Edible Creations: The Craft of Blown Sugar

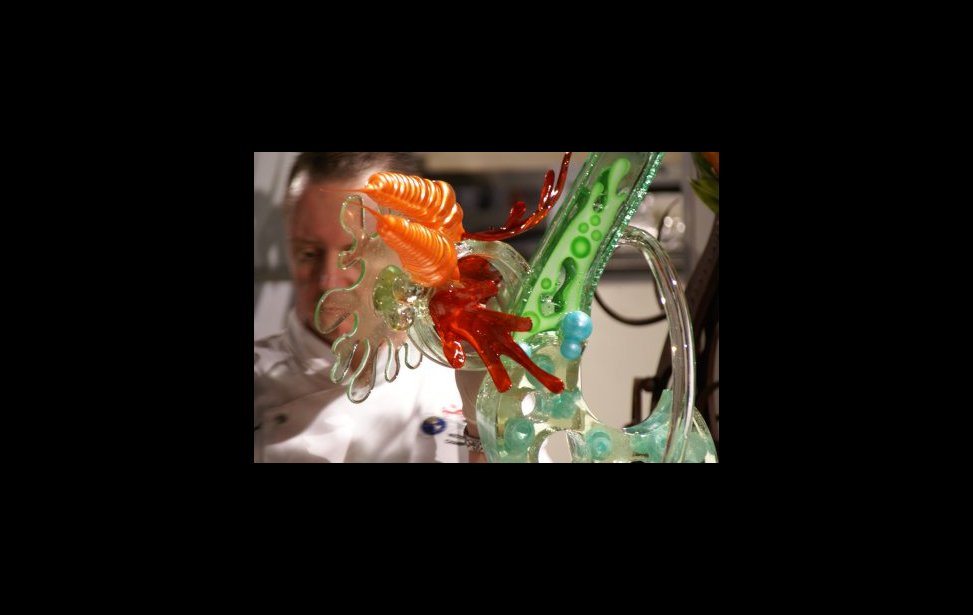

The sculptures can be blown, pulled, and cast; they can range from painstakingly delicate lines to aggressive, colorful forms; they can be transparent or completely opaque (as seen in photo 1). And they are delicious!

The craft of sugarwork begins with granulated sugar that is cooked into very hot syrup, which has incomparable shine and is so translucent that it is easily mistaken for glass (as seen in photo 2). It is then folded repeatedly into itself, until it is thick enough to be sculpted into various shapes, stretched into ribbons, or blown with a hand pump. Just like blown glass, blown sugar must be constantly rotated to retain its shape. Sugar can be blown into molds or shaped by hand, and then cooled with fans when the desired shape is obtained (as seen in photo 3).

Also called “the new spice,” “sweet salt,” “medicine,” and “white gold,” sugar was first extracted from sugarcane in Southeast Asia around 8000 BC. Though sugar art is not nearly that old, it has evolved in many different cultures over the last few centuries. During the Ottoman Empire sugar figures were featured in elaborate gardens for festivals and celebrations. Medieval European royalty is also associated with some of the most elaborate sugar sculptures that have ever been created, including a leopard grasping a fleur de lis while crouching on top of a custard tart for the 1429 coronation feast of eight-year-old Henry VI.

For those who are trained and have practiced for many years, sugar is an impressively versatile medium with a wide range of possibilities. "If you can think of an image, you can create it in sugar," says David Watson, chef instructor for baking and patisserie at the Pennsylvania Culinary Institute in Pittsburgh.

But it seems that the extreme delicacy and short lifespan of blown sugar has limited it mostly to the culinary world, where it is a prominent subject of some of the most prestigious pastry competitions in the world. Jacquay Pfeiffer, chef at the The French Pastry School in Chicago, says, “No pastry chef ever goes to art school and they actually should.” He has been working in sugar art for 36 years, but also studied glassblowing and has derived inspiration from glass artists Dale Chihuly and Lino Tagliapietra.

He has also studied with Ewald Notter (his work featured in photos 1 and 4), who is considered one of the best sugar sculptors in the world by his peers. Notter is most famous for his mastery of color and exquisite craftsmanship. He was born in Switzerland and trained at Confiserie Sprüngli in Zurich, where he first became interested in pulling and blowing sugar. Later he founded the Notter School of Pastry Arts in Orlando, Florida, where he continues to teach. In 2001 he won the gold medal with the US team at the Coupe du Monde de la Patisserie in Lyon, France, with the highest score ever recorded in sugarwork.

His work ranges from eerily representational figures to highly abstract, jewel-like cubist forms, from shaved chocolate foliage to curving arcs that defy gravity.

PHOTO CREDITS

Photo 1: Sugar Sculpture by Ewald Notter, photo courtesy Megan Osa, photographer

Photo 2: Blown sugar showpiece by Laurent Branlard, photo courtesy Chris Northmore, photographer

Photo 3: Blown sugar in wound wire, cooling with a fan, photo courtesy Chris Northmore, photographer

Photo 4: Sugar Sculpture by Ewald Notter, photos courtesy Megan Osa, photographer