Director Hany Abu-Assad Explores Love Among the Ruins of "Omar"

If you cued Hany Abu-Assad's 2005 suicide bomber saga Paradise Now back-to-back with his 2002 marriage drama Rana's Wedding, you might get a sense of the occupied Palestinian world of his latest feature, Omar. But little could prepare you for the Shakespearean complexity of this propulsive romantic thriller that snared a Jury Prize at Cannes and, like Paradise Now, was in the running for a foreign-language Oscar.

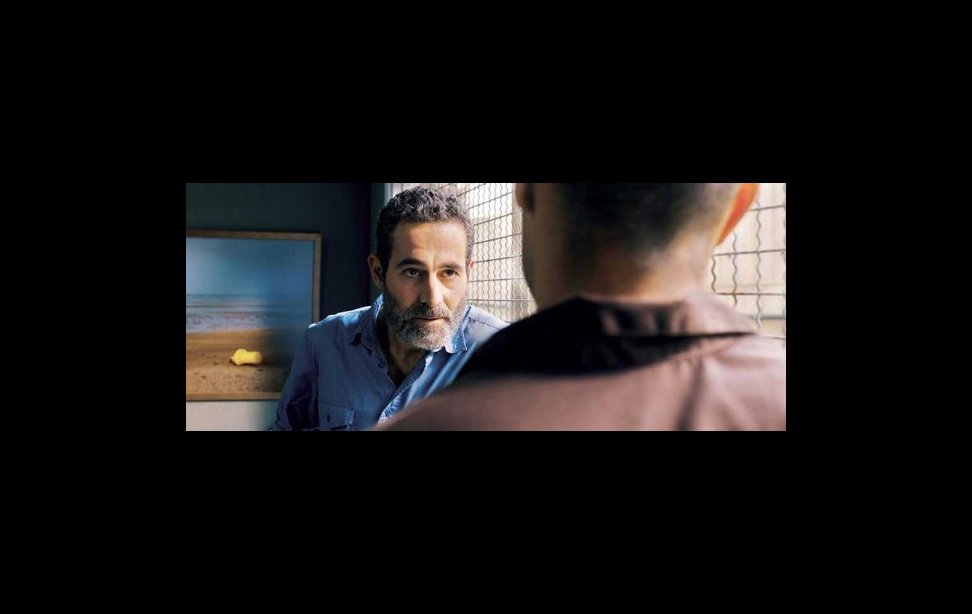

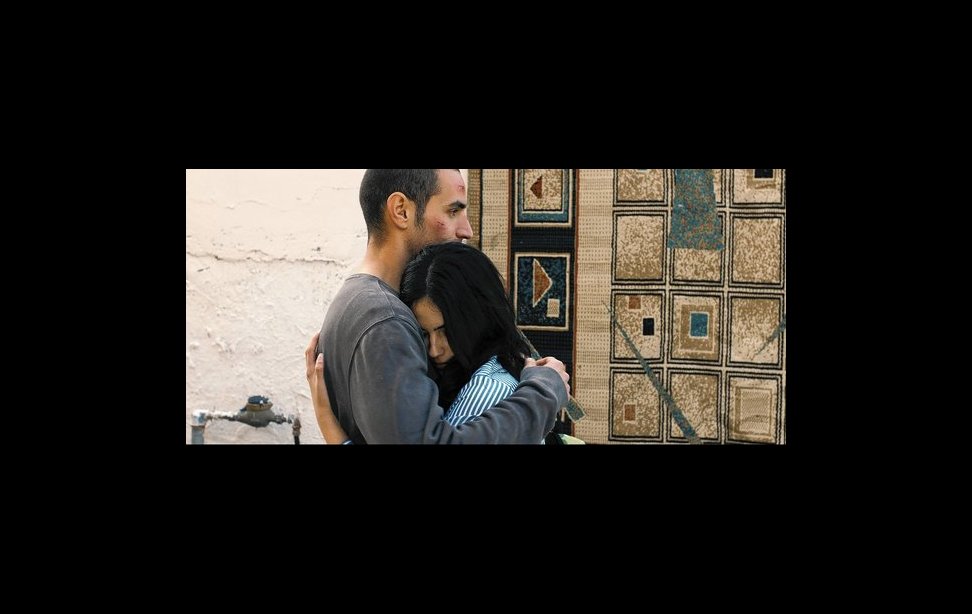

Omar does for its title character (Adam Bakri) and his beloved Nadia (Leem Lubany) what Romeo and Juliet did for its star-crossed lovers: it explores love in a climate of conflict, fear and mistrust, swapping 16th-century Verona for today's West Bank. Yet the politics of moral decay fouls up all relationships, so the tragedy also plays out among Omar and his two best friends, Nadia's older brother Tareq (Eyad Hourani) and Amjad (Samer Bisharat). To establish their bona fides as men, the three 20-somethings mount an operation to kill an Israeli soldier. Omar is captured and tortured in an Israeli jail, where he learns that he can expect 90 years behind bars and never again to see Nadia. Rami, the Israeli handling his case (Waleed F. Zuaiter) floats an option: in exchange for his freedom, he must serve as an informant. Hereon every choice Omar makes is fraught with drama (as seen in photos 1 - 3).

