"Peggy Guggenheim - Art Addict": A Conversation with Director Lisa Immordino Vreeland

By Laura Blum

Peggy Guggenheim - Art Addict is directed by Lisa Immordino Vreeland, who has a flair for baring the eccentricities of women tastemakers. Her previous film, Diana Vreeland: The Eye Has to Travel, did just that for her grandmother-in-law, the famed editrix of Harper's Bazaar and Vogue. Whereas Vreeland blazed trails in the art of fashion, Guggenheim achieved her pioneering in the fashion of art. Yet both high priestesses of culture reinvented themselves -- and modern aesthetics -- and both of their lives connected the defining dots of the 20th-century. Now, with Peggy Guggenheim, Immordino Vreeland traces the terrain of her new subject with the ease of someone who has previously treaded nearby (as seen in photo 1).

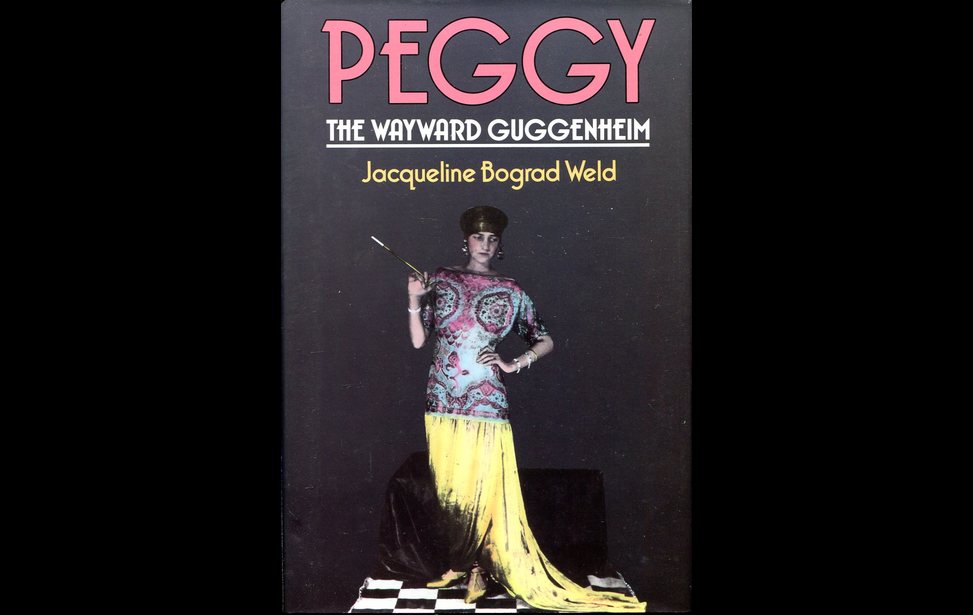

She also got a lucky push from a recorded interview with Guggenheim that turned up during production. Never before released, it was conducted by Jacqueline Bograd Weld for her biography Peggy: The Wayward Guggenheim and left to languish in the author's basement (as seen in photo 2). Until Immordino Vreeland showed up. The film's style and tone take a page from the spirit of Guggenheim's crackling confessional in this final interview that she gave prior to her death in 1979 at age 81. Together with a gleamy array of talking heads, art images and archival footage, the audio backbone provides intriguing insights into the woman of many appetites at the center of Immordino Vreeland's pacy work.

Peggy Guggenheim's reputation precedes Peggy Guggenheim. The "Mistress of Modernism," it's often gossiped, had slept with nearly 1,000 people -- including many of the artists she supported -- though she herself put the headcount in the hundreds. (Her husbands, Laurence Vail and Max Ernst, were also artists.) A less tasteful filmmaker might have buttered together tubloads of sex and art, but Immordino Vreeland seems to have determined that more could be done with Guggenheim's high-profile relationships than revealing their seemier sides. Still, recognizing the vast prurient interest generated by her naughty subject, first and foremost for that subject, herself, Immordino Vreeland makes hay of Guggenheim's mating patterns. "Sex and art absolutely went hand in hand in her brain," comments Picasso biographer John Richardson in the documentary. Guggenheim herself reflects, "I think I was always lonely," followed by the pathos-tinged punch line, "I guess I was sort of a nymphomaniac."

