“Viva” Director Paddy Breathnach Points the Limelight at Havana Drag Queens

By Laura Blum

Irish director Paddy Breathnach (I Went Down, Shrooms) gleaned the idea for his latest film Viva during a visit to Cuba 20 years ago. Now that film, a study in transformation, arrives as the socialist island country braces for inevitable change.

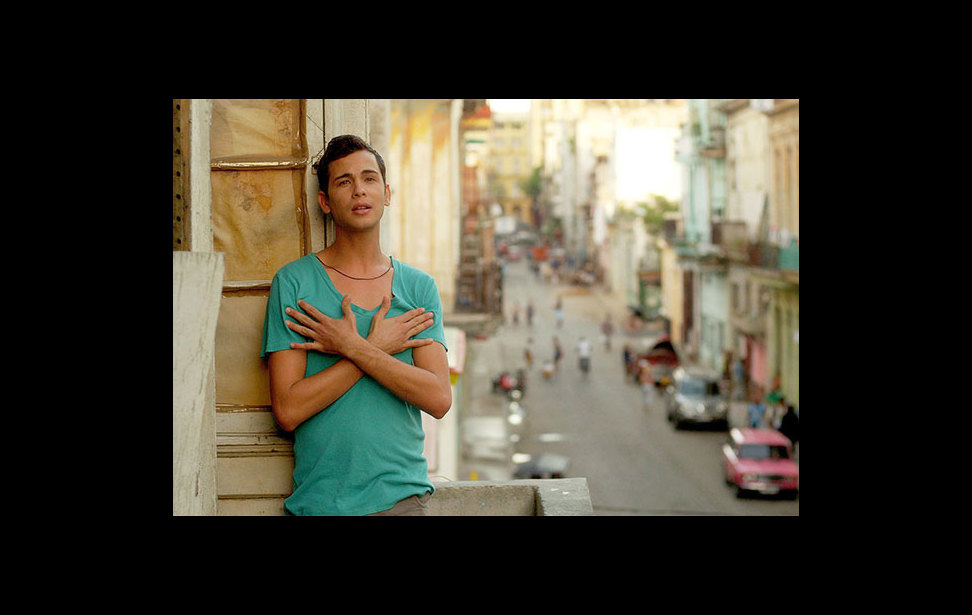

Viva follows a gay 18 year old named Jesús (Héctor Medina), who styles wigs for the drag queen joint run by Mama (Luis Alberto Garcia). Jesus himself dreams of taking the spotlight, as glam alter ego Viva. At the other end of the masculinity spectrum comes Ángel (Jorge Perugorría), a former boxing champion with traditional notions of machismo. He is Jesús’s long-absent father, and when he suddenly resurfaces after a prison term, soaked in whiskey and testosterone, there goes Viva’s dramatic calling. Yet just when it seems that Ángel is a devil and Jesús cannot be resurrected in drag, their shared desire for family connection and their dire financial straits bring them towards a climactic redemption.

Breathnach spoke with thalo.com about his Cuban saga, which was Ireland's hedge for the Best Foreign Language Film statue at the 88th Academy Awards.

thalo: The film opens with an overview of a Havana barrio, soon followed by a barbed exchange among several performers who work at Mama's drag club. How does Jésus see himself in the community and what's his take on these brash characters as he goes about his search for identity and belonging?

Paddy Breathnach: He starts the film where he doesn't have a voice. He's surrounded by people who have plenty of voice, who are large personalities in the drag club. It emphasizes his position of being on the margins. He enjoys them and is fascinated by them, particularly Mama. He sees her as someone who clearly has a voice and expresses herself with a depth of emotion. But he hasn't tried it and doesn't have the bravery to step forward. His quest is to find that identity, initially as an individual finding his voice, but as the film progresses he has to reconcile that with his place within a group, within a family.

th: In the end Jésus asserts himself without losing his tender side. By not becoming petulant like the other drag queens or scrappy like his father, how is he redefining power?