Coming off of his Hollywood thriller The Courier, Abu-Assad was keyed to the vitality required for a mixed mainstream audience. But for independently produced Omar he took pains to vest his characters with the depth and realness to ensure local resonance, a strategy that has fetched up international fans.

The much-garlanded director got his start in documentary filmmaking before delving into fiction, and then mixed the two forms in his 2003 hybrid Ford Transit. Omar has its own share of non-fiction elements, from the informant motif conflating real collaborators' stories to the explosive ending taken from a newspaper article, and their filmic expression through verité lighting.

The setting also blurs borders. Abu-Assad's stint in Los Angeles following nearly three decades in the Netherlands left him homesick for his native Nazareth, where he's now living and working. The so-called "Arab capital of Israel" also functions as a location for Omar, meshing with Jerusalem, Nablus, Al-Faraa refugee camp and Bisan to portray the wall-carved West Bank.

Amid a renaissance of Middle Eastern cinema, the film is unusually affecting. Almost every minute of it pulses with the menace that virtually anything could happen, and that there's no guessing who's behind it or why. The only constant is the shifting dramatic tension as each faceted character comes under suspicion. One of the achievements of Omar is that it succeeds as a work of heart-pounding entertainment no less than as a work of social art and protest.

With the film's noirish pace and themes, it's hard to imagine that the director put his largely non-professional cast through as many as 45 set-ups a day, for 41 days. thalo.com spoke with Abu-Assad about the craft and concept behind his controversial production made with an all-Palestinian crew and nearly entirely with Palestinian funds.

thalo: The opening shot of Omar is of two facades: one human and one concrete, both stubborn yet also vulnerable. How do these images comment on Omar, on Palestinian life and on the larger political impasse?

Hany Abu-Assad: It's a love story, and every love story has an obstacle. In Romeo and Juliet the families were fighting. In Omar the outside obstacle is the occupation. Usually I hate the wall but for a second I was happy with it because I realized it would serve my story enormously. I couldn't imagine a better visualization of the emotional obstacle separating one from the other. Because the wall is also a reality, you are catching two birds with one stone when in the background you tell the story of Palestinians but meanwhile you are telling a story of separation between two lovers.

th: In Hebrew the divide is called a "Separation Fence," whereas the Arabic terminology is "Isolation Wall." Was it your intention not to clarify what the wall separated or isolated?

HA: The Palestinians could recognize Nablus and Nazareth, but they didn't ask where the film fully took place. The wall separates virtually every city, every village, every refugee camp. Omar takes place in a virtual Palestinian city where the wall divides everything. The media makes you think the wall is separating Israel from the West Bank, but in reality it is separating the Palestinian community from itself. Eighty percent of the wall was built inside the West Bank. But for the story, it's just about the dangerous obstacle that Omar has to climb in order to see his lover.

th: How did the noirish stylings help you tell this amorous tale?

HA: It's a love story in a thriller genre. Mostly, in the dynamic of thrillers, the tension you get is through story and plot. But in French cinema, in films like (Jean-Pierre Melville's) Le Cercle Rouge and Le Samouraï, the tension comes from the extreme close-ups and wide shots. In this case the extreme close-up is of Omar as stubborn and vulnerable and the wide shot is the wall he's living in, and you get this tension just by cinema language rather than by plot.

th: At the press conference for the New York Film Festival, where Omar had its U.S. premiere, you talked about a third tradition as well. How did the convention of the Egyptian thriller find its way into Omar?

HA: The Egyptians made thrillers, especially in the 50s, where the tension came from humans. You don't see humans in American thrillers. The Hollywood thriller genre is very serious because they are scared to do jokes and break the tension. But the Egyptians were very good at relieving tension with a joke, comic relief, and then getting it back with a new immediacy. (Henry Barakat's) A Man in Our House (Fi baitina rajul) is a good example of the humanity and humor in Egyptian thrillers. So I thought: what if I use the dynamic of the American thriller, the aesthetic of the French and the humanity of the Egyptian and put it together in Omar?

th: What especially resonated with you about the cinematic vocabulary in the films of Melville, who was a member of the French resistance during WWII, and in Barakat's A Man in Our House, which follows a Egyptian member of the resistance to British occupation in that country in the 1940's?

