Artist Peter Benedetti's Creation by Destruction and Success Through Failure

An artist’s message can often be defined by what he chooses to complete as well as what he decides to omit or abandon

NEW YORK, NY – Painter and digital artist Peter Benedetti explains the difficulties inherent in the methods for developing and presenting ideas, ceasing work and when to cast them aside for other visions.

thalo: Although your talents spread across many disciplines, what draws you to digital art specifically? How were you first drawn into using it as a means of expression?

Peter Benedetti: Well, I graduated college with a Fine Arts degree and shortly after started working in print. Although I knew next to nothing about graphic design software at that point, I knew I had to start a career in the arts any way that I could. Once introduced to Photoshop and Illustrator, I was hooked. I lived and breathed it. Any free time I had was spent on the Mac reading tutorials and teaching myself anything and everything I could. The more I learned about the capabilities of the software, the more I wanted to know. What still amazes me to this day is that there’s literally a thousand ways to do any one thing. The tools and options available are endless. It’s like being in a studio with every type of paint and drawing tool known to man.

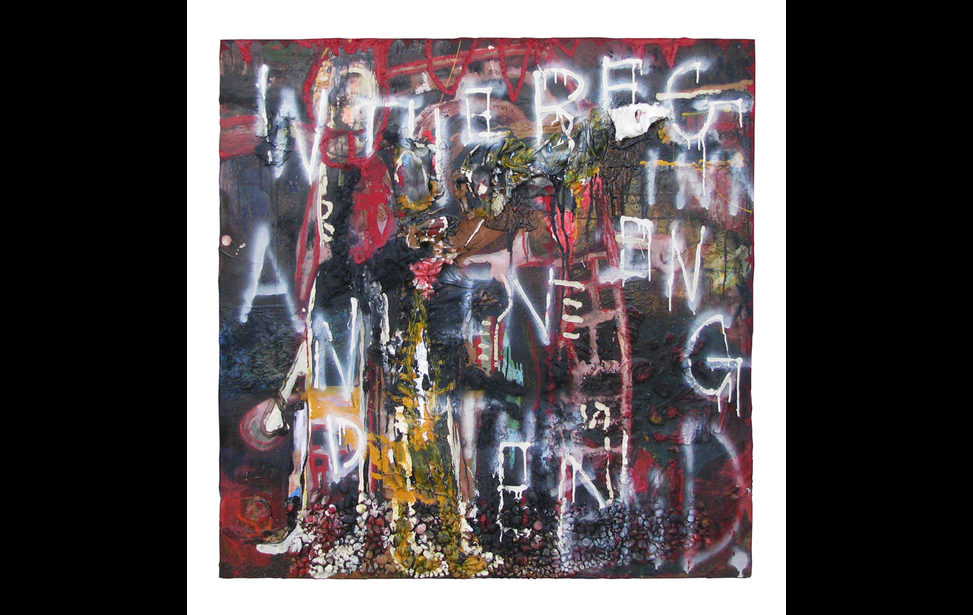

th: Both your digital art (as seen in photos 1 – 5) and paintings (as seen in photo 6 – 10) often contain a great deal of detail that often bombard the viewer with layered images. How do you know when you’re finished saying whatever it is you’re trying to say?

PB: This is the hardest thing an artist has to do. I mean, sometimes you just know, and other times it’s crippling. Deciding when something is finished is a chore that never seems to get any easier with time or experience. Very often I spend more time staring and contemplating than I do working. I still don’t fully understand how this works. But you just know whether or not you are able to move on to the next project without looking back. In some cases you have to put a work aside for weeks, months and in some cases years before you come to grips with how you must proceed. Often times this requires either destroying the work completely, or transforming it into something altogether different. Both methods can be equally cathartic. There’s something liberating about being able to destroy something you’ve worked with for hours upon hours. These are the moments when you learn the most about yourself. Allowing yourself to fail often leaves room for something to develop that you never thought possible. It can open a door that will consume you and transform the direction of your work. As far as me knowing when I’m finished saying what I’m trying to say-- I always know what I’m trying to say, I just realize that the viewer always brings something entirely different to the work, so it becomes pointless for me to ponder the question. As long as I know what’s there, the viewer can do whatever they want with it once it’s released into the world.