Whatever else the "black sheep" of the Guggenheim family may have been intimately acquainted with, she evidently knew from emotional pain. She was 13 when her father went down with the Titanic (though as everyone knew, his accompanying mistress survived), and her mother was supposedly daft. "Wouldn't you think this constant sleeping around was a little bit a desire to replace the father she lost at a young age?" Immordino Vreeland mused with thalo.com at the Tribeca Film Festival, where the movie premiered (as seen in photo 3).

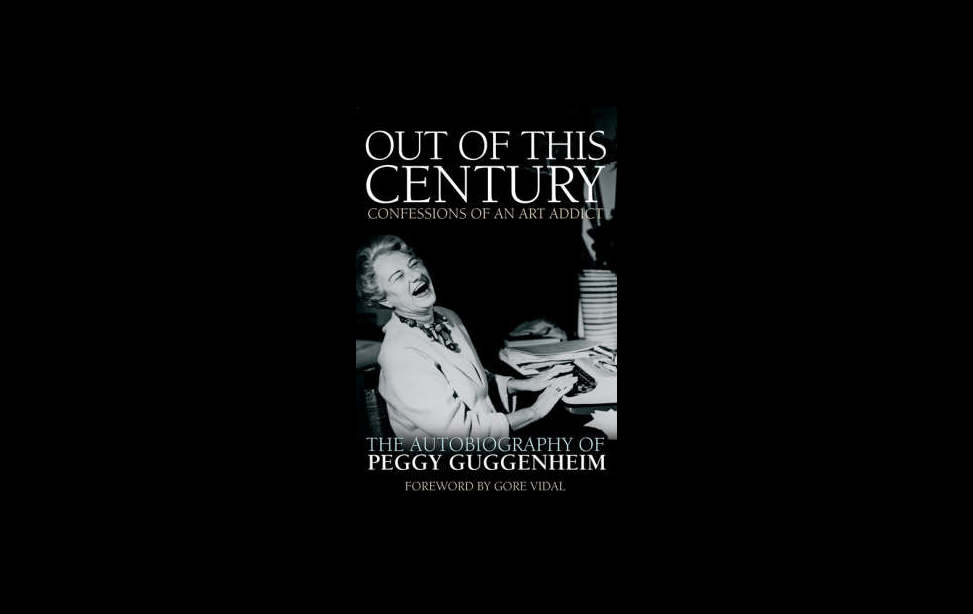

The former Art History major said that she wrestled with how much to include about Guggeneheim's dalliances. Mostly she took the cue from Guggenheim. "She was the first person to talk about her affairs," noted Immordino Vreeland. "It's part of her character and it's part of her story. It was so courageous (to write her autobiography, Out of This Century: Confessions of an Art Addict) (as seen in photo 4). That for me is being a feminist," she said. "Also, look whom she's sleeping with... Every shot you see of Marcel Duchamp! Yves Tanguy! Samuel Beckett!

One humid vignette narrated by Guggenheim involves that very Irish writer, whom the expat heiress met in the late 30s at a soirée hosted by James Joyce and who escorted her home. Guggenheim remembers the four-day romp that ensued, during which she and Beckett "only separated for sandwiches" from room service. Curiously, Immordino Vreeland leaves out the juciest part of the affair: that Beckett allegedly convinced her to focus exclusively on modern art. Asked about this omission, Immordino Vreeland argued that Guggenheim had already chosen her direction and that Beckett's role was merely supportive. Additionally, the filmmaker said, he was hardly the sole voice whispering sweet modern art nothings in Guggenheim's ear.

Duchamp, as the film highlights, was a key figure in Guggenheim's decisionmaking all around. "He taught me everything about modern art that I know today," Guggenheim coos. "He taught me the difference between Surrealism and Abstract Art; he arranged all of my exhibitions...a great, great teacher." It was with Duchamp that Solomon Guggenheim's niece launched her first exhibition space, Guggenheim Jeune, which was a modern art gallery in London. Duchamp notwithstanding, René Magritte in an audio recording credits Guggenheim with having had a "major influence" on modern art's acceptance in England.

Just what her contribution was, whether in the UK or across the Channel, the Atlantic or the world, is a matter of opinion. Where does Immordino Vreeland come down on this question? Read on to dive deeper into her documentary, her discoveries and how the passions of Peggy Guggenheim live on.

thalo: In your documentary, Guggenheim is variously described as a genius and a game changer, but also as "a bridge character," "a narcissist" and "her own greatest creation." John Richardson says Guggenheim "did remarkably for someone who had no innate taste or flair for things but who had a passion to use art to promote herself into a personality, to a star..." Which viewpoint do you most agree with?

