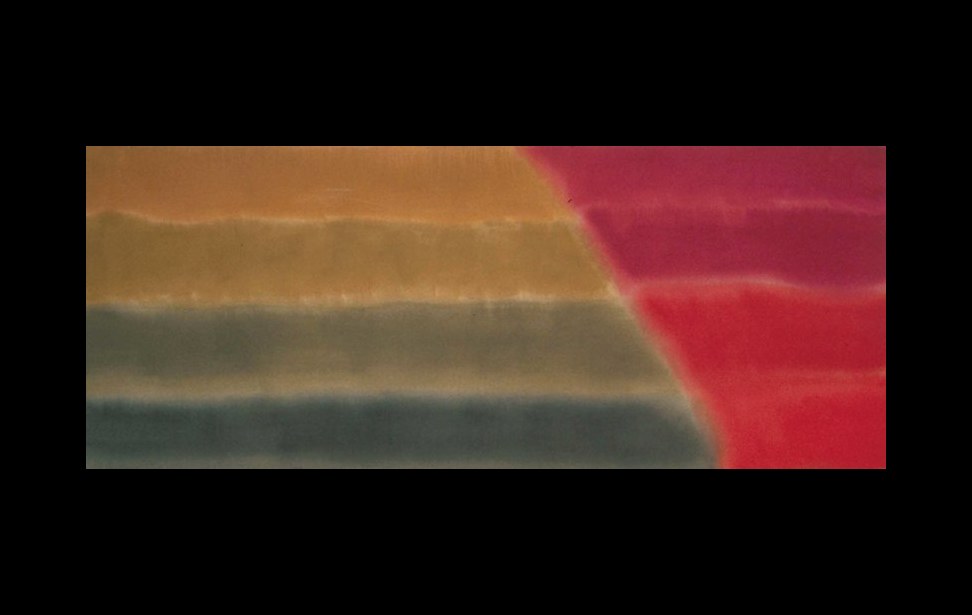

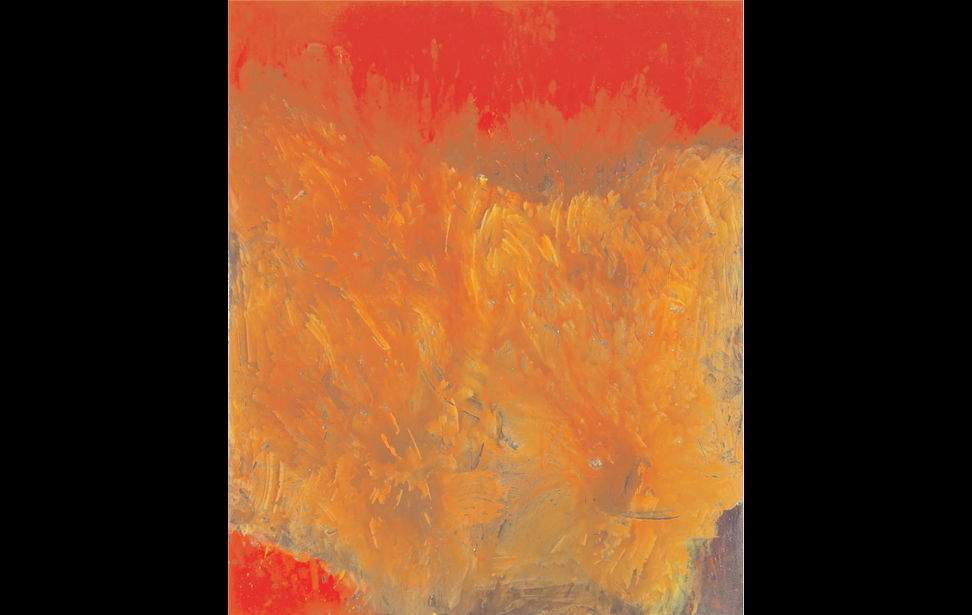

One that especially caught my eye stretches from floor to ceiling in the tony living room facing the immaculate kitchen. On its surface, the painting suggests lavender trees at dusk. But study its topography and see that what's layered on the monumental canvas is a rich glaze of acrylic gel (as seen in photo 3). Woolfitt's romance with this glossy medium dates back to the late 80's, when he experimented around, and saw that acrylics yielded a deeper, more sensuous color than he thought he could get from oils. Poring over the ambered reds and yellows of several works-in-progress laid horizontally in his studio, I could imagine dipping a finger into the translucent bog and tasting Eden's forbidden fruits (as seen in photo 4). Each tableau gets between 90 to 150 coats of paint, a process that can take up to three or four months. Unlike the precise calculus he brings to his commercial transactions, Woolfitt lets his gut tell him when a piece is finished.