PB: He's regarded in the beginning as being weak, but through that weakness, his meekness, he is still true to himself and steadfast, and through his goodness he manages to achieve that goal of unifying two worlds. We're considering the nature of male power. As he performs that last performance and puts his hand in the air, he does a bit of a resurrection. When he comes back he is the master of his own identity, individually, and also that of the group.

th: It's hard to overlook the fact that “transformista” is one of the words for a drag artist in Cuban Spanish, and that the film takes place during a time of transformation in Cuba. How does Jésus's metamorphosis reflect the challenges facing the island as it experiences transition?

PB: There is definitely an allegory about the country. Cuba has been on the edge of change for so long. There is constantly this sense of becoming, but whether it actually fully happens is questionable. Now maybe that process is going to move forward in some way. Cuba has many problems, economically, and lots of frustration. But equally there's a real sense of civilization and sophistication, and people are very well educated and aware of the world and can articulate that in a conversation. There's also a sense of solidarity.

th: How does that social connection come through the line of dialogue, "None of us are savages yet," which grandmotherly Nita says to Jésus as she's preparing food for the ailing Angel?

PB: Cubans I talked to know that things have to change, but they also have some fear and trepidation, because the capitalism that has taken hold in the region is often a very savage capitalism. For example, in Mexico we've seen the impact of the drug lords. Whatever way Cubans move forward, they don't want that to be their path. There isn't a real drug culture there.

th: What does the film say about intergenerational change in Cuba, for instance, when Angel tells Jésus to let Cecilia and her baby live in the apartment, and when Mama bolsters Jésus at the end?

PB: There's a moment at the end when Mama takes the curtain that Jésus has thrown onto the ground and she puts it over his shoulders. It's a sense of a coronation. What it is is the transfer of power from the older generation to the younger generation. In Cuba, there's a frustration that maybe the next generation hasn't had its chance. When a close relative dies, there's that idea of the generosity between generations, where the passing generation allows the new generation to move move into that space. And equally, the younger generation allows the older generation to pass gracefully. There's a positive engagement between moving on from the past and some of the good things that it may have had, but equally there's resolution in dealing with some of the difficulties of past and how the new generation can move on.

th: How did you come to the theme of transformation in the first place?

PB: I went to a couple of shows when we were researching. It was a little clandestine at that stage; it's less so now. You'd go into a house, and you'd have to make a phone call to find out where the show was that night. Somebody would bring somebody else and eventually you'd get an address. I went one night through this house and and out into a backyard in a fairly blue-collar suburb of Havana. At the end of the yard they'd put up a red sheet on the wall, and they had one light as a spotlight. But it completely became a theater. With that simple sheet and light, it became a place where you could transcend the reality and have access to this world of dreams and possibility and connect to profound emotions. It felt very remarkable that this could be achieved out of so little. So the transformative power of art and the idea that with true artifice you can hit deeper meaning were very interesting to me.

th: How did this play out with the raw, unrefined sensibility of the production and characters?

PB: Seeing the effort involved in the transformation creates the desire to do it. When it's too perfected, you don't see that. There's a beautiful collection of photographs by a Swedish photographer, Christer Strömholm, who shows transsexuals in Paris of the 1960s. The book is called Les Amies de Place Blanche. It's not a polished look, and that's what I was very interested to achieve. I didn't want to make the drag artists as close to women as possible. I find it more beautiful to see that imperfection. The beauty comes from seeing the desire to become, to do.

th: Is this where your interest in political philosopher Herbert Marcuse comes in?

PB: When I was a student I was interested in the Frankfurt School of critical theory, which said that the revolutionary potential of art is in its beauty, is in the sensual substance. Now I'm interested in making statements, but nothing political with a capital "P."

th: One of the most moving scenes in the film is when the old drag artist Lydia belts out "Ave Maria," which Cuban-raised Maggie Carles famously dared to sing at a concert in Havana in 1989. Were you referencing that dare?

PB: It was an added thing that Maggie Carles sang it in the Karl Marx Theatre and it was a big statement at that time. But this wasn't the overriding reason for using it. I more interested in the mix of sacred and profane, where you get this very deconstructed image of a woman: it's a man dressed as a woman, but not completely finished, and there's no wig and the brassiere is loose and awkward. Lydia is singing by a toilet, yet it's this most beautiful hymn. I thought that would have a power, and in another way it's comical and ridiculous.

th: The title of another featured song, "Patria o Muerte," is what Che Guevara said as Cuba's representative to the UN in 1964. Was this also a wink to the island's political history?