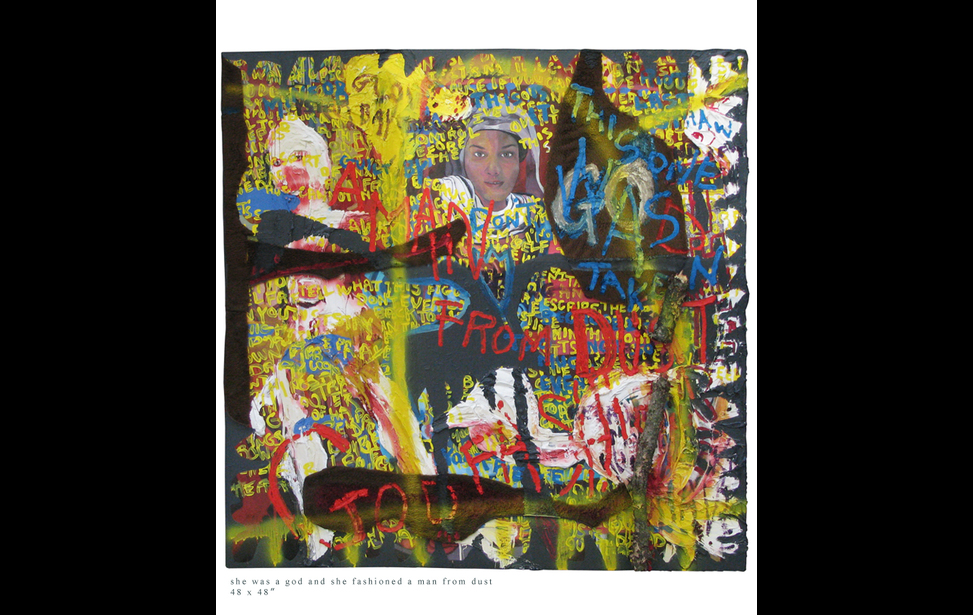

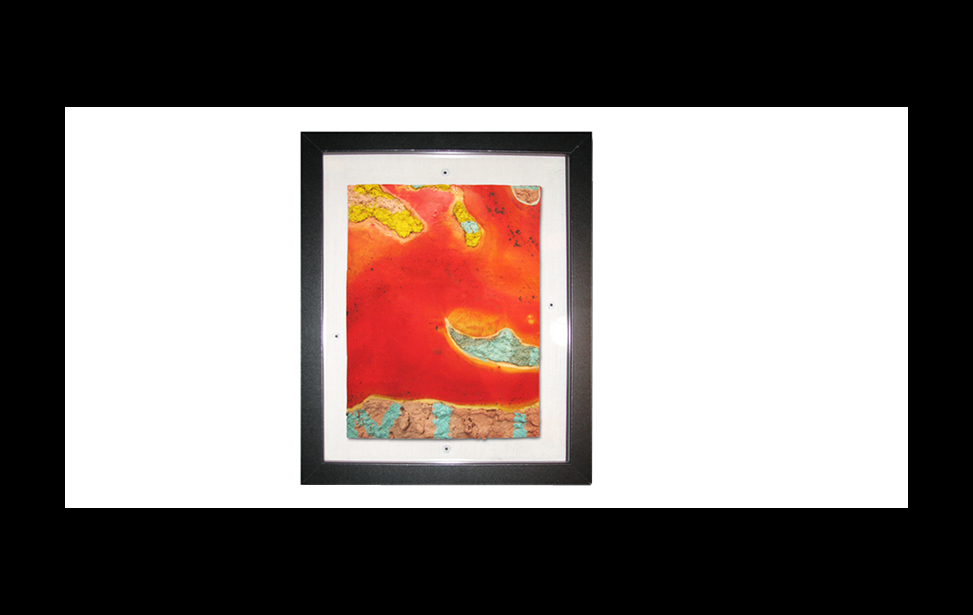

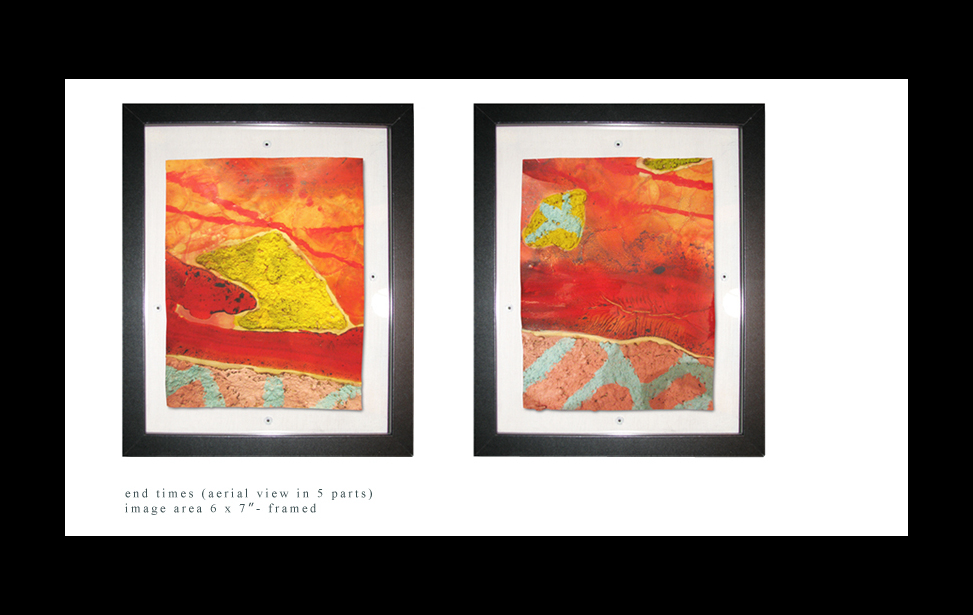

th: Many of your pieces (such as End Times [Aerial View in 5 Parts] as seen in photos 11 – 13), or She Was A God and She Fashioned a Man from Dust as seen in photo 7) have engaging and thought-provoking names. How do you decide on your titles and what (if anything) do you hope the titles achieve for your audience?