Nothing about the artist's demeanor says gray suits, or for that matter, blue-chip valuation. Woolfitt's psychological bent and a flair for storytelling, joined with his penchant for black turtlenecks, hint at a sensitive streak. The caffeine he nursed during my visit could only have been because he likes the taste of coffee and not for any need of energy reinforcement or entrée to the primordial self. It's hard to resist connecting his many-layered paintings and serenely melancholic drawings to his complex persona. He cops to having a curious relationship with perfectionism, and despite his easy warmth, there's a lingering angst, which sparks and focuses his ambitions. It’s perhaps the legacy of what he calls "traumatic incidents" growing up. It didn't help that his surroundings lacked fertile ground for museums and galleries, among other hothouses to slake his cultural thirsts.

Woolfit began dabbling in art as a boy, on the family's Saskatchewan's farm. Woolfitt père was a rancher who later managed credit unions, and his mother gardened and delivered the farm goods when she wasn't engraving metal trays or tooling decorative leather. Beyond such maternal tinkerings, Woolfitt fils had the British branch of the family as creative role models, from stage actor Sir Donald Woolfitt to photographer Adam Woolfitt. But any hope of living up to his artistic pedigree meant getting out of Dodge.

In 1965, Woolfitt left the Western hills for Toronto's York University. Soon after, Carpenter, who was then a dean at the school, showed him an El Greco painting. "The temperature of my body shifted," Woolfitt recalled a half-century later. "I just knew that something had changed in my life." The following year he made a museum hejira to New York City. In MoMA and other modern art shines, he discovered the works of Mark Rothko, Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski and other leading Color Field painters of the era. The encounter would prove fateful. In 1968 he resolved to become an artist. Woolfitt partly credits an Ellsworth Kelly lithograph that he bought and tried to draw. "This is actually much more complex than I thought," he now remembered realizing. The gauntlet was unceremoniously thrown down.

Woolfitt's art straddles two main movements: modernism, which drank from the minimalist and abstract expressionist punch; and post-modernism, pushing the aesthetic boundaries to embrace literary and other critical elements. For his first foray into modernism, he improvised a method involving washes of water and spongings that produced diffuse color bands not unlike auroras. The technique marked his debut solo show at York in 1969 and flared up in subsequent series (as seen in photo 5).

Yet for all his fascination with external aesthetics, Woolfitt picked up a tool in the late 60's that would draw out his psyche. The thrashing ground was Therafields, a psychoanalytic community that attracted creative sorts and lost souls. "It helped me stabilize myself and understand my inner workings," said Woolfitt. That's more than could be said for the tranquilizers he had begun taking in his teens. Therafields gave him access to his unconscious mind and had what he described as a "tremendous influence" on his life and art. "It taught me a lot about how to look at paintings, which are essentially statements of self," Woolfitt reflected. Gaining an internal track allowed him to work out his mental anguish through painting and drawing while also granting him the emotional wherewithal to finesse more mundane pursuits. "Without the work that I did at Therafields, I couldn't have managed a business, particularly not an international one," he said.

Another concrete result of his Therafield association was the group studio he helped midwife for some 20 fellow participants. Among them was poet bp Nichol, featuring creative workshops led by such analysts as poets bpNichol, who became a close personal friend. During these immersive weekends of painting, drawing and talking, Woolfitt not only progressed as an artist, he also grappled with the nature of the "artist's relationship to his work." For Woolfitt's next series he began lingering considerably longer than the "one-shot paintings" that had informed his previous modus operandi. His new way of laying down color was by spraying paint around stenciled shapes. Within a year he would swap the stencils for a system of brushing shapes, often in gold paint, that were faintly suggestive of letters or symbols, if not specimens found under a microscope (as seen in photo 6). But Woolfitt is not one for Where's Waldo? "I always tried to stay away from referential marks," he said with a firm nod.