HA: I feel part of a resistance. When you feel responsible to do something you will have a certain language, whether in Egypt or France or wherever, because you have this character. It's no coincidence that Melville is from the resistance and is influenced by a particular language.

th: An atmosphere of paranoia hovers over Omar. How did your own brush with paranoia inspire it?

HA: After Paradise Now I was offered a lot of projects but had the "Barton Fink" phenomenon. Most of the stories were artificial, constructed just to entertain. I discovered that my writer's block was because nothing came from real life and I felt I needed to tell a story that I really cared about. I started to dig in my memory and I asked myself an honest question, "Which story have you lived in the last few years that you really want to tell?" And it was the story of Paradise Now.

When I was filming it I became very paranoid, just like Omar. The army arrived at every day's shoot. I had no idea who was the traitor in the crew who was giving information to the army. On the other hand, the army is supposed to arrive everywhere; maybe there was no traitor. But just the idea that there is a traitor inside your crew makes you insane. You start to sleep in different hotel rooms. You don't move around with a mobile device because you think maybe it's the mobile who's your traitor and they're trying through the mobile. You start to believe the unbelievable. I felt I needed to talk about it. How could I make this subject of paranoia for a bigger audience? I felt that love is the best vehicle to talk about paranoia because we all recognize this idea that when you don't trust your lover, you start to suspect her at any move she does.

th: In what way did Omar touch off a debate about paranoia in Palestinian society?

HA: In Palestinian society we recognize this feeling where you don't trust anybody anymore. The ruling power can turn anybody into a traitor because they have the means. They speak openly about it as a strategy to foster restraint. Any pressure -- not necessarily physical pressure -- can make someone a traitor out of fear of being betrayed. Even me, I think there's the potential to make me a traitor. One of the ways to do this is through collaborators, not always to use them for information, but to let the society feel like, "We can plan a collaborator everywhere; we can turn you into traitors." It's not just destroying the resistance, but destroying human beings from the inside. Meanwhile, nobody talks about it, and I think the movie helped us in understanding that you believe the unbelievable when you become paranoid. After the movie came out a lot of people came to me and said, "Wow, so many people have lived this situtation, more than you think."

th: Early on, when the Israeli soldier asks for Omar's ID, he says in Arabic, huwiyah -- "identity" or "essence" -- not bitaqat huwiyah, or "identity card." Also early on we hear Omar and his friends joke about a cigarette pack warning with the punch line that they'd prefer cancer over impotence. Were you inviting us to consider: what kind of man is Omar and what the essence of manhood?

HA: The main theme of Omar is trust. Every scene tells the audience something about trust. When you know who Omar is, you can trust him -- or not. Trust is very crucial to identity. The joke of the cigarettes is also about trust. Your sexual performance is telling you who you are more than the cancer you are getting. It's about your trust for self; you trust yourself more by your manhood than by your sickness. Every scene is about trust, whether through identity or relationship or love or friendship or anything else.

th: Were the names a bit ironic as well? For example, in Arabic amjad means "the most glorious, or "the most exultant," though Amjad is the least glorious or exultant character; and omar means "long-living," even though we know he's not for long in this world. Tareq means "one who strikes," whereas he wasn't the sniper.

HA: Yes. Omar, Tareq and Amjad are the archetypes of war or conflict. Any war will be started by the adventurer, like Tareq ibn Ziyad -- who (led the 8th-century Islamic conquest of) Spain. The one who will fight or die for it is the soldier, Omar. And the one who will earn the glory is the opportunist, Amjad. All of the names are saying something contrary to their meanings.

th: What's at stake in this game of contrasts?

HA: Either you win or you die! Omar is the one who fought all the time to find a middle way. He tries not to become bad, but also not to become good at staying in jail, because this is also wrong. Omar constantly tries to find a balance between two impossible situations. The moment he will be forced to make a choice he will die. He wants to be the moderate, on the side of justice, but you can't be all the time on the side of justice. You have to make a choice. And the moment you make a choice you die.

th: Is that why climbing the wall is such a Sisyphusian task for him towards the end?

HA: Yes, he knows this is his end.

th: Cinematographer Ehab Assal's visuals often catch a glint of sun on a character's face and plays it off the shadows. Is this high contrast meant to match their emotions, and was that also why you mostly avoided a postcard-perfect Middle Eastern sky?