PB: My hope is that these titles evoke ideas without compromising the individual’s personal response to the work. In many ways the viewer’s response completes the work, so my concern is not to sway them in any one direction when it comes to provoking thought. How these titles come to be is never the same from piece to piece. In some cases the titles are born as the idea is developed and before the execution of the piece begins. Other times the titles are chosen as the work evolves. I’ve been known to jot down working titles on the backs of paintings as I work on them. As the newer and more potential titles come to me, I cross off older ones that become less relevant. Some of the longer titles that you’ve mentioned have very specific meanings. For example, She Was A God and She Fashioned a Man from Dust addresses a perceived relationship paradigm that exists between a man and a woman. It’s about the role of a subservient individual within a relationship. In this particular case the subservient one being the man in the form of dust, while the woman assumes the role of a God. A title such as End Times (Aerial View in 5 parts) is something slightly less visceral and somewhat self-evident. These were experimental works whereas the title came about after their completion. The paintings reminded me of something you might see out of a plane window. Vague looking maps that resembled lava covered earth. The title in this case brought to the work a necessary reference point that the paintings seem to lack without it.

th: Speaking of text, how has graffiti and urban aft influenced your work?

PB: Graffiti is one art form among many that I admire a great deal. I love the rebellious aspect involved in the culture. I especially love the sarcastic and politically driven work of some of the more modern graffiti artists working today. When I see random tags in odd places I often wonder to myself about the history involved with that piece of art. Simple things like, “How long has it been there, and at what time of the day was it created?” I also wonder about the background of the individual who created it, and what drove him or her to choose this particular location. It’s almost like deciphering clues and creating a back story of your own. As far as how this relates to my work—I’ve always found beauty in the simplest tags. For a while I was making these dark highly textures pieces with random white text written across them. Much of what I’ve been trying to do in some of these abstract pictures is to illustrate simplistic or otherwise unrecognized beauty that might be seen in an urban setting. These are in many ways my version of a graffiti tag or what I might call “framed” vandalism. I want these paintings to evoke that kind of feeling. I want the viewer to attempt to decipher a story from what they see. I want them to see the painting and then go out into the world with a better appreciation of something random they might see on the street. It’s all about presenting a perspective that a person might have otherwise missed.

th: There often seems to be an cathartic and violent undertone to many of your pieces (digital and paint-based). Is anger your key artistic motivation, or am I projecting this assumption where it doesn’t belong?

PB: I hear this a lot. I understand the perceived projection, but I don’t always agree with it. I would never deny that some things appear to come from violent places, but it doesn’t always mean it’s coming from a violent person. Anger is a fact of life and it’s a part of everything, but it’s just one part. I believe that ideas reside in what you might call “pools of thought.” Whatever pool I decide to draw from, the final result is always intended to reveal a unique form of stylized beauty. How we define or interpret content can be very subjective. Something as simple as color scheme can provoke certain perceptions and projections. There’s a reason we sometimes gravitate toward ‘darker’ content. There’s a certain kind of wistfulness involved. Decay is natural and beautiful. An abandoned building might be the most inspiring thing you’ll see in the course of a day. It’s a catalyst for ideas. If anything, the act of illustrating these ideas relieves an inner violence that is indeed cathartic.

th: You recently worked on Marchen, a book containing your digital illustrations for a story and accompanying CD by the band Umbrella Brigade. What were the biggest challenges you faced in working on that project?

PB: I would describe the project as a challenging success. In many respects it was unlike anything I had done in the past. I was collaborating with a group of musicians who already had deep personal connections to the work I was attempting to illustrate. Having an underlying mutual respect for the artists you’re working with is extremely important. Marchen ‘the story’ was written by Whitey Sterling, who happens to be a brilliant songwriter and lyricist. I read his story several times while formulating my ideas for the illustrations. I wrote notes about my interpretations of the text and shared my ideas with Whitey. I provided him with updates throughout the illustrative process, and he would provide me feedback along with his own personal perspective pertaining to direction. Marchen provided me with a unique perspective on collaboration, and made me realize how important it is as an artist to occasionally break out of your own creative comfort zone. You’d be surprised what you learn about yourself and your own art while working with others. I can go on and on about the brilliance of the accompanying music, but I’ll leave that to the listener to discover on their own.

All photos courtesy of Peter Benedetti.