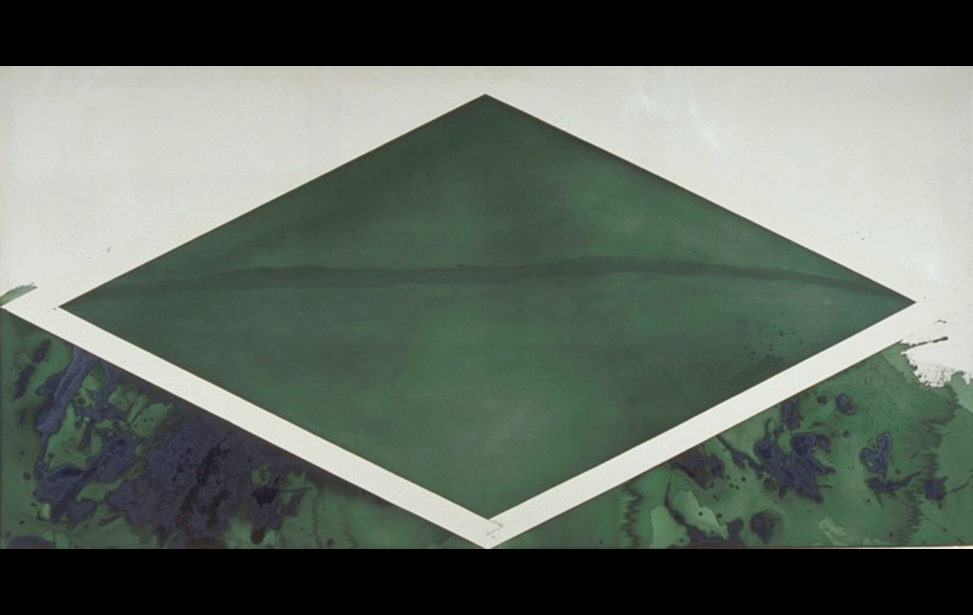

In the mid-70s Woolfitt mounted a series featuring diamond shapes and a pronounced fascination with layering. Painted with colored stains, the canvases were washed down with as much as 10 to 20 gallons of water. If the sky were green -- and created with a geometry kit -- it might resemble the dreamy expanse of emerald wisps in one work that especially popped for me. "Untitled" Green Diamond bears out the artist's budding love affair with surface modulation (as seen in photo 7). To achieve the painting's cloud-like affect, Woolfitt used rags, as he often does. Asked if the technique allowed him to purge his feelings, he conceded, "It's like an emotional washing."