PB: There's a sense of fun about this choice, but it wasn't too heavily designed. I can't claim that it was embedded from an early stage or that I was making a statement with it.

th: With such melodramatic classics as "Ojalá que no puedes" (Maggie Carles), "Es Mejor Que tu lo Sepas" (Rosita Fornes) and "Como Cualquiera," why did you choose not to translate the lyrics, and what drove your playlist?

PB: I wanted the audience to watch the performances and not worry about subtitles. In choosing the songs I was always going after a certain spirit. But the journey to get the music was very difficult because the total music budget was about 30,000 euros, and that included score. Let's say that there were a lot of songs that I wanted to get and wasn't able to. I was lucky that I ended up where I was. Because of the limitations on the budget, it forced us to choose music where the rights still resided within Cuba. That gave the music a certain authenticity and coherence because we were getting it from a certain stream.

th: How did that authenticity carry over to the cinematography, and what format and lenses did you shoot on?

PB: We shot on a RED Epic, and the lenses were superspeed lenses, which let you shoot in low light conditions and have a very beautiful quality. But they are very practical in the sense of how we set ourselves up. We were lit 360 and we could always react to the actors. I wanted to do very long takes and also to limit the amount of starting and stopping in the process. We'd often shoot a master shot and it might evolve into closeups in another take, and we might rejig that shot in numerous ways, but not have that break where everybody's energy has to rest for a while. What we did is a different way of shooting and it allows the actors to have a more fluid space to work within.

th: Is there a particular film that inspired the camerawork?

PB: The Wrestler by Darren Aronofsky was a film that I liked an awful lot, in terms of the way the camera relates to the central character, in terms of movement. There's a very connected sense between the camera and the actor. It always has a sense of unfolding destiny in front of it, whatever that relationship between the actor and the camera is. The DP and I made a lot of rules for ourselves. We used a 25 mm lens a lot. For example, there are a lot of shots where we're traveling with Jésus, but we're always behind him or sometimes to the side. But we're never in front of him until the very end of the film, where the camera moves around after he's been to his father in the morgue. For the first time we're walking in front of him as he's walking towards us. It was this sense that we're always behind him moving into his destiny, and then at this last moment we see come around to see him walking towards his destiny. It gives a sense that he's arriving at that moment.

th: How was it to work with these Cuban actors?

PB: I didn't realize how good the actors were going to be. There's a fantastic tradition of actors and training, and they're very professional. I had intended to make the film in a more documentary and naturalistic style, but when the actors came in, I felt if I did that I would be putting a lid on it. And I felt that there was a specificity and a detailing that I could get with the actors, because they were so good, that I should go to that place. So I moved away from an observational naturalism to something a little more kinetic or cinematic. When I auditioned I changed my way a little bit.

th: What else did you discover as an Irish director working in Cuba?

PB: You can't just walk down the road and buy wigs and makeup, so improvisation is something that has to be done there. We could have brought things from Ireland, but there's something about the limitations process in forming an aesthetic that I found a good thing.

th: The Irish have been looking outward since Irish monks transcribed classical civilization during Medieval times, and surely before. What drew you to Cuba?

PB: We've been vagabonds for so long. We're a small place, so while there's a rich culture there, you use it up quite quickly.

th: Let's close like the film does, with your take on Jésus getting together with his hustler friend Don and helping Cecilia to raise her baby.

PB: That last scene was a bit of an afterthought. We said, Let's have some sense of possibilities that he might have a relationship with Don. But equally, we're saying Don is still on the game. We're not saying that everything is cured. There might be some love in his life. By the way, that baby is my daughter, Josie Breathnach, then about eight months old.

Photo Credits

1) Héctor Medina as Jésus in Paddy Breathnach’s “Viva.” Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

2) (L-R) Jorge Perugorría and Héctor Medina in Paddy Breathnach’s “Viva.” Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

3) Héctor Medina as Viva in Paddy Breathnach’s “Viva.” Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

Photos courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.