Lisa Immordino Vreeland: John Richardson also used this word "pollinator," which I think is really fascinating. There's no doubt that she was in the right place at the right time, though you can be in the right place at the right time, but not have the right personality to take things in. She had a sense of openness and understanding. Once she decided what she wanted to do -- and this was not at a young age, it was at 40 -- she took it on full blast. She didn't do it by herself; she had these wonderful advisors. But she was smart enough to pick Marcel Duchamp as her first advisor and mentor and professor of modern art. She was a pollinator because she knew how to put these people together. People were attracted to her and attracted to the way that she was giving support. Was she doing this only for the goodness of Peggy? No, I don't think that she was. When Isabella Stewart Gardner started her collection, it was only for Isabella's own eyes. Peggy always wanted to build a collection to show and share with people.

th: According to Jimmy Ernst (son of Max and director of Guggenheim's The Art of This Century gallery beginning in 1942, shortly after its founding in her native Manhattan), Guggenheim first considered Jackson Pollock's work "dreadful" until Piet Mondrian tagged it "the most exciting art" he'd seen in America. Ultimately, how much credit does Guggenheim deserve for discovering, say, Pollock, and what does Ernst's anecdote say about her chops as an art impressario, who one of the film's early commentators says must have "an intuition for talent even before it's realized"?

LIV: She was in tune with her advisors then, but she did not have to support any of these artists the way she did. And she certainly did not have to give Pollock a contract. There's a story about Peggy being in bed with mono or something horrible and (Pollock's wife, the painter) Lee Krasner kept going there and bugging her -- "We need your more of your support" -- because they'd found the house in Springs. The fact is that Peggy gave them support. Maybe Jackson Pollock didn't sit down and have these intellectual conversations with her about the art. But she gave the support that they needed and she believed in them at the onset of their careers. Did she discover Jackson Pollock on her own? No, but she was open to looking at the work and to understanding what it was. And that deserves a lot of credit. There were a lot of collectors, but they understood the Gauguins and Matisses of the world.

th: In the film, Weld relays a wartime story about Guggenheim approaching Picasso at his Paris studio and being dismissed with a curt, "Madame, the lingerie is on the fifth floor." What was that about?

LIV: Peggy was doing these purchases like a supermarket shopping list. There was the insinuation that she wanted to buy a painting a day. Picasso was very elitist in those days. He was in a class of his own.

th: As we see in the section concerning 1939-41, painters were desperate to offload their works and many dealers were fleeing for their lives. Where were the (Gertrude) Steins in the collectors competition?

LIV: The Steins had amassed their main collection earlier.

th: As we learn in the film, Guggenheim especially resonated with outsider work and with the artists' bohemian lifestyles (as seen in photo 5).

LIV: That's why she felt so comfortable, because she felt that she was an outsider. If you look at whom the Steins supported, they were all well established artists. In Peggy's case, she believed in these artists who were total underdogs.

th: New Museum director Lisa Phillips remarks that Guggenheim was "an object of ridicule." Would the social heiress have secured a more hallowed name in the annals of modern art had she not been so wealthy? (as seen in photo 6)

LIV: She was a wealthy heiress but she didn't act like a wealthy heiress. Look at Isabella Gardner. She had (art connoisseur/critic Bernard) Berenson running around doing all of her dirty work. Peggy was in the trenches with the artists, looking at the work, putting herself in danger in Paris in World War II. She was there. She didn't look at it as a man's job. She looked at it as a passion, a driving desire to build something. We downplay her heiress side in the film because I think it's secondary. It's the Guggenheim name that holds a lot. She takes care of so many people. She was giving what she could away.

th: Had she been a man, do you think her art-word reputation would have commanded more respect?

LIV: Compare her to Gertrude Stein, who was a writer and who was considered a great intellect. Peggy was never considered this great intellect. Yet last weekend at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice, Pollock's newly-restored mural Alchemy was installed. The two most important examples of art in the 20th century are there together: Mural and Alchemy. About her legacy as a woman, people look at her achievements. Her legacy is originality.

th: What congruencies do you see with Vreeland?