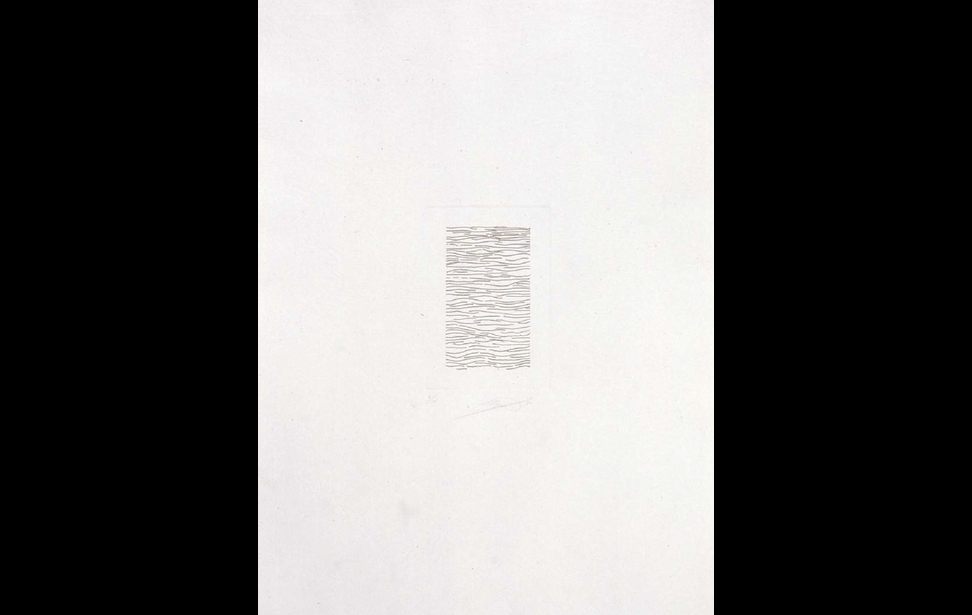

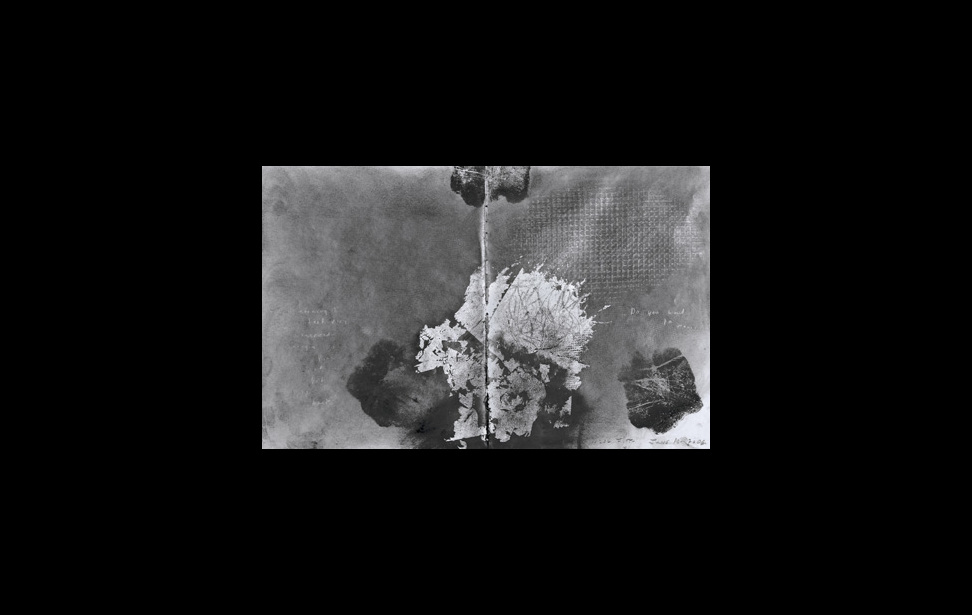

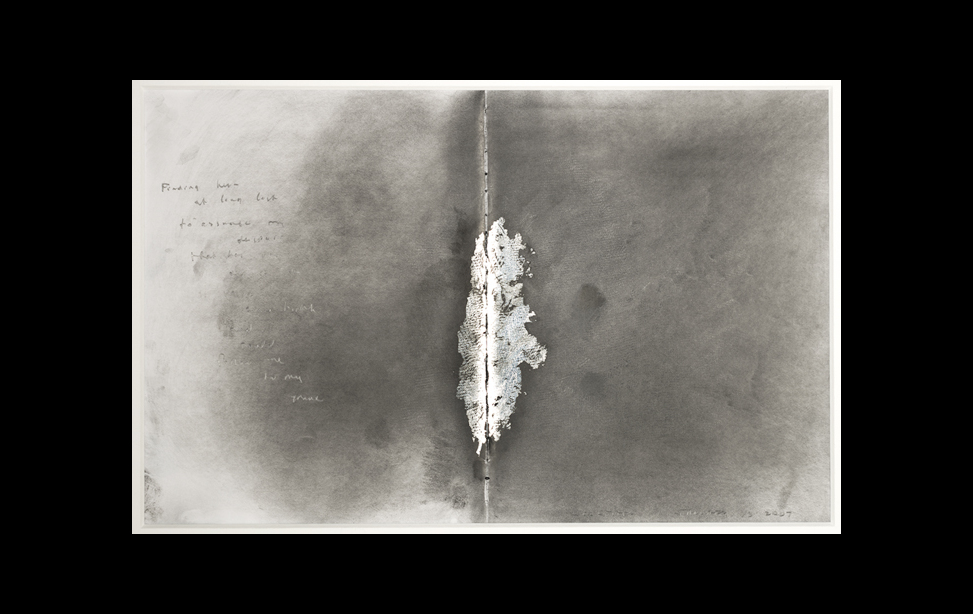

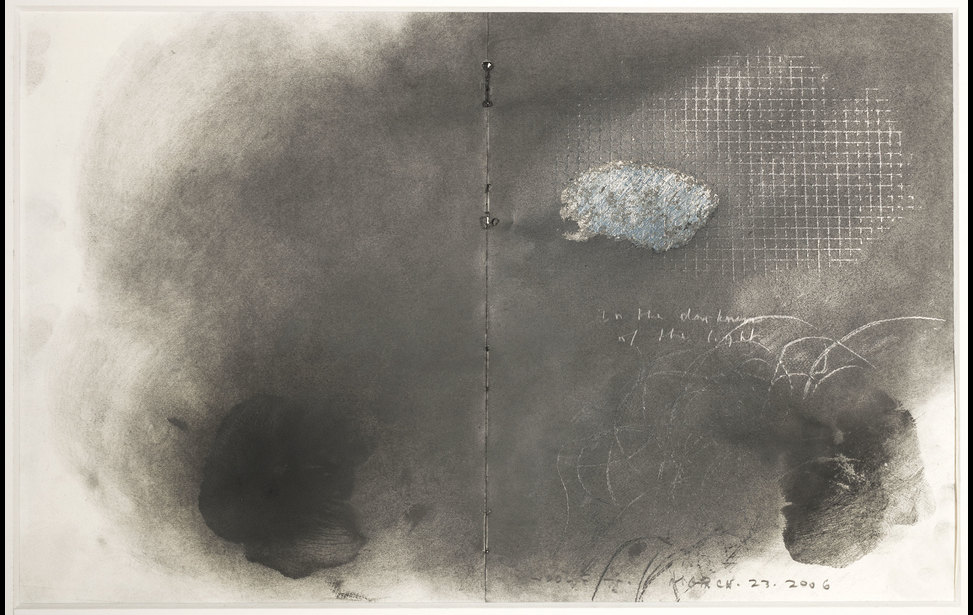

Following a fallow patch in the late 70's, the next big watershed coincided with the growth of his art emporium. Around 1980 Woolfitt began using the same metal leaf in his work that he was using to make picture frames. More dramatically, though, was the death of his mother that year. He developed a series of ten etchings inspired by his feeling of loss and evoking themes of femininity and eroticism. One of the etchings -- "Number 3" (1981) -- was intended as "a last letter to her," as he put it (as seen in photo 8). "It was likely meaningful to me because my tie to my mother was the one thing that made me feel safe," Woolfitt confided. Another tragic loss came with the death of Woolfitt's sister Shirley, in 1996. It was around then that he began adding text to his watercolor and ink works on waxed paper. "I regarded the drawings like diaries," he explained, noting that he was on the road a great deal during that period and that he found a degree of catharsis in expressing his sadness and anxiety (and joy) on the pages of his notebooks. Shedding the artistic detachment of his modernist work, with its stress on the aesthetic medium, he now explored a post-modernist mode, mixing image with writing and probing issues of identity and personal narrative. Some of the scrawls are directly confessional, as in: "This morning I feel very reserved." Others run to the more poetic, even cryptic. Consider: "Finding her at long last to assuage my despair..." or: "In the darkness of the light." Doubling as titles, the texts continue to rear up in his drawings still today (as seen in photos 9-11).

So do the grids that he had been toying with prior to his father's death in 1999, but which became something of a trademark ever since. Frotted over wire mesh in blacks and soft grays, these lattices hint at the structure that Woolfitt's balancing act seems to thrive on. Even paintings that appear to detonate reference the utility of a steady mooring. "When I'm pushed in too many directions, my painting becomes more conservative," he noted, adding, "When I'm organized, the painting opens up and becomes more complex." Prime examples are found in both the Water and Oceanic series of 2003 and in a roiling dynamo of 2013 vintage that jolts to mind J.M. Turner -- and that Woolfitt has tagged as one of his best works. (as seen in photos 12-14).It's only fitting that Woolfitt's process would take paradox as a rule. His drawings themselves exude an air of Zen; the silver grace notes, the spare compositions, the organic textures and the personal revelations all come together in an aesthetic that brings to mind Japanese spiritual traditions. Small wonder that Woolfitt has a soft spot for Japan. His work has been shown in that country, which he initially got to know while making the rounds of paper mills and paper makers for his art supply business.