HA: High contrast will give a better expression of emotions. There was a development in the sky. In the beginning it was more blue and it slowly filled with more grey in order to subconsciously give the feel of a development. We tried to use natural light, also to give the feeling that you're not looking at a movie but at a documentary.

So the design of the light was natural, like a documentary. But the design of the picture -- the frame, the choice of movement, the color, the position -- was carefully constructed. The camera work was not documentary style. It's more dolly shots, Steadycam, everything was like a picture. The combination of fictional design and documentary light gave it this feeling that you are on the border of things. You feel all the time that you have to maintain a balance -- exactly what Omar is trying to do, actually: not to become a collaborator but also not to end up in jail. This balance is very delicate, the same as what he tried in the picture.

th: How did you and Assal create the sensation that we were there with Omar, practically in the camera?

HA: I call this the eyeline effect: the connection between the camera and the actor's eye that lets your audience maximally connect with your character. We were always telling the actors, "You have to look here when you're talking." Sometimes just one centimeter can make a huge difference between the connection of the actor with audience and the camera, just by creating a different angle. Sometimes we were giving the actors just one small change, but this change maximilized the effect that you are with the actor -- you are him almost. And this is why you feel all the time as if you are there looking to the actor looking to you. The eyeline is the secret of cinema. It can sometimes be so delicate that you have to constantly search in each scene where you can feel the actor the most.

th: When Omar is running in the narrow alleyways, we feel hostage to his entrapment, as if in a maze. By contrast scenes in the open range take on the air of a Western (as seen in photos 4 & 5). Were you intentionally alluding to this tradition?

HA: The Western is the tradition of one small man against huge nature such as the dessert -- or an enormous challenge. This is why we felt like it was a good language for us, because it was Omar against the Wild West, where the occupation is the Wild West. He has to survive alone in this harsh environment. He almost loses everything. The Western is the ultimate language of the lonely man against a big challenge.

th: Towards the end of the movie, in the scene of Omar eating with his family, were you consciously borrowing from the Christian iconography of Leonardo da Vinci's The Last Supper?

HA: Yes. In the first supper shot, he is eating, but he is connected with his family. The second time, after Tareq dies, his family is all around him, but he is not connected any more. He is messed up. He is so isolated in the middle. The Last Supper reference was more clear the second time around.

th: Rana's Wedding concludes with a poem by Mahmud Darwish about "nuturing hope." One of the billboards featured in Omar champions "planting hope" and "social responsibility." What were you conveying about the self versus the collective, and are you hopeful about the future?

HA: I am a filmmaker, but also I feel responsible, not just towards Palestinians, but to my environment wherever I am. For example, I feel responsible towards consumer society and how can we save the environment. But towards the Palestinians, because I am Palestinian, my job is to nurture hope even if at times it seems ridiculous. The billboard was green-screened in this scene. The idea was to create tension between the character's duty and desire. Omar desires the future hope of the billboard, but the reality is very slanted. I felt it was kind of ironic that we try to plant hope while the reality is bad. But I don't believe in an endless occupation and I don't believe in endless injustice. It doesn't exist in human history . (6)

Photo Credits

Photo 1: A terrorist act is hatched between Omar (Adam Bakri) and his two closest friends in a scene from Hany Abu-Assad’s new Academy Award® nominated thriller, “Omar.” Photo courtesy of Adopt Films.

Photo 2: Rami (Waleed F. Zuaiter), an Israeli intelligence operative, makes a deal to free Omar from a long prison sentence in exchange for becoming a double agent in a scene from Hany Abu-Assad’s Academy Award® nominated thriller, “Omar." Photo courtesy of Adopt Films.

Photo 3: Having just been released from prison Omar (Adam Bakri) comforts his young seamstress girlfriend Nadia (Leem Lubany) in a scene from "Omar" by Hany Abu-Assad. Photo courtesy of Adopt Films.

Photo 4: Omar (Adam Bakri) is on the run from Israeli agents who are pursuing the Palestinian murderer of an Israeli soldier in a scene from Hany Abu-Assad’s Academy Award® nominated thriller, “Omar." Photo courtesy of Adopt Films.

Photo 5: A pay phone is the only means Omar (Adam Bakri) has of communicating with the Israeli agent who is either manipulating or blackmailing him in a scene from Hany Abu-Assad’s Academy Award® nominated thriller, “Omar.” Photo courtesy of Adopt Films.

Photo 6: Photo of "Omar" director Hany Abu-Assad, courtesy of Adopt Films.