LIV: With both of them there's the idea of jolie-laide. Both women weren't happy in their childhood and there's this sense of remaking themselves. But they're very different characters. Peggy's personal story is just really devastating. Vreeland didn't have this devastating story at all. But they were both women who made this change in their life and did it in a big way. And they left us something to look at. Peggy did not leave it in her words. It was hard for us to find material when we wanted to get her reactions to the paintings and why she loved them so much. The reason this is not in the film is because it didn't exist. But look at the examples of the paintings she chose. Her advisers were not sitting there picking the paintings. That was her eye. It gives the younger generation today a sense of empowerment. If you're not happy with what you're doing with your life, if you believe in your dream, in your passion, you can achieve these things. Now more than ever the younger generation needs something to hold onto. I feel that this is what you get if you watch Peggy's story.

th: What advice do you have for a filmmaker seeking to make a documentary covering a large sweep of history and material?

LIV: In this film the biggest challenge was the amount of material. There was so much of Peggy's personal history along with her achievements that the issue was getting a sense of what to cover. You start to cut back and you try to say: this is important; this isn't important.

th: What's an example of something you jettisoned?

LIV: In The Art of This Century gallery, she has so many important shows. She gave the first collage show in America, and that's where Motherwell started his collage. It was in the film and then we took it out. Those bits that art historically I may love -- gone! -- but but fortunately we're making a film and we have to tell her story as well. Especially with today's audience. You have to have a lot of personal information because people are really interested in that. And that's what drove her character and really made her want to change herself.

th: What guided your decision to include her reminiscence of her affair with Pollock when Krasner was away? Recalling that Pollack "threw his drawers out the window," Guggenheim pronounces that the tryst "was very unsuccessful," and then goes on to say, "I wouldn't put that in my book for anything in the world."

LIV: These tapes are for someone who's writing her biography. So if she didn't want to say it, she shouldn't have said it. And the fact that she talks so openly about the sex is because this is the true character of this woman, and this is not what formed her. First of all, everyone else was doing the same thing. And you do not walk out of the film and say, "Oh well, she slept with a lot of people." That's not what the film is about and in no way overshadows her achievements.

th: What did you glean from the audio tapes that you may not have gotten from the written sources?

LIV: Peggy had this funny way about her tone. There's this irony. There's this little biting sense of humor. She made it all seem so easy. It was also profoundly sad. But she had this way of letting things fall off of her shoulder.

th: How did Guggenheim's life story and the art shape the way you conceived the film aesthetically?

LIV: The art acted as dream sequences throughout the film. We used it as a character to help push the story along. All of the art that we used she owned, except for a couple of pieces. She gave away Pollack's mural, but she had commissioned it, and then there were the paintings by (Robert De Niro's parents) Virginia Admiral and Robert De Niro senior, which were not hers. But in telling the story of World War II, we looked to see exactly what she bought in World War II. We really stuck with the times except during those dreamy sequences where she's talking about patronage; there we could put whatever we wanted.

th: The film clips look trippy -- take Salvador Dalí's Surrealist sets for Alfred Hitchcock's Spellbound, for instance -- but the still images bear few if any editing tricks. Was the idea with the paintings to punctuate the rhythm and let the film breathe?

LIV: Frankly, we didn't let it breathe enough. It's such a dense film of information that if we had to show the artwork in a complicated way it would make it even more difficult. We tried different things. Sometimes we had close-ups. It's always hard to make a painting look non-academic onscreen. There's not that much that you can do. You could take the idea of coming in really close to a detail of a painting and coming out of it, but sometimes it's just thinking too hard and working too hard.

th: What made you want to do a documentary about Peggy Guggenheim?

LIV: I read Peggy's autobiography when I was in college. I was thinking of the Abstract Expressionists. The last year that I was promoting The Eye Has to Travel, I was researching Peggy. I wanted to make something in art. For me, making films is about the 20th century. It all goes back in New York to Peggy and The Art of This Century gallery.

Photo credits.

Photo1: A scene from "Peggy Guggenheim - Art Addict" courtesy of Submarine Entertainment.

Photo 2: Book cover art for "Peggy: The Wayward Guggenheim" courtesy of The Bodley Head.

Photo 3: "Peggy Guggenheim - Art Addict" director Lisa Immordino Vreeland. Photo of courtesy of Submarine Entertainment.

Photo 4: Book cover art for "Out of this Century: Confessions of an Art Addict courtesy of Andre Deutsch.

Photo 5: A scene from "Peggy Guggenheim - Art Addict" courtesy of Submarine Entertainment.

Photo 6: A scene from "Peggy Guggenheim - Art Addict" courtesy of Submarine Entertainment