By no means was Japan his only paper source. He also imported from Quebec, Massachusetts, the Netherlands, England and France. "We used to do a lot of custom paper work, so I learned how paper was made," said Woolfitt. "I knew the size of the paper machines; I knew how we'd do the splitting; I knew our sheet sizes; I knew the grain direction; I knew the water it was made with -- I knew everything about it." In the early days when he was still teaching, he sold to his students and fellow artists as well as to other colleges. As Woolfitt's mulitplied its loyal and relatively sophisticated clientele base, so too its inventory grew, with a concentration on higher-end products. A quick trawling of Yelp reviews yields the payoff of such devotions, even decades later. One customer wrote: "I came here on the prowl for construction paper in 30 different gradients of orange, and Woolfitt's rose to the occasion, and then some."

Woolfitt also visited paint manufacturers around the globe, including in the same European countries where he scored pulp as well as in New York State. "I learned how pigment was mixed," he said of those hands-on pilgrimages. "How paints are dispersed has a big effect on how people can use them," he mused. "I sold what I knew as a painter, and if I didn't know, I could find out."

As Woolfitt expanded into distribution, the same product mastery that served him in retail proved catnip to his international clients. "If you can go into a store and tell them more about a product they sell than they do, it's pretty interesting," he grinned. Asked to share a nugget of advice for entrants in the field, Woolfitt singled out his "know-your-product" ethos. A variation on this philosophy fueled his effectiveness in the classroom. "My main concern was to teach my students how to access their perception of the world," he recalled, noting that he often used art history as a goad. "You don't have to pour knowledge into them; you have to bring it out."

Another asset that set him apart was his burning ambition. "I had lots of drive," he reminisced. He still does. These days building the modern.toronto claims much of it. Strictly a display space, the museum will show the "abstract works of living national and international artists who are underexposed in the Canadian market." (Woolfitt's own paintings have been widely exhibited -- and collected -- in Canada, among other countries.) The modern.toronto is being built on Woolfitt's Queen Street West property in the heart of Toronto downtown, on and around the hallowed turf of his earlier businesses. It's poised to open in Fall 2015.

Budgeting his time between the modern.toronto project and his art is hardly an issue. He pretty much has it down to a science. Typically Woolfitt starts his day at five-thirty in the morning and works till nine at night. Two-and-a-half hours of that stretch go toward making art. By six a.m., he's often drawing; the afternoon is when he paints. "Sometimes I wait till later in the day because I need to get ready in my head," he told me in the same breath as, "I could go right now and start to paint." For Woolfitt, there's no such thing as "waiting for the muse." He brings the same no-nonsense discipline to his studio work as he does to his business affairs.

"I believe you paint every day," said Woolfitt. "It's like washing dishes."

Photo credits:

Photo 1: Photo of Ben Woolfitt in his New York studio by Laura Blum.

Photo 2: Photo of the modern.toronto courtesy of Ben Woolfitt.

Photo 3: Untitled 78 x 72", acrylic on canvas, 2013. Photo courtesy of Ben Woolfitt.

Photo 4: Photo of Ben Woolfitt in his New York studio by Laura Blum.

Photo 5: "S-Saga," acrylic on canvas, 19.5 x 48", 1969. Photo courtesy of Ben Woolfitt.

Photo 6: "Number Two," enamel on rice paper, 25 x 37", 1971. Photo courtesy of Ben Woolfitt.

Photo 7: "Untitled" (Green Diamond), acrylic on canvas, 72 x 144", 1975. Photo courtesy of Ben Woolfitt.

Photo 8: "Number 3," etching on paper, 30 x 22",1981. Photo courtesy of Ben Woolfitt.

Photo 9: "This morning I feel very reserved." Mixed media, 14 x 22". Photo courtesy of Ben Woolfitt.

Photo 10: "Finding her at long last to assuage my despair..." Mixed media, 14 x 22", 2006. Photo courtesy of Ben Woolfitt.

Photo 11: "In the darkness of the light." Mixed media, 14 x 22", 2006. Photo courtesy of Ben Woolfitt.

Photo 12: "Quest," Water Series, acrylic on canvas, 72 x 60", 2003. Photo courtesy of Ben Woolfitt.

Photo 13: "Forever Blue," Oceanic Series, acrylic on canvas, 72 x 60", 2003. Photo courtesy of Ben Woolfitt.

Photo 14: "Untitled," acrylic on canvas, 60 x 72", 2013.